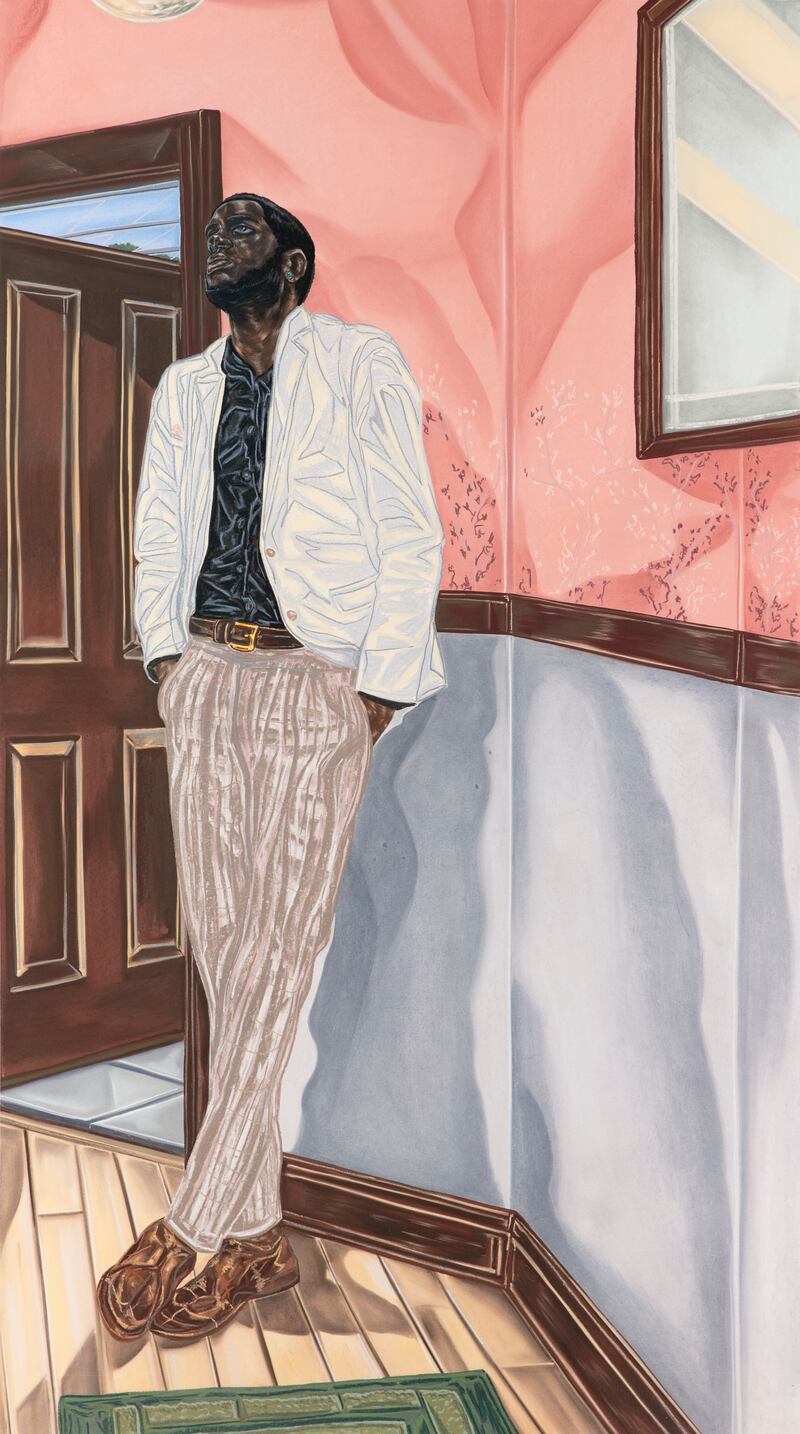

Art doesn’t have to be over the top or convoluted to be radical. The best pieces, like that from Toyin Ojih Odutola’s To Wander Determined exhibit, have inherent messages embedded below the surface. Her portraits, drawn in charcoal, pastels, and pencil, are of two Nigerian families donning stylish contemporary clothes in opulent spaces.

The drawings seem more like photographs or snapshots into the day to day life of wealthy families. What makes these images so profound is how they depict wealth in relation to blackness as ordinary. Her work is not ostentatious or overtly political. In that, she’s able to use blackness as a tool to normalize wealth without perpetuating concepts of exoticism or otherness often associated with black art. In her work, black skin is not tied to racial stereotypes, nor used for entertainment. The uninhibited nature of the images translate as real, even if in reality, wealth is seen as a paradox to blackness.

Recently, while discussing immigration reform, President Donald Trump referred to predominantly black countries as “shitholes” and called for more immigrants from predominantly white countries like Norway. Trump draws a blatant racial comparison that suggests blackness as inferior because he associate it with poverty and whiteness as superior because he associates it with wealth. It can’t be denied that wealth is power in America and rendering black skin to poverty is blatantly classifying it as powerless.

Throughout American history, this imposed perception of powerlessness towards African Americans has allowed for cruel injustices without any repercussions. In 2015, in response to the countless instances of police brutality against African Americans, Ojih Odutola conceptualized a series, The Treatment, to challenge whiteness as concept. The fact that black people are killed on baseless associations with skin color filled her with indignation. She drew the outlines of famous white men and filled in their skin with black ink from a ballpoint pen (her signature style). Her goal was to show that skin color is merely a construct. Images of blackness in the U.S. have long been riddled with lies and Ojih Odutola’s work rejects it as objective truth.

Ojih Odutola is herself an immigrant from one of the countries Trump downgrades, Nigeria. Her father is an exemplary chemist who worked for the U.S. government and her mother is a nurse. Her family’s success story is not unique. Most immigrants come to the U.S. in search of opportunities. Yet, immigration remains a point of contention considering the looming DACA deal and a partially implemented travel ban. It’s clear that anyone deemed as other is problematic, especially those with darker complexions. Ojih Odutola’s portrayal of black skin is incredibly important in a political climate that rejects otherness and rejects blackness as powerful.

In our conversation, she addresses Trump’s views on immigration, the black lives matter movement, blackness as a “dangerous” construct, and more.

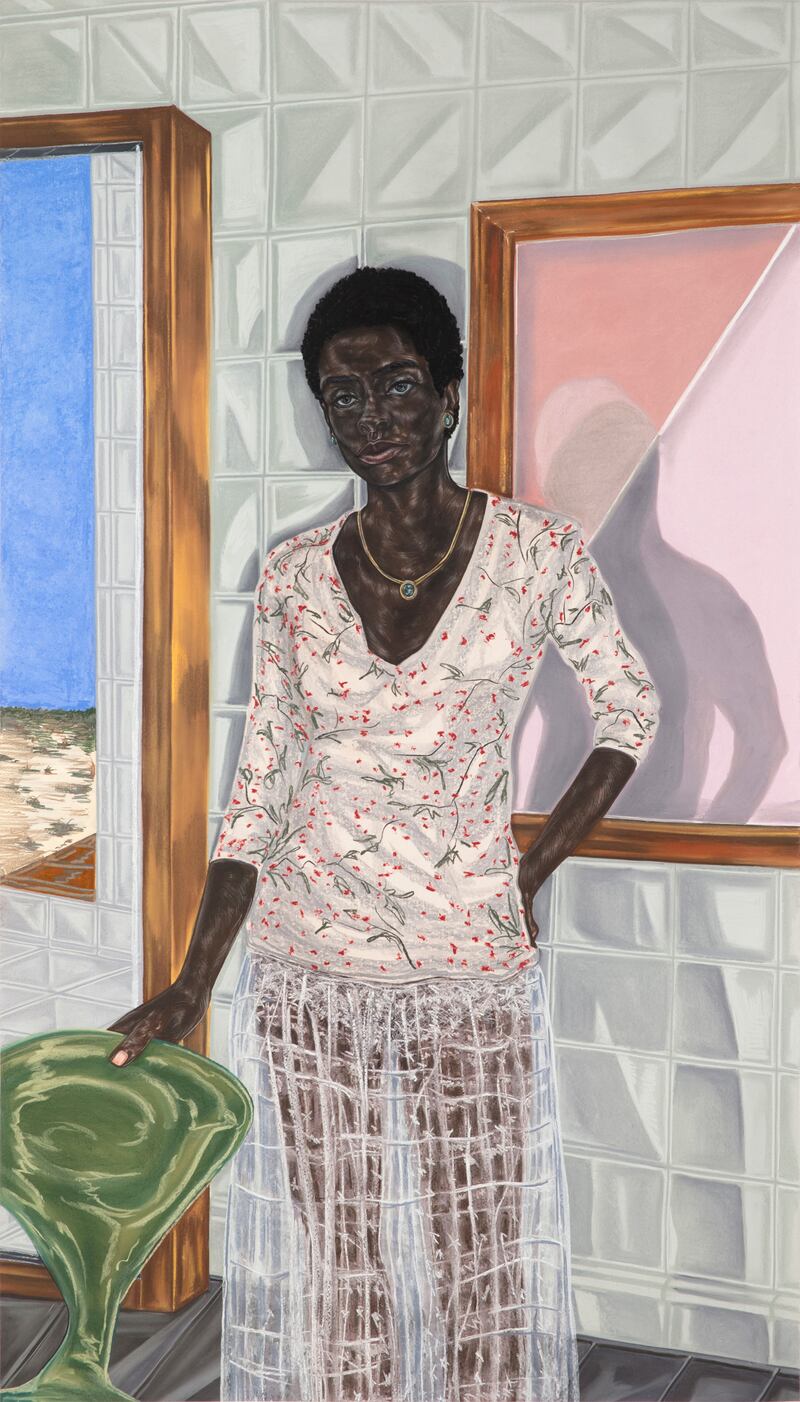

Pregnant; 2017. Charcoal; pastel and pencil on paper; 74 1/2 × 42 in.

Toyin Ojih Odutola /Jack Shainman GalleryWhat was it like moving to Alabama as a Nigerian immigrant? Did it inform your art? If so, how?

When we just came to America, we moved to California. I was five and felt pretty excited to come America. I’d just watched the Wiz. I thought America was this magical kingdom. It became a reality very quickly that it’s not what it’s cracked up to be. For me, moving to Alabama was like a culture shock. Growing up in California, Berkley, it was a very multicultural setting, so I didn’t really feel like my being a migrant was that different.

But coming to Alabama and being black with all of that storied history and having to mitigate through that in a space that was not my home was incredibly difficult. I think the thing that really hammered through all of me was this idea that I was now not only an immigrant but black. I don’t even understand what that means because I’m nine. I had to sort of crash course into it. There was a lot of hard times and moments where I really hated being there. Then something magical happened in that, I discovered drawing. It was a bit of a coping mechanism, but sort of an investigative tool. I was able to build a world for myself that was outside of my being seen as a one-dimensional person.

Looking at your art, the figures appear uninhibited or untethered to the negative associations with blackness? Was that your goal?

People would ask, “why are your figures so underwhelming or mundane or regular?” They are not ostentatious or bombastic. I did that trying to make regular blackness. I think the problem with blackness is that it’s viewed as this exotic thing and quite frankly, that exoticism is exhausting. People look at blackness and expect to be entertained because they see it as exotic, but it’s real.We still have to get up in the morning in this blackness that is imposed on us. And if I am still seen as this other that is different from what is normal vis-à-vis whiteness.

That’s not my interest. My day-to-day interests are trying to pay my bills, getting milk, et cetera... Regardless of you being black, that is stuff everyone deals with. The difference of course is that the blackness is socially imposed in a way that is murdering people. There’s always these responses that you get from well-meaning progressive white people who apologize for being white. It’s just like, you are still making it about you.

The thing that is so refreshing is not to be reminded about blackness by people of whiteness and apologizing for it. I do that with my pictures; I’m not having my figures apologize for their blackness. They are what they are and that is a fact. I want to make that as unremarkable and as bland as I can. That is an effort to get there because I am dealing with a surface and a material that is still viewed as exotic and contentious. But at the same time, I understand that there is no one dimensionality to this here. It’s an image and a story and you can take from it whatever you want, but this blackness that I’m rendering is not for entertainment at all. I’m not an entertainer. I’m an investigator.

Years Later – Her Scarf; 2017. Charcoal; pastel and pencil on paper; 72 × 42 in.

Toyin Ojih Odutola/Jack Shainman GalleryHow did you grapple with this idea of blackness in your art?

I think of blackness as a material in the same way that I think of whiteness. It gets very problematic when people look at blackness as something that actually exists in the world. Blackness is something that is imposed on people. It’s an imposition more than an identity.

When I think about skin, it’s my engagement with a tool that is used to demarcate and create these parameters and barriers between people. It’s a power dynamic at play. It’s not about you and me waking up in the morning and just living our lives. It’s a societal implementation only allows us to exist in certain spaces. One of the things that I’m always trying to push for with the style that I employ is that blackness impounds on our bodies, housed in our culture, housed in our representations, our images, even status. It isn’t still, it’s material, it shifts.

And if you are going to impose this lie onto my very body, on my very skin, I’m going to show you how many layers of it lies there. And I am also going to reveal to you that the blackness you impose is mine to do whatever I want with. I still walk in this skin and this skin is read as blackness. I think that’s what makes it so fascinating to me as an art material and concept to delve into, because then you realize that it’s a lie or an illusion.

Why do you think blackness is viewed as problematic in art?

In one of my early interviews, someone was asking me about my style and was like, “why does it look like reverberation”? The interviewer was describing my style as sort of this scratching or scarification. She said it was very tense. To her, the layers of marks was very dark and seemed almost impenetrable. It’s a fascinating thing that people read blackness as this contentious impenetrable territory. When in fact it is at most a nebulous tool. It can be so many things.

If you want something that is the same in every single concept, that’s really boring. If blackness is somehow powerless or deemed as problematic, to me, those are qualities that make it so beautiful. I find it very interesting to engage with blackness and redefine it as something that can be anything in any place and at the same time in one place. It’s like trying to capture someone in a blurry photo, the photo is blurry, but does that make that photo any less real or beautiful? No!

What was the inspiration for your series? Were you, at all, inspired by the current political climate ?

When I started this entire series, I was attracted to Trump’s wealth pertaining to him, which was given to him. And he just built an empire out of that in real estate, which is the safest thing to invest your money in. So, It wasn’t exactly a genius move. Outside his bombastic language and shocking tactics he used it to entertain the American people into voting for him. I find it fascinating that his wealth is the thing that renders him qualified for presidency. It wasn’t his education. It wasn’t his experience. It was him being wealthy. And it was unquestioned.

Why is that? Because I find wealth to be just as demarcating as blackness. If you’re wealthy, you can only exist in a sort of world. You can’t really go to the projects. You technically could, but you really wouldn’t know what to do there. You can only exist in certain spaces as a wealthy person, because you are so indoctrinated into that world. That is a part of the lie of that label. Wealth doesn’t give you the skills to listen. It doesn’t indicate that you are patient or understanding. You expect certain things when your life is sort of handed to you.

So, there is a certain type of mentality involved with wealth that I found was very problematic being such a saving grace for the American people. They thought a successful businessman was going to come and save us. He only exists in one place and in one mindset. So how can he save you? You’re poor. He doesn’t understand you at all. He doesn’t know who you are. He doesn’t understand your plight. He doesn’t know you as a human being.

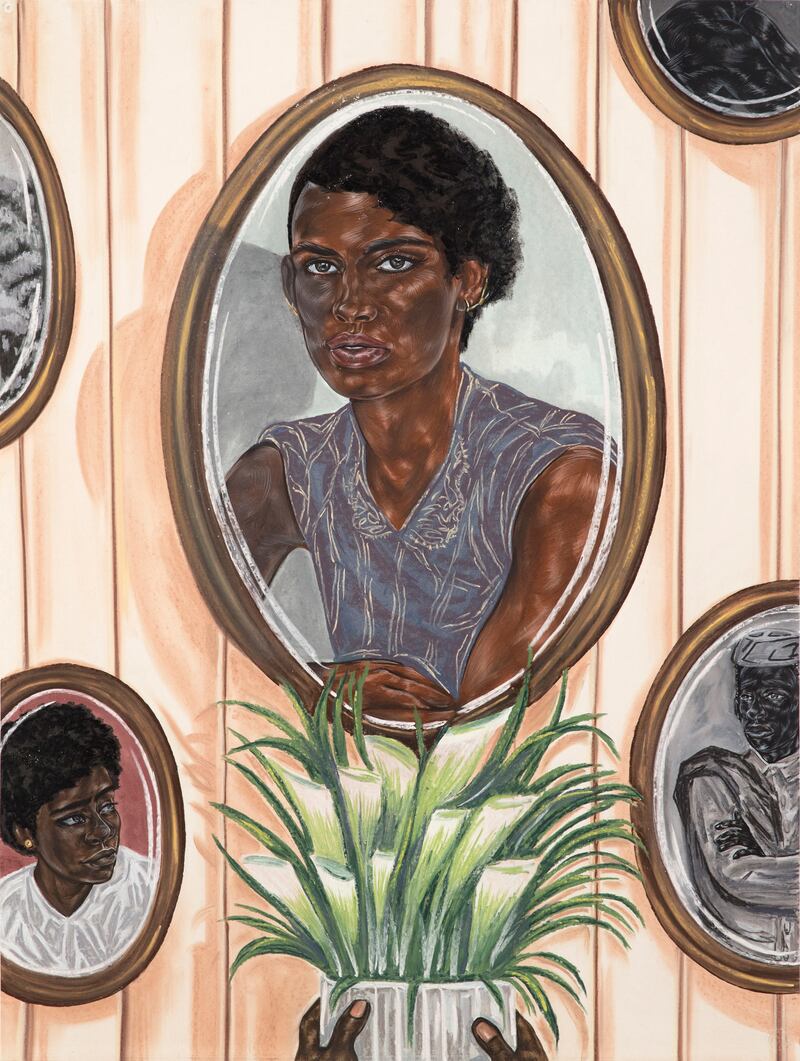

Wall of Ambassadors; 2017. Charcoal; pastel and pencil on paper; 40 × 30 in.

Toyin Ojih Odutola /Jack Shainman GallerySpeaking of Trump, he recently made a very derogatory comment about immigrants from predominantly black countries. What’s your opinion on his views, as an immigrant from one of the countries he targets?

I saw a video of a woman commenting after the whole shithole comment. She was basically praising Trump saying “I love this guy; he just says it like it is and I’m so glad he’s saying it.” It was a white woman, middle-aged, soccer mom kind of thing. She’s was like “what are you bringing to the table? You’re just leaving your shithole country and not bringing anything to help us Americans.” The thing that I really found a lot of people who are having these ideas and philosophies about saying immigrants need to go back literally have never left their home. It’s not even just about being an immigrant. It’s about travel. They don’t understand that experience at all.

Imagine if you just got evicted from your apartment, with no money. You got fired from your job. Your car broke down and you’re just knee deep in debt. So, you go to a friend’s house and beg them to sleep on their couch and they say “Sure, but what are you going to bring?” "You can’t just sleep on my couch if aren't cleaning my apartment every day.” I’m sure if this woman heard this, she would be like fuck you.

I’m still trying to wrap my head around what to do next to compete with life and somehow I have to give you something just for seeing my humanity. That what I’m always trying to get at with these conversations. The problem I’m having with the climate with immigration is that they really don’t understand themselves enough to comment on it. You may hate me to want me to go back to Africa, but I see you as a human being and I create work to help us feed our humanity.

Considering that Trump is perceivably well-traveled and has seen the world, why do you think he shares the same views on immigration as the woman in the video?

It goes back to the wealth thing. He travels only in specific circles. In any respect, I feel like his wealth is a crippling. If you’ve only been around rich people when you travel, that’s also indicative of who you are. Real travel is putting yourself out of a space that is comfortable. The travel he’s had is completely comfortable. He’s going from one mansion, one hotel, one Mar-a-lago to another. He’s not actually going to New Delhi and seeing people who live differently from him. The thing about the Norway comment that I find fascinating besides that very blatant Aryan race source is that his idea of a person is very small. Take this with a grain of salt, but I feel sorry for him.

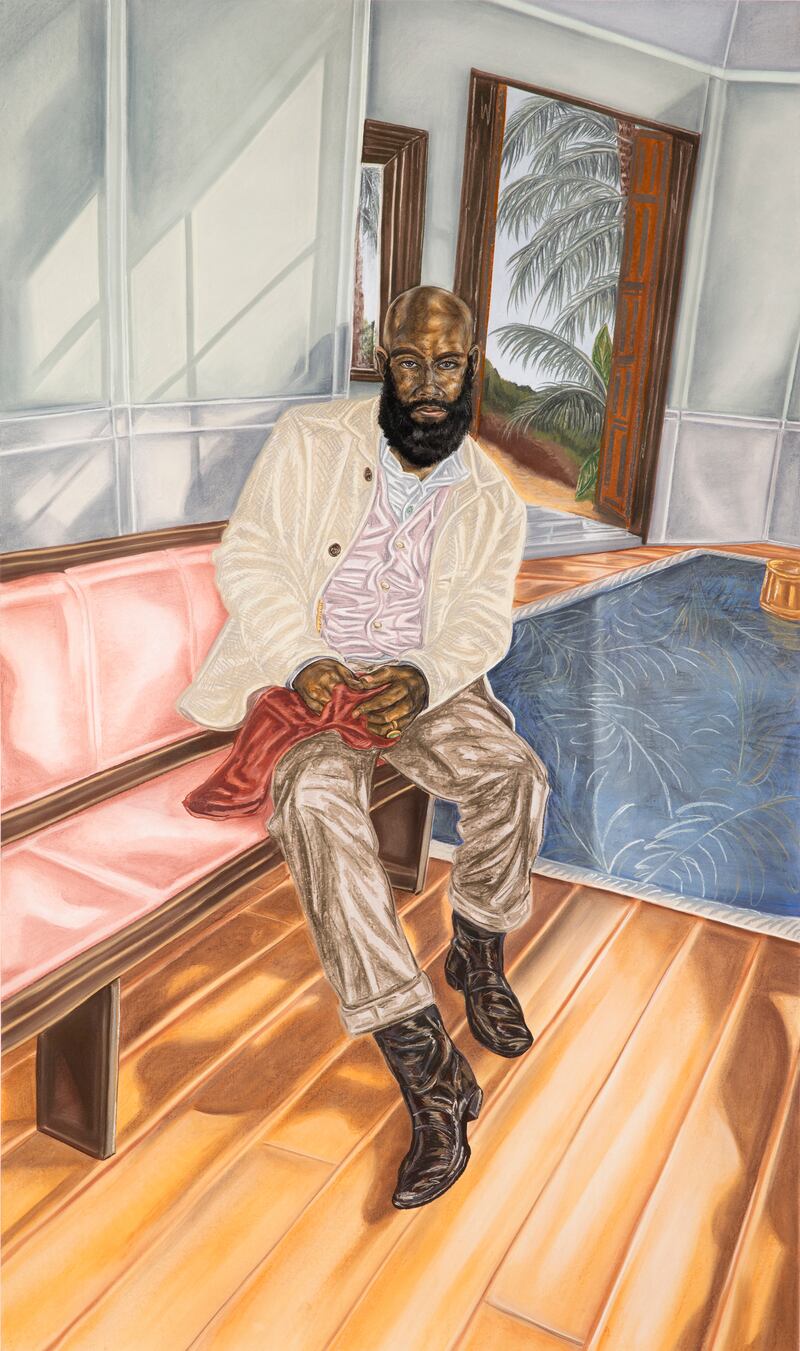

Representatives of State; 2016-17. Pastel; charcoal and pencil on paper; 75 1/2 × 50 in.

Toyin Ojih Odutola/Jack Shainman GalleryWhat would you say to immigrants who feel targeted by Trump or feel alienated in the U.S.?

People forget that a lot of our hospitals and research facilities are populated with very talented and brilliant immigrants, because we need them to advance whatever field they are being brought in for. We forget how many doctors there are from India, we forget how many researchers or physicists are from African countries.

For instance, my father was a chemist, who came here and worked for the government. I think people have this idea that the only people who come here are refugees or people who are going to suck the economy dry with welfare. We need immigrants because they help our society. That is not some lie or progressive propaganda. I think what this conversation is making glaringly apparent is how people don’t understand how diversity of minds works. It’s a crash course in the white house right now, which is a mess because everyone in there is exactly the same. No one is saying maybe we should consider a new angle. Everyone is on the same page which is not only authoritarian, but just completely dangerous.

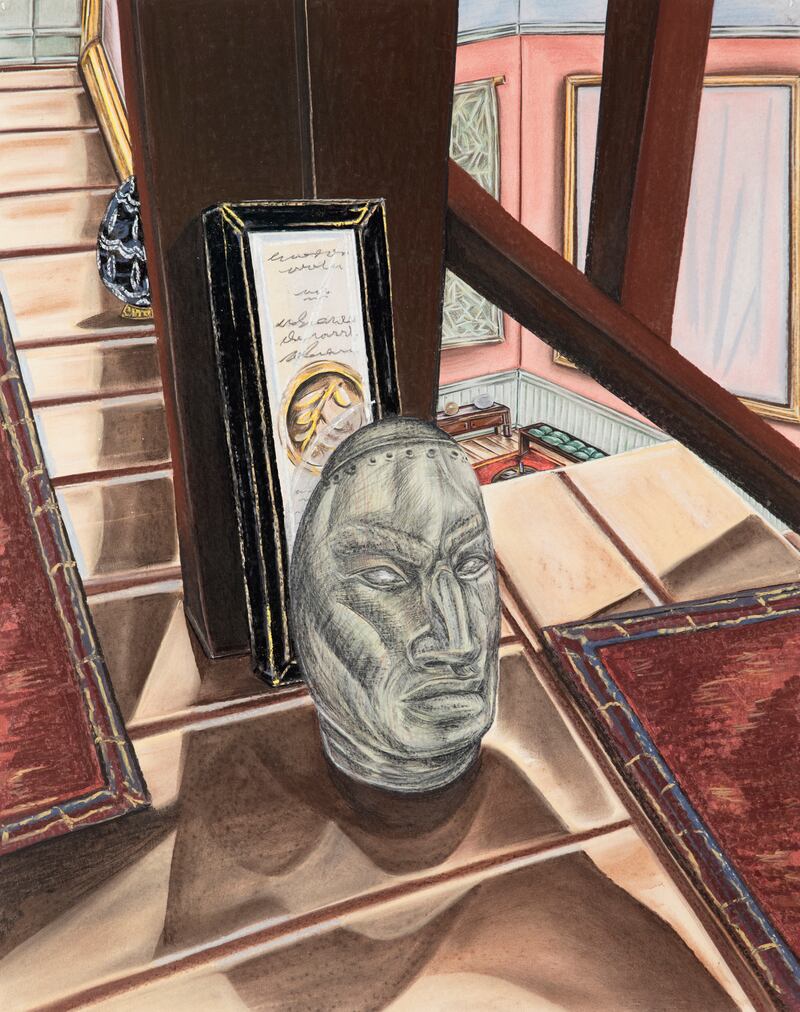

Excavations; 2017. Charcoal; pastel and pencil on paper; 24 × 19 in.

Toyin Ojih Odutola/Jack Shainman GalleryWhen it comes to conversations on Norway, it’s clear that they just want sameness and it’s going to be their downfall because that sameness is a crutch. The anger with the people who are coming in, I feel that. And I know exactly what that feels like to walk every day and feel like you don’t have the right to belong. It’s debilitating. No one leaves their country willfully. If you wanted us to move back to Africa so badly, maybe you should remove the colonialist sanctions there, because Africa isn’t our Africa. It’s a commonwealth with all these other nations.

With immigrants, people should commend them, give them love, and support just from a humanistic perspective or from the perspective of anyone who’s ever felt alone. It goes back to the woman in the video, the reason we’re having this conversation is because a lot of people don’t know what that feels like. I don’t know how to teach someone to be empathetic. That’s something you should have learned in the third grade. I understand it because I've had and continue to have that experience. If I could say anything to the immigrant community, I’d say try to rebuild your life and make it up as you go along because you’re an artist. That is a beautiful thing, but it’s not easy or romantic. Never be ashamed of the space you occupy because you’re making art.

Many people have described your art as political, what do you think about that label?

Political is a weird phrase. Whenever people say it, they always assume other. I think anyone who makes anything is political. Any mark you make in the sand is a political act regardless of your positioning. As a black woman, if I make a mark it’s immediately political. It was Kara Walker who said in an interview, you can paint a wall full of flowers and everyone will look at you and say why are you so angry? It’s real. That equation lies in the fact that whatever I do or say is going to be political because of the very nature of how I am viewed in society. I can paint that wall of flowers and people would as me “Is this about Trump”? And I’d say, No! It’s just a wall of flowers.

On the other side of that, I am not going to discount that I am being affected by what’s going on in our country. I think the thing that is bothering me is this growing global nationalism. It’s this nostalgic view of this ephemeral past that no one knows, but somehow everyone wants to go there. I’m not concerned about going to some nostalgic place that does not exist. It’s like fan-fiction, but I’m also not interested in this afro-futuristic alternative universe where everything is better.

At the end of the day, I have to be present with where I am now and what I am now. The most interesting thing for me is to see people separate from their image. I think people always see an image and say oh that’s a person and I’m like no its an image. It’s different, it’s a flattening. That process of analysis and investigation, I want to reveal that to the viewer and audience and make them understand that the image is the same as this nostalgic view and this futurist projection of utopia. Both are lies and if you get so invested in a lie, your life becomes a lie. James Baldwin said it best, people hang on to their hatred so much because at the end of the day if they remove that hatred, they are gonna have to deal with pain and a lot of people are in pain right now.

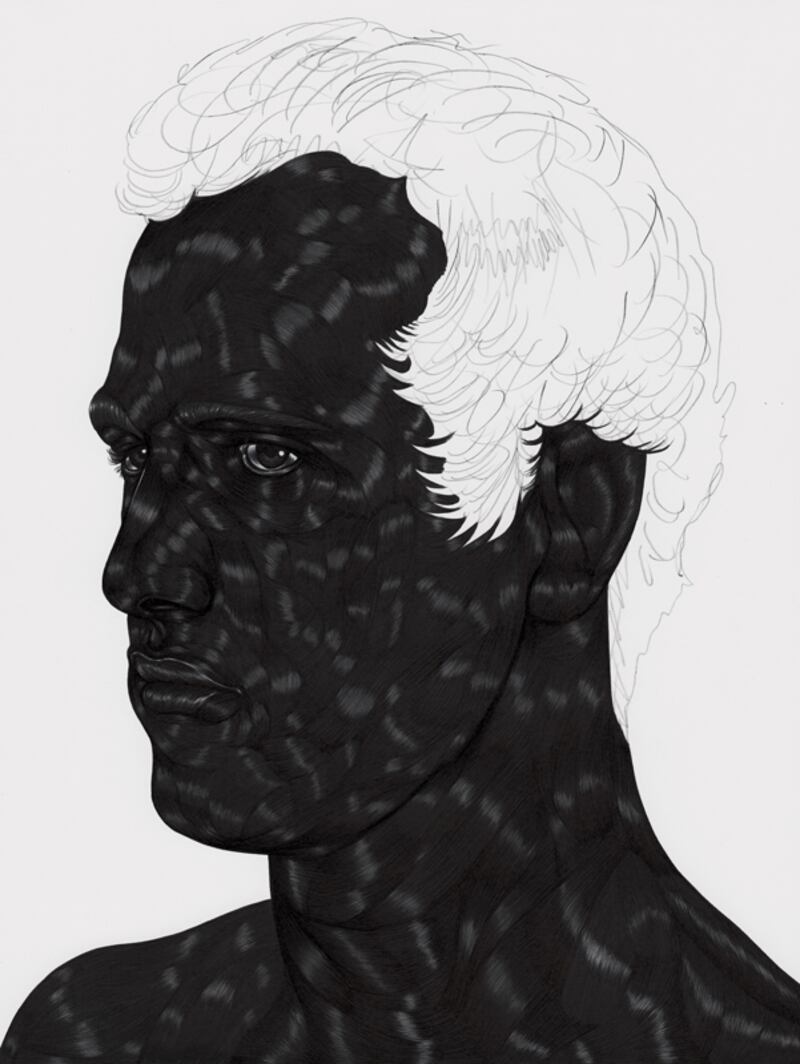

The Treatment 24; 2015; pen; gel ink; and pencil on paper; 12 x 9 inches (paper)

Toyin Ojih Odutola/Jack Shainman GalleryYour series, The Treatment seems like more of an overt attempt at challenging this hatred? What inspired you to create it?

It was in response to the backlash to the black lives movement. I commenced the series in 2015 and it was post Trayvon and Sandra Bland. It was a really tough time. People were dying, but we were not really prepared to see that in such a way we did from 2013 onward. There’s footage of our death every day. It’s interesting to me how the person who was murdered is somehow complacent in their murder. It makes no sense, because they are dead.

I didn’t want to depict black victimhood by putting up an image of Mike Brown, Sandra, or Trayvon. There were so many people killed. It’s a trauma and I didn’t want to traumatize people. I didn’t want to engage in that activity. I was very angry at the treatment of the victims. I was angry by how their image was manipulated by the press in a way that was so blatantly transparent and so utterly problematic and quite frankly insulting and dehumanizing. I wanted to turn the light off on their whiteness. That precious whiteness that could never be painted. It was the most glaring thing to see that blackness, even in death, is dangerous.

The Treatment 8A; 2015; pen ink and gel ink pencil on paper; 12 x 9 inches (paper)

Toyin Ojih Odutola/Jack Shainman GallerySo, I decided, I’m going to draw famous white men so you recognize them a little bit, but then render their specialness null with my black ball point ink. And i'm going to call it the Treatment because that nullification is the exact same treatment that Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and all of these people were repeatedly and systematically subject to. It was also about the images they chose to depict them. Classic example being Trayvon in a hoodie. It was the most irresponsible thing you could put, a picture of a child in a hoodie. The boy died in a hoodie. It felt willful and intentional and a manipulation.

I did the same thing. I made decisions in how I chose the subject and how I chose to depict them. I presented them as a group and not as individuals. Not only was their specialness null with the drawing itself of each portrait, but in how they were all placed together. There’s no specialness when you’re the same. If that sameness overrides your individuality than what are you?

Unclaimed Estates, 2017. Pastel, charcoal and graphite on paper, 77 × 42 in.

Toyin Ojih Odutola/Jack Shainman GalleryHave you ever been attacked for your views by the media or on social media?

I’ve had some people try me unsuccessfully because they lack this idea of intelligence, which I value very highly. If you’re coming at me, its very apparent to me that you’re not using empathy or logic. Not logic in the sense of some libertarian Pepe, but logic in the sense of where you are positioned in this conversation. So before you come at me, are you aware of where you are coming from? Most people are oblivious to that and those are the voices that get the most attention; the most outrageous and over the top voices.

There are people who felt like the last eight years were really hard on them. They felt abandoned and are justified in feeling that way. However, that does not give them mandate to harm people or bully them or be cruel. The thing that’s so ironic about this current right wing conservative or extremist time that we are in, is that they won, and yet they are still acting like they are the losers. They are still acting like we are on top for some reason. You have the guy you voted for, you have Trump. You have his administration and his policy and yet we are still to be blame in this?

In some ways, isn’t Trump giving people in Middle America permission to act this way? He seems to support this extreme behavior?

Going back to the idea of rejecting utopia. It’s not even just middle or rural America, a huge majority of the people who voted for him were very wealthy and college educated. I don’t even know where this fringe base is coming from, but he is definitely mobilizing them, even though he doesn’t actually care about them in terms of policy. I think that they feel like they have a choice now through him. The only thing I could say about it as someone who grew up in Alabama, as someone who’s engaged with this behavior growing up, is that the majority of these people feel like they are missing out and the world is moving too fast and leaving them behind.

It’s tough to be someone in an industry that’s dead. It’s tough to be a person who lived in a certain way for a very long time and have benefited from that, but this global economy can no longer sustain them. Here’s my advice to middle America, look at immigrants. You can learn a lot from them. What you’re experiencing is the immigrant life. If it seems so hard for you maybe you just need to look at their lives and gather inspiration from them.

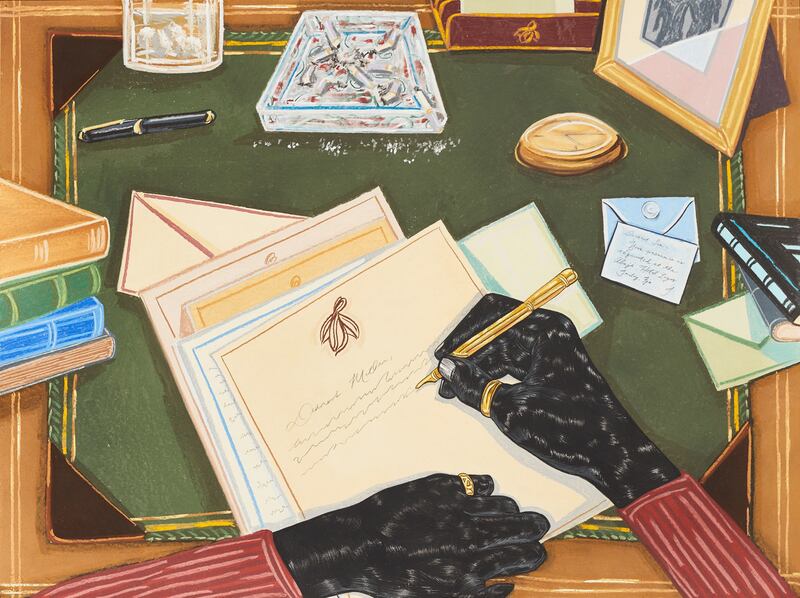

Winter Dispatch, 2016. Pastel, charcoal and graphite on paper, 29 1/4 × 39 1/2 in.

Toyin Ojih Odutola/Jack Shainman GalleryThe art market has long been associated with wealth and power. Owning art is somewhat of an elite status symbol. Are you impartial to the business side of art when creating your work?

I have no interest in it. It’s strange, this idea of bidding on culture. You must be really wealthy to see this as a sport. For the rest of us, this is our life. For me, art has always been a beautiful act of understanding the world and creating it at the same time. People see art as an exclusive club, but this club was not made for people like me. Somehow, I got my way into it and I am very blessed and grateful for it.

At the end of the day, I have no illusions about what I do in my studio. I am not here to entertain wealthy people or oligarchs. I am here to create an emancipatory space for people. Look, every day we gotta deal with bills, politics, pain and a lot of anger. If someone could walk into my Whitney show and see my pictures and feel good in any way, it’s really powerful. At the Whitney, I was with a group of kids from a school. They saw me doing a walk through and they were like “Are you the artist?” And they just lost it. They were asking all this stuff about how I draw.

You could just see it in their eyes that their brains were expanding. The possibilities were being made for them. That is a powerful thing. It’s not about the auction stuff. These things mean nothing, because those kids saw possibility in my work and it transmitted to them. I was damn near tears.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

To Wander Determined is now on display at the Whitney through Feb 25.