Tony Earley’s cleanly crafted fiction, most notably in his two well-regarded novels Jim the Boy and The Blue Star, has long been marked by vivid realism, a compressed earnestness and a visceral sense of life in a bygone era. Yet in retrospect, it’s not hard to see how those works—a matched pair following the trajectory of Jim Glass, a reliably decent resident of tiny Aliceville, North Carolina—laid the groundwork for his latest effort. Studded with his penchant for finding enchantment in everyday lives, their folk tale patina presages the more overt magic running through his new collection of short stories, Mr. Tall, which includes the ghost of Jesse James, a cryptozoologist, and a 70+ page novella teaming Jack the Giant Killer with Tom Dooley—star of an Appalachian murder ballad—against a rabid talking dog. Throughout, these new fables remain tethered to Earley’s trademark preoccupations—the strange alchemy by which people connect, a heartfelt grasping for what comes next.

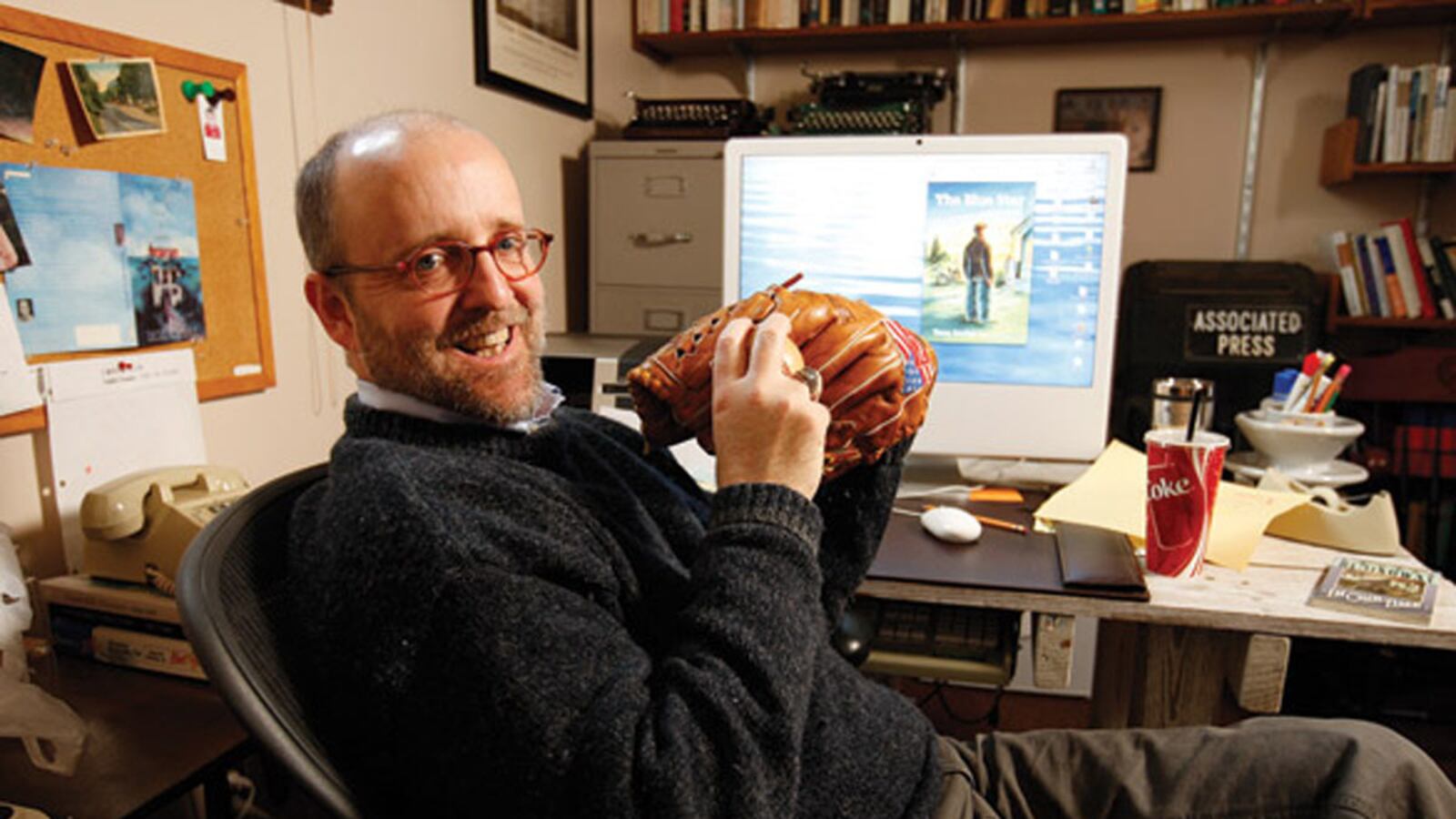

In the edited conversation below, Earley, 53, talks of Ernest Hemingway, technical challenges, and stumbling toward the light.

As a writer, you’re known for your realism. Where do you feel the weirdness of your latest collection came from?

That I have no idea. In my first collection of stories, it was pointed out to me then that I had lots of really tall men and really tiny women, which was a shock to me because I really hadn’t thought of that or where it came from. And so where the weirdness came from I couldn’t tell you, but I have had for a while a fascination with ghosts, and the idea that there’s something else going on that we can’t quite access. I guess that current fascination informs the stories.

And I think part of it was in response to being such an extreme realist writer. I wrote two books that were so straightforward. The prose was so compact and controlled that I just really wanted to do something else. And in some ways [the novella at the end of the collection] “Jack and the Mad Dog” just sort of set me free. I had such a great time writing that. Honestly, I can’t remember the last time writing was that much fun.

Did that story change how you conceived of the whole collection?

Well, at first it sort of frightened me about the whole collection. Because some of these other stories have a weirdness in them, but it’s a weirdness sort of within the realm of realism. But then I happened to think by calling the book Mr. Tall, which in addition to the name of the story it could also be a tall tale, I realized this does kind of fit. It’s just the weirdest of the weird.

It’s been about six years between this collection and your last novel. How did these stories start to emerge?

They came out very slowly over a long period of time. The oldest piece of fiction in there, “Bridge,” was from 1995. Often I’m accidentally writing something while I’m writing something else—that’s always been the way it worked.

There are a couple of, for lack of a better word, failed novels in there. Originally I envisioned “Mr. Tall” as a novel, and originally I envisioned “Jack and the Mad Dog” as a novel. But sometimes pieces get so far, and that’s all there is. Originally for “Mr. Tall,” I wanted to start where [its Depression-era teen bride] Plutina got married, go up to where she’s an old woman in “The Cryptozoologist,” and go beyond that to her death. But there were the two stories and really sort of nothing in between.

At what point in time did you see how they were all going to be interrelated?

“The Cryptozoologist” and “Have You Seen the Stolen Girl?” were back to back. I thought, well, I’ve got Jesse James, and I’ve got Big Foot—those two kind of talked to each other. And then I started thinking more consciously about the way other stories might fit. “Mr. Tall” is sort of “Jack and the Beanstalk,” and that started to talk to “Jack and the Mad Dog.” I really liked the way that it came together. I didn’t sit down in 1995 and plan for it to be that way.

A couple of your characters here are painters—one failed. You’re also a painter—

Not really. There are some bad paintings hanging in my house that I might have done. I’m certainly not going to call myself a painter. I constantly have ideas for paintings and sculptures that I do not have the facility to do. I’ll sort of see this thing in my head and think, wow, if I could do that, it would really be good.

But … I’ve never learned to be reticent, but after a period of depression, when my creativity comes back, it tends to be visual. So I will make something rather than write something.

The painters and sculptors who pop up in the collection—does their work come from putting these ideas into your writing instead?

This is the first time I’m thinking about what you just pointed out. I do think my fascination with visual art did work its way into my stories in that way. Rose [the main character in “The Cryptozoologist”] and I have kind of the same job, which is depicting this valley. And [the folk artist featured in “Yard Art”] William Edmonson is actually a real person, and there is a wonderful museum here that features his work. The pieces are amazing. I used to have this fantasy that—this is partly where Jesse James [in “Have You Seen the Stolen Girl”] came from—somehow there was a forgotten William Edmonson sculpture in the crawl space under my house. Of course there wasn’t. But I might have crawled under there to look. I’m just saying.

I’m curious about the impulse in your fiction, to which you just alluded, to stick with your characters over decades and revisit them in multiple stories.

That’s another one of those things I can’t really explain. It’s maybe more place than character. I have an imaginary place, and these are the people who live there. That valley that Plutina and Rose live in, I have a very visual memory of it—when I close my eyes I can see it.

I have no plans to return to Aliceville, but I wouldn’t be surprised if those people eventually showed back up at the door with their suitcases, and I’ll let them in, even if I might regret letting them in. But I just am really in love with, and always have been in love with, the short story form, and that’s what I want to do right now.

What about that form entices you so?

I actually think that it’s the set of muscles I have, more than novel-writing muscles. I get out to about 250 pages on a novel, and I think it’s time to wrap this thing up, and maybe to some degree I write novels for the wrong reasons. In this business novels are the way people keep score. I think I wrote two good novels, but it certainly wasn’t a natural act for me the way writing short stories is. If all things were equal I would never have written a novel. I would have been perfectly content writing short stories. I think the only people who buy short story collections are MFA students. That’s fine. I can get my stories out into the world, and they‘re not going to make me wealthy, but they are part of the conversation. That’s all I wanted to do, be part of the conversation. And since I have written two novels, that let me get into the party. Now that I’m inside the party I can mingle.

How did your favorite short story writers shape your sensibility?

When I first started out, the biggest influence I had was Hemingway. I think he invented the American short story template that we’re still using and dealing with. As far as the technical stuff, of using the lines to write in between the lines, saying more than one thing in the same space, I studied him really closely trying to figure out how to do that stuff. When I went to graduate school, I carried his books around like the Bible. And I’m a great admirer of Eudora Welty, and Flannery O’Connor’s short stories. Those were the big three. I’m a huge Lorrie Moore fan. And now she’s my colleague [at Vanderbilt University], which I’m largely responsible for, so I’m very pleased with myself about that.

What did you take from Welty, O’Connor, and Moore?

Lorrie would be too hard to steal from, because she sounds only like Lorrie Moore. But what I really admire about her is, I think she’s the greatest user of figurative language that I’ve ever come across. Whenever I see the word “like” in a Lorrie Moore story, I know something extraordinary is about to be on the other side of that. As for Welty, the story that influenced me most of hers is “Why I Live at the P.O.,” which is the exemplar of how to write a first-person unreliable narrator. The story is absolutely brilliant. And Flannery O’Connor stories are just so vivid. The people are vivid, the way they talk is vivid, and the landscape they live in is vivid. She writes about a world that is brighter than the world I live in. I love going into that world, which is just a little off center.

Years ago, you talked about how you thought of Jim the Boy as a kid’s book for adults. Kids books are all the rage for adults now. In your mind, what separates a kid’s book for adults from a kid’s book that adults are reading?

I set out to write an adult book, but using some conventions from classic young adult books. It was just another way of doing Hemingway, and saying more than one thing in the same space. A 12-year-old can read Jim the Boy and then read it 10 years later and have an entirely different experience. When I was assembling the tool box I wanted to use when writing Jim the Boy, I loved that idea of writing a book that appeared to be simple but wasn’t. I loved the technical challenge of that. I always love a technical challenge.

Did you set any technical challenges with this short story collection?

Certainly I did with “Jack,” in that it was such a radical departure. There was a lot of prose in there that’s not my usual style of prose, much longer rolling sentences. I loved writing those sentences because I hadn’t written any sentences like that in 20 years. But that’s probably the only really technically daring one in the book.

Your fiction is preoccupied with the past—even the contemporary stories have an aura of looking backward. In one of your essays, “The Quare Gene,” you write explicitly of “losing the small comfort of shared history,” and how “[m]y characters, at least, can still say the words that bind them to the past without sounding queer, strange, eccentric, odd, unusual, unconventional, or suspicious.” What captures you so about the past?

I think that no matter how hard we try that we fail at life a lot of times. And looking back is a way of imagining that that had turned out differently. Of course, that’s not the way the stories often go, because I look back and things turn out badly. But … you know, my children are my greatest joy, and they’re growing up to be wonderful kids. But still I look back and wish they were younger, and I could do it all over again. I’m just not a forward-looking guy. And I just think that my parents’ lives when they were kids on a farm and my grandparents’ lives were so much more interesting than my own. People in those generations, in the country, they knew how to do things. They could fix things and grow things and work with animals and do medical things and butcher pigs and put up preserves. I don’t know how to do anything pretty much, except sports.

I don’t want to give up my smartphone, and I don’t want to idealize the past, because I don’t think that when the past was the present, people’s lives were any better than they are now. But as a writer, it’s just sort of a practical fascination that I have. It’s a whole different level of subject material and what my whole life brings to bear.

Almost every one of your characters in the collection is paired off, often in long marriages. What adds a richness to the stories is the way you take relationships themselves as an overriding theme.

There again that falls back into that looking back at the past—if I’d only done this differently, if I could only go back and not do the hurtful thing that I did. Thinking about, with all that is in the past and the way it shapes the present, how do you go forward into the future? That’s what I’m writing about with all those couples. We have this history, where do we go from here? I’ve been married for almost 21 years, and that marriage is the dominant interest in my life. That and being a father.

In American fiction, we tend to write about things that go bad. Lots of things blow up. I just don’t think our lives are as bad as our art would lead us to believe. I like writing about people who aren’t threatened by serial killers and children who aren’t molested. I like to write about people doing the best that they can. I want to celebrate the people who continue to stumble toward the light, even if they’re doing it poorly. I tell my students, make a character have to decide something. That’s where stories live.