When State Department inspector general Steve Linick was abruptly fired, one of the inquiries he was conducting concerned a massive, highly controversial weapons sale to Saudi Arabia. Now the Trump administration is preparing to sell Riyadh even more weapons, The Daily Beast has learned.

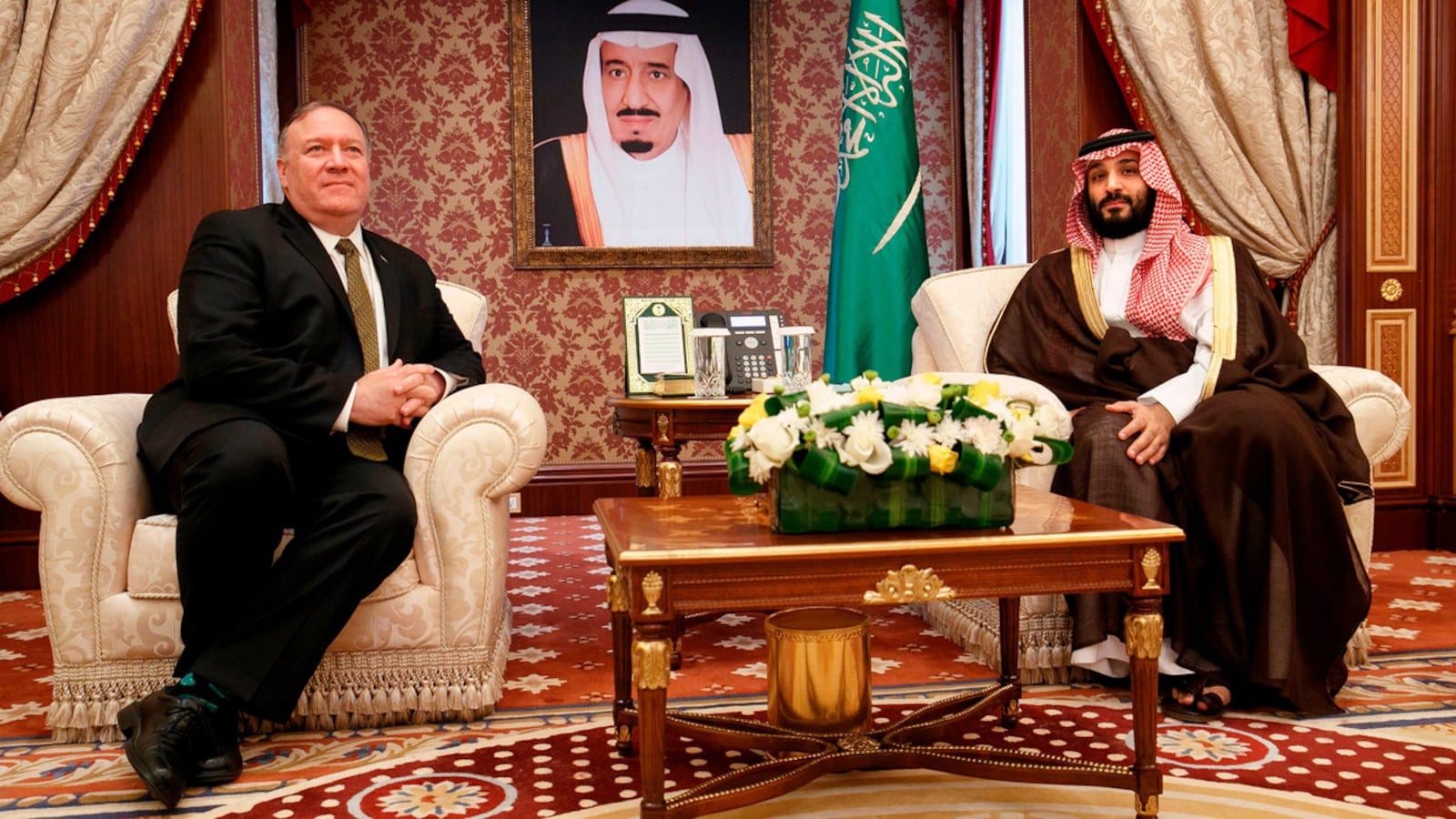

Two individuals familiar with the situation, including one with direct knowledge, said the Trump administration is drafting another request for a significantly smaller package of arms that includes precision-guided munitions similar to those Secretary of State Mike Pompeo approved in a highly contentious $8 billion sale in 2019.

Congress voted to condemn that sale, and is likely to strongly push back against a new one, too. The proposed sale comes less than two weeks after President Donald Trump fired Linick.

The prospective sale also demonstrates the entrenchment of the Trump administration’s bond with Saudi Arabia, right as Riyadh’s punishing war in Yemen and the grisly murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi has severely eroded Congress’ trust in the Saudis.

According to those sources, Saudi representatives have been pushing for a second arms deal for months now. That effort intensified in April when, in the midst of an already tanking U.S. economy as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, President Trump grew angry with the Saudi government over its oil-price war with Russia. According to a Reuters report, this included Trump teasing a threat to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that the U.S. may pull troops from the kingdom, if the price war were to continue.

In the top echelons of the West Wing, these sources said, Trump lieutenants who’ve advocated for further arms shipments to Saudi Arabia have included Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law and a close ally of the crown prince, and Peter Navarro, Trump’s trade adviser and one of the White House’s more prominent China hawks. As The New York Times reported earlier this month, Navarro and Trump have for years viewed these types of arms agreements with the Saudi regime as a boon for American jobs, even when those weapons are used for widely condemned mass slaughter.

The White House and the State Department did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Following the publishing of this report, CNN published an op-ed by Sen. Robert Menendez (D-NJ) confirming the Trump administration’s plans. “I am particularly troubled that the State Department has again refused to explain the need to sell thousands more bombs to Saudi Arabia on top of the thousands that have yet to be delivered from last year’s ‘emergency,’” Menendez wrote. “The secretary of state needs to answer our questions.”

Selling precision-guided munitions—missiles and bombs equipped with GPS to hit a specific target—also carries potential legal liability for U.S. personnel. A memorandum prepared by the State Department’s legal team in 2016 warned that aid to the Saudis for the Yemen war could open U.S. officials up to war crimes charges.

According to a U.S. official familiar with the memo, the inspector general’s office was in possession of that document ahead of Linick’s firing. A spokesperson for the State Department inspector general didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The U.S. official said the memo addressed concerns about American contributions to the Saudi-led war in Yemen, a conflict now five years old, and focused on law-of-war violations committed by the U.S. ally. Saudi warplanes over Yemen have destroyed hospitals and buses full of children; devastated civilian life; and yielded one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters. Congress voted to end U.S. involvement in the war, only to be overridden by Trump.

The memo warns that the Saudis’ use of U.S. munitions for their punishing air war, a practice the Obama administration began, increases the legal liability of U.S. officials for Saudi violations of the law of armed conflict.

Congress had made its objections known to last year’s $8 billion arms sale before it occurred. But Pompeo, on May 24, 2019, invoked an emergency authorization circumventing legislators—one that, Politico reported, prompted administration officials to object internally that they lacked an actual emergency from Iran. The sale prompted the Senate to pass bipartisan resolutions intending to restrict such arms deals. Menendez, working through the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, put together 22 resolutions of disapproval, and enlisted GOP support from such colleagues as Lindsey Graham (R-SC), Rand Paul (R-KY), Mike Lee (R-UT) and others. Trump vetoed the resolutions.

At a hearing with the State Department’s senior political-military affairs official the following month, Rep. Ted Lieu (D-CA) described the memo as a warning against “possible war crimes that the U.S. may be involved in.” The senior State official, R. Clarke Cooper, denied knowledge of the memo and didn’t commit to providing Lieu with the legal guidance his office received before the sale.

It appears the new round of arms sales comes outside Pompeo’s 2019 emergency authorization. At that time, Pompeo pointed to Iran’s arming of insurgents in Yemen and their use of Iranian ballistic missiles against targets in Saudi Arabia to justify the declaration of an emergency. The most recent attempt at a Saudi sale, however, comes amidst a period of relative calm on those fronts. UN Yemen envoy Martin Griffiths cited “significant progress” towards a comprehensive ceasefire between the Saudi-led coalition and Houthi insurgents. In May, the Defense Department announced it would withdraw U.S. troops and missile defense systems rushed into Saudi Arabia as tensions with Iran mounted starting in the summer of 2019.

According to a source close to the Saudi royal family, Riyadh is in talks with China to supply precision-guided munitions and other weapons. It represents a recognition that the Saudi reputation has cratered in Congress, no matter how solid the royals’ relationship with the Trump administration is. As well, the Saudis desire to manufacture sophisticated weaponry themselves, and China, unlike the U.S., is considered open to a technological transfer.

The push for the original $8 billion sale started under former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Tillerson was working with Brian Hook, now the administration’s top Iran hand, to figure out a way to push through the deal while maintaining a relationship with Congress, particularly the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, according to current and former officials familiar with Saudi arms sales who spoke with The Daily Beast.

Sen. Menendez in 2018 put a hold on the administration’s request to sell Saudi the arms. Hook and Tillerson were wary of moving too quickly on the sale because the department wanted to use the hold as a way to convince Riyadh to work with the Qataris on mending the Gulf rift, two former senior administration officials said.

But under increasing pressure from the White House, including from the president himself, his son-in-law Jared Kushner, and advisor Peter Navarro, the department in 2019 finally pushed forward with a plan to sell the arms to Riyadh. What surprised those working on the deal was Pompeo’s decision to move to sell under the emergency authorization.

“It went against the traditional norms of how the department normally worked with Congress,” one official told The Daily Beast. “The department could have just blown through the hold and gone ahead with the sale. But then there was this weird authorization that didn’t make a lot of sense to those involved.”

Pompeo provided Linick with written answers on the OIG’s investigation into the department’s workaround, but it is still unclear exactly what the office had found in its review of the $8 billion sale.

Sources inside the State Department and individuals familiar with the department’s IG office said Linick was unlikely to produce a report that would condemn Pompeo or his senior staff directly. One former official said Linick’s team was not known for aggressively pursuing investigations that could have a lasting, consequential impact on the secretary or the department as whole.

Two other senior administration officials said Linick’s ousting was just another example of Team Trump ousting former Obama administration officials—particularly inspectors general. Both said they were not convinced that Linick’s removal was anything other than Pompeo getting rid of an official the White House viewed as a potential threat, or, as one White House official characterized it, an Obama-era holdover who “should’ve been gone a long time ago.” (This official also cited former President Ronald Reagan’s controversial purge of IGs upon entering office in 1981 as an “appropriate model.”)

“I really don’t understand the connection here,” one of the administration officials told The Daily Beast. “Linick was looking into some stuff on Pompeo, for sure. But that wasn’t something that I saw the seventh floor fret about on a daily basis. The entire team in the department knew where Linick stood and what the office could and would pursue. It’s not clear that anything would have come out of those probes.”