“This year I felt I was getting rings run around me.”

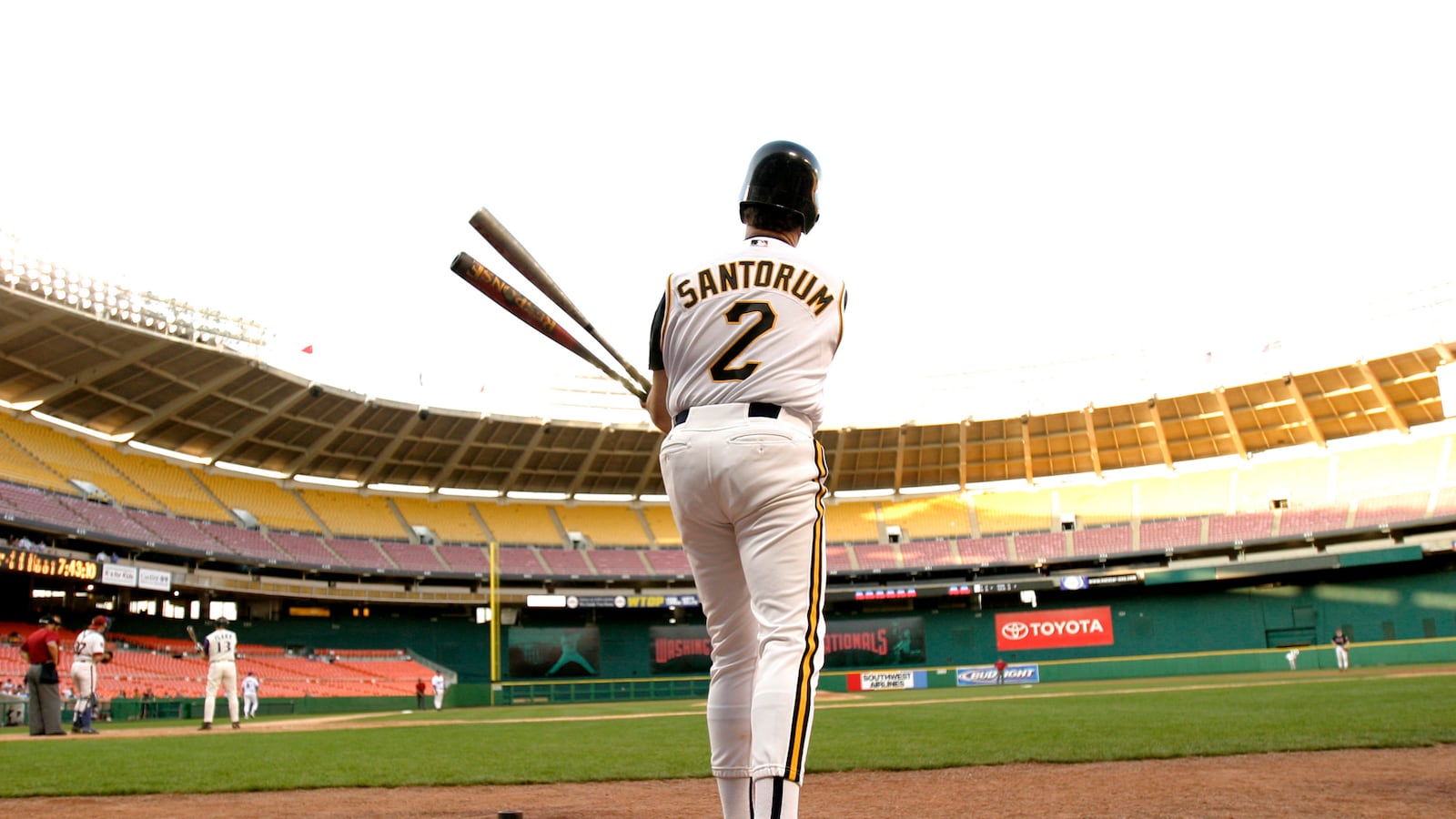

Rick Santorum is having a bad week, not only because he suspended his presidential campaign on Tuesday, but because he hadn’t time to prepare for his fantasy baseball draft this week. The former Pennsylvania senator’s team, For The Glory, named after the first three words of Penn State’s fight song, was about to start its 17th year in his long-running league, and for some reason he hadn’t had time to get ready for the big day.

Santorum, who finished second in his league last year, is trying to make it back to the top.

In his first interview since dropping his presidential bid, Santorum wanted to talk about the things that really matter, so no Etch a Sketches, aspirins, or wars on caterpillars—but baseball, and a bit of football and hockey, too.

The seven-time league champion, who stayed dedicated to his team through the distraction of his U.S. Senate career (and won five years in a row while serving in that chamber), credited his success to “doing a lot of off-season reading.” To win, he said, “you’ve gotta do your homework.”

Because he’s a dedicated Pittsburgh Pirates fan, Santorum plays in an American League-only league with 12 teams of 23 players apiece, the type of league that’s “so thin, you end up drafting middle relievers and backup infielders.” He chose this type of league not because he’s a baseball nerd—though he is one—but to avoid putting himself in an awkward position where he wanted the Pirates to win but players he owned on the other team to do well, let alone “feeling guilty that [he] didn’t draft a hometown team.”

Despite growing up in Western Pennsylvania, Santorum confessed to a scandal that his opponents’ opposition research teams failed to dredge up: he grew up a San Francisco Giants fan in the mid to late 1960s. His two favorite players, he says, were Willie Mays and Juan Marichal. It was Mays who first got him started watching the Giants. After that, he became infatuated with Marichal, the fireballing Dominican righty with the high leg kick, who remains “the coolest player I’ve seen in baseball.”

It gets worse: Santorum didn’t grow up rooting for any Pittsburgh teams. The Steelers, still in their pre-Chuck Noll nadir, “were horrible,” he says. “Nobody watched the Steelers.” Instead, he rooted a bit for the Dallas Cowboys because he “loved Roger Staubach.” However, he was “quickly disabused of that” and now “bleeds black and gold.” In hockey, prior to the Penguins coming to town in the NHL’s 1967 expansion, Santorum rooted for the Chicago Blackhawks because of Tony Esposito, to whom he was drawn to as “an Italian kid in an Italian neighborhood,” and because of Santorum’s childhood desire to play goalie.

Santorum didn’t become a true sports Yinzer until he went to college at Penn State and found himself in an environment where about half of the people subscribed to an ideology and point of view that he found noxious. They were Philly sports fans.

Although Santorum “never hated the Phillies,” since “they weren’t any good most of the time” and is indifferent about the Eagles, he loathes the Flyers. He says he’s been “very public about hating the Flyers” and that while he would wear an Eagles hat or even Phillies gear while campaigning in Eastern Pennsylvania, “you wouldn’t catch me dead in a Flyers hat.”

But, for all his talk about other sports, Santorum’s true love is baseball.

Baseball “is a mental game,” he says, “a game of stats and strategy, when to throw, when to steal.” He has a very simple opinion of the designated hitter as such: “I hate the DH.”

But to follow his fantasy league players, he ends up watching mostly American League games, where “you don’t see guys bunt and you don’t see guys move runners over, you don’t see the game played the way in my mind that it makes sense for it to work.” Because he stays up late working, he says, he “usually ends up watching a lot of West Coast games” on his MLB package, with “all the AL games on the split screen along with the Pirates” if they’re on.

Santorum says he’s a little optimistic about his Pirates this year, saying “they have a good enough nucleus to potentially break .500, I don’t hold much beyond that.” He goes on to lament that the team has been “disappointing in some respects [and that their] owner is not deep-pocketed.” Santorum adds that “I think he [owner Robert Nutting] is a good guy… but just doesn’t possess the resources necessary to win.” Instead, his World Series pick is the Detroit Tigers, who have, in his opinion, the sport’s best manager in former Pirates skipper Jim Leyland, and just need their pitchers to stay healthy.

While Mitt Romney may be friends with NASCAR team owners, Santorum’s league is a more down-home affair, with his brother Dan also playing, as well as “two guys who worked for me at one time,” and who he says now “try to conspire [on] how to beat me.” The competition is “cutthroat.” While one of those former staffers now serves as the league’s commissioner, he’s scrupulously honest,” Santorum says, “even though he wants to do everything he can to beat me.”

Santorum’s strenuous retail campaign in the primary, including months where he effectively lived in Iowa, made it “a tough year to keep it going” with the league, he says. You only get “a few minutes every night [and you’re] not doing as a good job.” He lamented that, because of the campaign, he was always the last to know when a player was called up from minors.

To Santorum, the secret to success in fantasy baseball, or anything else, is “just knowledge.” But his campaign kept him from scouting prospects as thoroughly as he has most off-seasons. During his draft Wednesday, he “felt I was getting rings run around me” as other teams were “drafting names I hadn’t heard of.” Things got worse Thursday, when he discovered that one of his players, Lorenzo Cain, a relatively obscure center fielder for the Kansas City Royals, had just been put on the disabled list, leaving him scrambling to scout a replacement.

Santorum’s drafting philosophy has been to avoid gambling on rookie “diamonds in the rough” and instead take the sort of solid players “who’d hit .275 with 20 HR and 75 RBIs” rather than go swinging for the fences. “There’s so much hype with these young players and so few of them do anything,” he said.

That steady-grind philosophy fell just short for him in a different race this year, but he’s hoping it will leave him on top at the end of his new contest.