KYIV, Ukraine—Such is the swamp of corruption in Ukraine that Donald Trump and Rudy Giuliani, in their many dealings with its businessmen, have been only one degree of separation from what’s generally called the Russian Mob. Or maybe less. And that’s not new. It goes back decades, to Trump’s years as a real-estate developer and Giuliani’s campaigns for mayor of New York City.

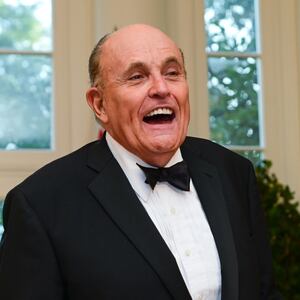

Now that Trump is president, with Giuliani acting as his lawyer and shadow envoy to Ukraine to try to dig up dirt on Democratic rivals past and present—an effort leading to alleged abuse of the president’s office and impeachment proceedings in the House of Representatives—those shady connections take on a whole new significance.

One of the central figures in the Trump-Giuliani-Ukraine nexus is Sam Kislin, a businessman and philanthropist often identified with the Russian émigré community of Brighton Beach in Brooklyn—and with alleged mob connections.

On Monday, the three House committees pursuing the impeachment inquiry sent a “request” to Kislin for a potentially vast trove of documents and communications with Trump, Giuliani, and scores of Ukrainians.

Kislin was not immediately available for comment.

Giuliani responded to a text message: "You are investigating people who may or may not have contributed to me 20 years ago." In fact, the contributions to his campaigns are a matter of public record. Giuliani suggested this line of inquiry is in itself some kind of coverup. "Why not focus on Biden’s shocking pay to play scheme, not how I uncovered it," he asked. "You should applaud my getting these serious allegations attention."

The supposed corruption allegations Giuliani has been making against Joe Biden and his son Hunter have not been substantiated by Ukrainian officials, although some in the Kislin circle might like to help make the case.

At the heart of the current impeachment inquiry is Trump’s none-too-subtle bullying of Ukraine’s recently elected President Volodymyr Zelensky in a July 25 phone call as exposed by a so-far anonymous whistleblower and partial notes on the conversation released by the White House.

Trump has described the call as completely ordinary and indeed “perfect”—which suggests the president of the United States is oblivious to his own accustomed mob-speak. Ukraine’s survival against Russian aggression was at stake, Trump had withheld vital aid, and when it was mentioned by Zelensky, Trump asked for “a favor”—the dirt he longs for on Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden. The exchange reads like a geopolitical version of the old protection racket threat: “Nice shop you got here, too bad if something happened to it.”

Although recently published narratives in the New York Times and elsewhere about developments over the last few months name several Ukrainian businessmen as intermediaries in Giuliani’s efforts to slime Clinton and Biden, for anti-corruption activists here the first local figure that leaps to mind in connection with Trump and Giuliani is 84-year-old Sam Kislin.

He has introduced himself to Ukrainian journalists as “Giuliani’s ex-adviser” and bragged of his donations to Giuliani’s mayoral campaigns in the 1990s. Kislin and Trump have been photographed together, and in the late 1990s Kislin reportedly played a small but crucial role helping Trump stave off financial disaster.

Kislin’s alleged ties to major figures in the Russian mob have been widely written about and only partially denied—an issue we will explore here at some length. He reportedly has been investigated by the FBI, but he has never been charged with any crime in the United States.

Two years ago the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU), citing as its motive “defense of economic interests,” barred Kislin from entering the country, a decision reversed in the courts since Zelensky became president last May. Kislin showed up soon afterward, telling local reporters he intended to testify against former President Petro Poroshenko.

Certainly if Trump or Giuliani needed a tour guide to the vast mire of Ukraine’s corruption, few know more about it than Kislin, who is currently caught up in a contentious fight to recover some $23 million he claims was stolen from him by Zelensky’s predecessor.

“I have come across such schemes! I can see everything,” Kislin told investigators from the Stop Corruption website. “Nobody needs to tell me anything, I can read by the eyes, I can read the lips, how people behave themselves here. It is time to become civilized.”

“Sam” Kislin was born Semyon Kislin in the Black Sea port of Odessa in 1935, but built his fortune out of the “Little Odessa” neighborhood around Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach. Kislin emigrated from what was then the Soviet Union in 1972 and, according to a brief biographical sketch on his website, first went to Boston, where he “found work at various jobs to support his family, including a grocery clerk and taxi cab driver.”

In 1976 Kislin moved to Brooklyn where “with the assistance of fellow Russian émigrés, Mr. Kislin established a small electronics store, where he sold goods to local residents.” Many of those residents were shipping or carrying appliances back to the USSR. Kislin writes that he “began trading goods with the former Soviet Union and, in time, became well respected in the international business community.”

It was right at the beginning of his Brooklyn career that Kislin made the acquaintance of a brash young real estate developer named Donald Trump who, Kislin subsequently told Bloomberg Businessweek, bought 200 televisions on credit for one of his Hyatt hotel projects. Kislin said that Trump paid him in full after precisely 30 days. “He never gave me any trouble,” Kislin said.

A much more important connection came years later.

In 1992, according to his website biography, Kislin “established Trans Commodities, Inc., which he ultimately developed into one of the world’s premiere commodities trading firms.”

Remember, in 1992 the Soviet Union had just collapsed and many billionaires were created almost overnight by looting the resources of the defunct communist empire. The lines between shrewd business dealings and organized crime were difficult to draw, including in Little Odessa.

“Look, back in the day it was impossible not to be connected to criminals,” Leonid Nor, vice president of the Odessan diaspora office in Brighton Beach, told The Daily Beast earlier this month.

In at least one instance, Kislin helped newly minted billionaires from the defunct USSR find useful places to put their money. Not in commodities but in luxury apartments.

Real estate was a favorite safe haven for fugitive Russian monies since they could convert mountains of cash into opulent residential addresses with few reporting requirements.

Nobody understood that better than Donald Trump, who had been cultivating Russian and other ex-Soviet clients from the beginning. But in 1998 he was struggling to survive. His casino and resort operations in Atlantic City were in deep trouble, and to recover he had to launch an enormous construction project—what would be at the time the world’s tallest all-residential building: Trump World Tower opposite the United Nations in New York. It was a huge gamble. Trump was under a mountain of debt to German banks. But the apartments were especially attractive to oligarchs who had just seen the ruble collapse and were rushing to get even more of their money out of Russia.

That’s where Kislin stepped in. As Bloomberg Businessweek reported, he offered his former Soviet compatriots personal mortgages, which presumably allowed them the time to move their money and, if they chose actually to be in New York, to live in over-the-top Trumpian luxury.

The 1990s also saw the flowering of Kislin’s relationship with Rudy Giuliani. As a matter of public record, when Giuliani ran for mayor in 1993 and then for re-election in 1997, Kislin, his family and companies contributed $46,250 to Giuliani’s campaign and organized fundraisers that garnered much more. Giuliani then appointed Kislin to the mayor’s Council of Economic Advisors, a position that Kislin still brags about.

In 1999, as Giuliani was about to launch his campaign against Hillary Clinton for the U.S. Senate in the 2000 election, Kislin reportedly co-chaired a fundraiser for him that racked up $2.1 million in contributions. But just then an investigation by the nonpartisan Center for Public Integrity made headlines: “Rudy Donor Linked To Russian Mob,” bannered the New York Post. Even The Moscow Times ran the Associated Press version of the story.

The Center for Public Integrity report noted that Kislin acknowledged “a business history with a reputed Soviet Bloc crime figure and a notorious arms dealer.” It cited a 1996 Interpol report that claimed Kislin’s Trans Commodities was “used by two reputed mobsters from Uzbekistan, Lev and Mikhail Chernoy, for fraud and embezzlement.” It stated that “a confidential 1994 FBI intelligence report on the Brooklyn, N.Y., mob organization headed by Vyacheslav Ivankov, the imprisoned godfather of Russian organized crime in the United States, lists Kislin as a ‘member/associate’ of Ivankov’s gang. It claims that his company co-sponsored a Russian crime boss and contract killer for a U.S. visa and asserts that he was a ‘close associate’ of the late notorious arms smuggler Babeck Seroush, who later settled in Russia.”

The report said both the FBI and Interpol concluded Trans Commodities had “laundered millions of dollars and was used for fraudulent banking documents by the Chernoys in the early 1990s as the brothers engineered the takeover of much of Russia’s metals industry, notably aluminum, through alleged embezzlement, money laundering and murder.”

(Chernoy had a long-running billion-dollar feud with Oleg Deripaska, another metals magnate once closely connected, as it happens, to former Trump campaign chairman and convicted felon Paul Manafort. Chernoy and Deripaska settled out of court in 2012 and just this year Deripaska, after U.S. sanctions against him were lifted, invested $200 million in a new aluminum plant in Kentucky, the home state of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. But that’s another story.)

Sam Kislin’s responses to the Center for Public Integrity were measured. “He acknowledged that Trans Commodities employed Mikhail Chernoy as the company’s manager between 1988 and 1992, but said he knew Lev Chernoy only in passing. ‘Mikhail Chernoy is the best man I ever knew,’ he said.”

Kislin said he didn’t know mob boss Ivankov. But, yes, he had done business with Seroush. That visa for a hit man? Someone had forged Kislin’s signature. And money laundering? “Never, never, never.”

Kislin reiterated that he has never been charged with a crime in the United States.

The most exhaustive investigation of Kislin and his family on the public record was conducted by the Massachusetts Gaming Commission in 2012 and 2013 when a company partly backed by Sam Kislin’s nephew, Arik Kislin, applied for a casino license.

The commission was far from satisfied with an investigative report supplied by Arik, which the commission suggested was “reverse due diligence” with “the intent of showing a clear record or history.” That report had claimed Sam and Arik did not work together and in fact Arik did not like his uncle very much. An investigator hired by the commission concluded Arik “was heavily involved in the business activities of his uncle Semyon (Sam) Kislin and his brothers.”

But even the favorable due diligence report had nuggets like this: “In 1992, [Arik] Kislin formed a company called Blonde Management. Kislin stated that the company was created for Chernoy’s convenience… Blonde Management periodically sponsored individuals for U.S. temporary work visas at Chernoy’s direction. There have been media reports that Blonde Management and Trans Commodities sponsored Anton Malevsky for a visa to enter the U.S. Malevsky was reputed to be a member of a Russian organized crime group and a contract killer. [Arik] Kislin acknowledged that, at Chernoy’s direction, Blonde Management submitted a work visa on Malevsky’s behalf.”

Malevsky died in a parachuting accident in South Africa in 2001.

The company backed by Arik Kislin did not get the gaming license in Massachusetts.

This background on Kislin is well known to independent corruption investigators in Ukraine.

The head of Transparency International in Kyiv, Andrii Borovyk, told The Daily Beast he is concerned about businessmen previously returning to Ukraine who previously were banned by law. “Kislin and his friends with dubious backgrounds helped Giuliani to get elected,” Borovyk said, adding, “Their activities should be a concern for any state.“

“We have questions for our authorities: what was Kislin doing in the offices of high [Ukrainian] officials?” Borovyk said he is “very worried” that former businessmen from the orbit of deposed pro-Putin President Viktor Yanukovych’s “who were previously accused of various violations here are now being permitted to come back to Ukraine.”

“We understand who Kislin is. He is considered to be a thief from New York, very well connected to organized crime,” Daria Kaleniuk, one of Ukraine’s most articulate corruption fighters, told The Daily Beast.

Kaleniuk’s watchdog organization, Ukraine’s Anti-Corruption Action Center, is keeping an eye on Kislin. “Kislin and a few other Giuliani clients, including Ukrainian billionaire Pavel Fuks, were buying Yanukovych’s toxic money; and Kislin wants his money back,” Kaleniuk said.

President Trump repeated several times at the press conference with President Zelensky that he knew many “very good Ukrainian people.” Perhaps he had in mind such men as Fuks and Kislin.

Certainly Kislin feels he’s got the backing of his powerful friends from New York City as he wages what sometimes sounds like a vendetta against the former head of state here. He accuses ex-President Petro Poroshenko of stealing not only his own money, but money supposed to have been part of a deal with the Trump administration. “Poroshenko cheated on my president, Donald Trump,” Kislin told the local press this summer. He claimed Poroshenko had promised to buy huge volumes of American coal, but did not, and in the process “stole $700-$800 million.”

The morass of corruption here is nothing if not complicated. Yuriy Lutsenko, the prosecutor Giuliani spoke with extensively about Joe Biden’s son Hunter, who was never accused of breaking any laws in Ukraine, is the same prosecutor who seized $1.5 billion held in Cyprus banks that Lutsenko said belonged to ex-President Yanukovych's "team," and Kislin now says belongs to him.

Back in Brighton Beach, meanwhile, it seems Trump and Giuliani can do no wrong. Leonid Nor, the vice president of the Odessan diaspora office, told The Daily Beast that when he’s visited Sam Kislin and his wife at their home, Kislin has talked about being “Trump’s old friend.” And that’s still a badge of honor. “We in our Odessa diaspora community all voted for Giuliani and for Trump,” says Nor. He says he even donated money for Trump’s border wall meant to keep out unwanted immigrants.

(Anna Nemtsova reported on this story from Kyiv.)