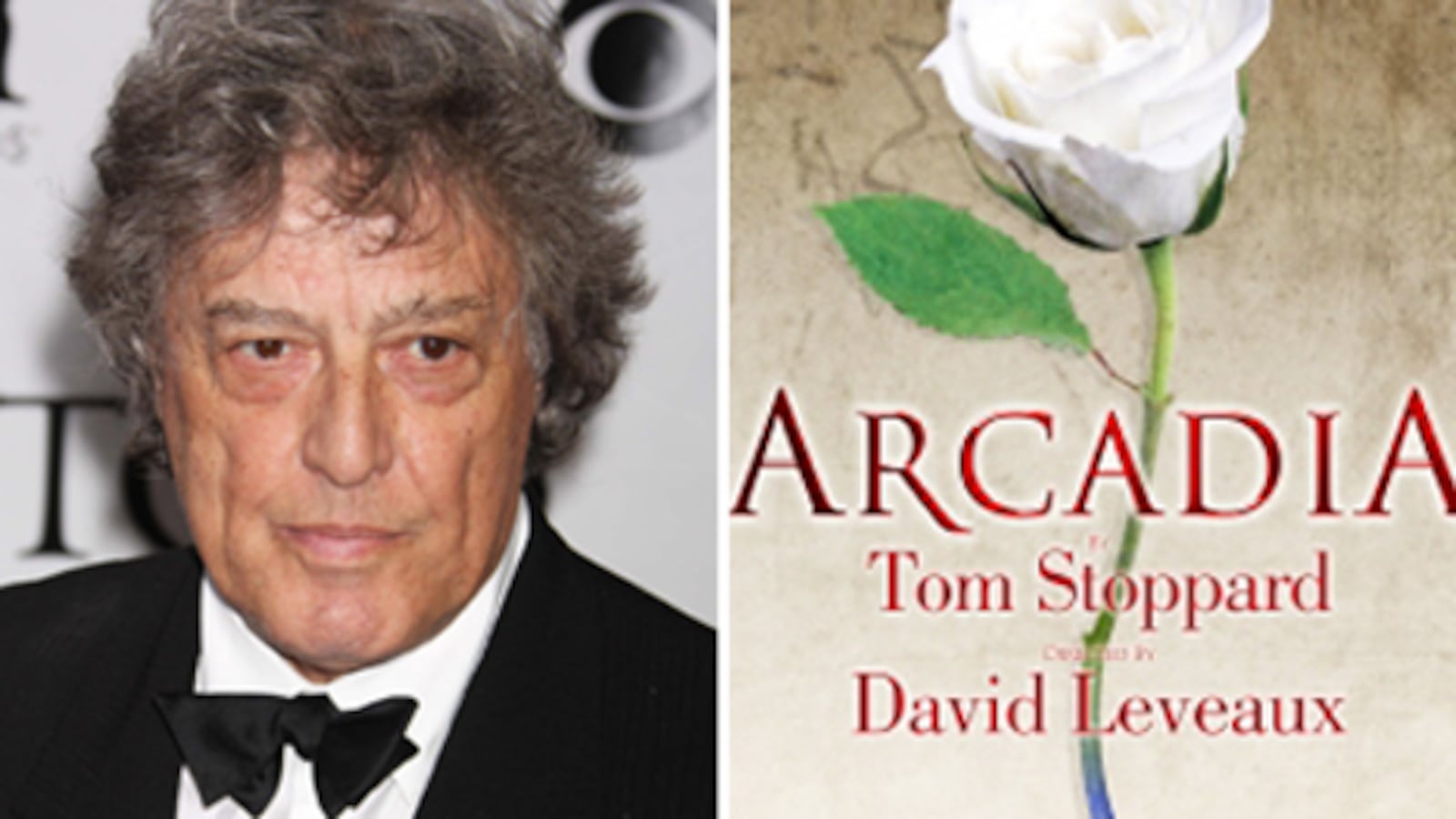

Tom Stoppard may be the Shakespeare of the modern age. His plays, from Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead to Coast of Utopia, are brilliantly crammed with ideas, philosophies, and history. When his most commercially popular play Arcadia first opened in 1993, critics gushed that it was an enduring masterpiece, and the West End revival two years ago moved some reviewers to call it "the greatest play of our age."

Now director David Leveaux has brought the show to Broadway with a luminous cast that does justice to Stoppard's enthralling dialogue. The near-perfect blend of humor, tragedy, and love in this play, which opens tonight at the Ethel Barrymore Theater, should shake any audience to the core. But at intermission during a recent preview performance, the man next to me grumbled that he had no idea what was going on.

"Really? I can't imagine that," says Stoppard, when told of the exchange. "I suppose some in the audience might miss a few things, but it's really just a detective story."

A detective story set in two different centuries with references along the way to Newtonian physics, iterative algorithms, and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Or as one of the characters in Arcadia says, "It's wanting to know that matters."

"A lot of it has to do with entertaining an audience," says Stoppard. "This is a storytelling art form, and if the primary motive is to educate and convert, you should be writing editorials, not plays."

At 73, Stoppard is intense and charming—and now he pauses to reconsider what he's just said. "I'm listening to myself and thinking it's nonsense. Many playwrights pick up the pen with something they want to say."

Stoppard's ability to see many sides of a question—in real life and on the stage—gives extraordinary depth to Arcadia. Profoundly moving, the play is both funny and fervent, filled with references to love, sex, and the death of the universe.

In 1809 at the English country house Sidley Park, a suave tutor (the dashing Tom Riley) introduces his pretty young charge Thomasina (Bel Powley) to everything from Fermat's Last Theorem to the definition of carnal embrace. A swirl of activity ensues, with a cuckolded friend, the challenge to a duel, and the lady of the house designing a garden. The characters drift off stage, but the next scene continues in Sidley Park—now in the current time. One of the tutor's books has been found by a modern-day Lord Byron scholar named Bernard Nightingale (Billy Crudup), who visits with a theory of what might have happened generations earlier.

In alternating scenes, the audience watches both the scholar's theory—and the 19th-century reality—unfolding.

“I would recoil from calling it the message of the play, but the conclusion is that we don’t and won’t ever get history right,” Stoppard says.

"I would recoil from calling it the message of the play, but the conclusion is that we don't and won't ever get history right," says Stoppard. "Here it's very simple: Who wrote the notes and why? Was there a duel or wasn't there? But it's very Rashomon—you interpret the past by your current point of view."

During preview performances for the Broadway production, Stoppard sat in the audience taking notes. Like Hamlet, the play is performed often all over the world, and each cast brings its own perspective.

"It still surprises me how many Bernards there can be," Stoppard says. "I bought into the character interpretations, so I focused on the rhythms of dialogue. You have to shape a sentence so that it dives across the net. It's like hitting a ball in tennis—the wrong shape and you'll put it into the net or past the baseline."

A play praised for its perfection doesn't require rewrites, but Stoppard did make one small change, altering a line where Bernard jokes that with certain mathematical proofs, D.H. Lawrence could be shown to have written Pinocchio.

"When I was a kid, I was mad for a series of books called Just William about a rebellious, middle-class schoolboy," Stoppard says. "Until a couple of days ago, Pinocchio was Just William. But I realized not many people in America know that series, and I thought I have to do something. Theater is a pragmatic art form."

A thoughtful purveyor of intellectual ideas, Stoppard also cares about a mass audience. Knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1997, Sir Tom won an Academy Award the following year for his screenplay for Shakespeare in Love. Hollywood rumor says he has polished scripts, uncredited, for some movie blockbusters, and he's also busy with TV projects. "The whole world of culture is so connected now with the world of consumerism," he says. "I'd generally rather be alone at my desk, but as a playwright, you're part of a collaborative business."

By the last scene of Arcadia, characters from the two time periods occupy the stage together, echoing each other's lines across the centuries and even turning the pages of a book at the same time. They never interact, but the past feeds the present. Young Thomasina turns out to have been a natural genius who died before she could finish her equations. Her mathematical insights are taken by Valentine (Raul Esparza) for his own work. The anguish of having limited time pervades the play—but provides no dark cloud for Stoppard himself.

"It's an intellectual abstraction that we are running out of time and living in a doomed universe," says Stoppard. "Entropy is winding down, but we don't know what's winding up. You'd be crazy to worry about it."

After discussions of chaos theory, predeterminism, and Cabbalistic proof that the world is coming to an end, the play ends as it began—with Thomasina contemplating carnal embrace. She is less interested in math than in learning to waltz. Before a blaze of emotion, the tutor takes her in his arms and dances her around the stage.

"We have no time left," one character says.

"That's what time means," another replies.

Stoppard may be his generation's most gifted and cerebral playwright. But if he doesn't make you cry, you haven't been paying attention.

Janice Kaplan is a television producer and former editor in chief of Parade magazine. She is the author and co-author of 10 novels, including the bestselling Mine Are Spectacular and The Botox Diaries; her most recent is the mystery A Job To Kill For.