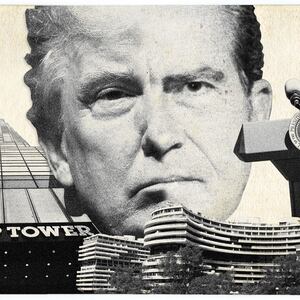

With every new question raised about the allegiances, motives and actions of Donald Trump in the first two years of his presidency, it is increasingly clear that the threats to the White House are following the pattern of those that gradually encircled Richard Nixon’s presidency.

Indeed it is striking how closely Nixon’s misdemeanors track those so frequently denied by Trump: the payment of hush money, the obstruction of justice, the suborning of perjury, the looming threat of impeachment and, enveloping the whole White House, the aroma of a cover-up.

Whether or not the BuzzFeed story about Michael Cohen and his testimony to Congress can actually support the fevered response it provoked, the fact is that the fired-up investigations by congressional committees under the control of Democrats will rip away two years of Republican obstruction and drive relentlessly toward the truth—independently of the Mueller investigation.

Although many of the details are different, the legal and procedural questions raised are not. Indeed, one common characteristic is how unresolved the answers to those questions still appear to be. For that reason, whatever the outcome, America now faces another ordeal of dangerous uncertainty.

That is why it is salutary to recall that Nixon’s effort to conceal and survive his role in the Watergate crimes and cover-up did not suddenly collapse: it spanned a long time – beginning in June 1972, and finally ending with his resignation on August 8, 1974. For most of that time Nixon believed he would survive – and he had good reason to.

To properly understand how this unfolded there is one uniquely compelling source – Nixon himself, as he struggled to defend himself in the final agonizing climax of his landmark television interviews with David Frost in 1977 – days of interrogation by Frost that were later immortally dramatized in a play and a movie.

What gives this account its special value is that it is not the detached view of historians or legal and constitutional authorities but of a president in the dock as Frost slowly turns the screw on him – Nixon suddenly playing his own defense lawyer who swings from being nakedly crooked to being remorseful and belatedly honest.

As Frost approached the final sessions with Nixon he had drawn up a list of those things that he felt he could prove that Nixon had either done, his crimes of commission or—equally damning—that he had not done, his crimes of omission.

It was to be a critical test for Frost himself because the U.S. networks regarded him as an outsider from Britain who had gatecrashed their turf to secure the interviews right under their noses. Although I was not on Frost’s team for these interviews, I had worked closely with him from his first steps in television journalism and, as he prepared for the Nixon interviews, he told me he knew how much was at stake for him. He had to deliver.

In fact, I had to explain to one member of his Nixon team that Frost rarely stuck to the chronology of prepared questions – like a nimble prosecutor he listened carefully to answers and pursued them even if it meant going into uncharted ground, a skill made more mysterious by the clipboard notes he always had on his lap with elaborate scribbles that nobody else could decipher.

To Frost the pivotal date was March 21, 1973 when Nixon, his chief of staff H.R. Haldeman and the chief White House counsel, John Dean entered into discussions that would turn out to provide some of the most incriminating evidence recorded on the White House tapes. Dean warned Nixon that Watergate had become “a cancer on the presidency” that unless it was cut out would destroy Nixon. He (correctly) predicted that several people, including himself, would likely end up in jail.

Frost and his team were armed with a depth of research on Watergate that neither Nixon nor his team anticipated. This was largely due to the work of James Reston Jr., one of the first researchers recruited to Frost’s team. Reston, the son of the legendary New York Times reporter, had performed a feat of diligence that remains a lesson for all journalists. He found scores of transcripts of the White House tapes that although seen by prosecutors had never been used in court but had remained – undetected by reporters – in the public record.

Using these transcripts Frost’s team was satisfied that they could prove that Nixon had personally directed a cover-up of the break-in of the Democratic National Committee offices at Watergate as early as June 23, 1972, when he asked the CIA to shut down the FBI investigation. But, instead of going back to June 1972 Frost set up a trap that anticipated Nixon’s version of the story by asking: “Now, you in fact, however, would say that your first learned of the cover-up on March 21. Is that right?”

On the March 21 tapes Nixon discussed the hush money that was being paid to Howard Hunt, the ex-CIA operative who had been one of the architects of the Watergate break-in and director of the so-called plumbers who carried it out (and a long-time dirty-tricks agent for the Republicans).

At first, Nixon lied outright. He distinguished between the cover-up and the hush money being paid to Hunt as a response to a threat from Hunt to go public: “I was first informed [on March 21] of the fact -the important fact to me in that conversation - of the blackmail threat that was being made by Howard Hunt, who was one of the Watergate participants. But not about Watergate.”

Nixon said he was worried that Hunt was a loose cannon – “I was very concerned about his emotional stability” and he didn’t know what Hunt knew or what he was threatening to do about it. He said it would have been wrong to pay off Hunt – “when it was given for the purpose of blackmail. In other words, hush money.”

(Hunt had asked for $120,000 and so far received $75,000.)

Frost then confronted Nixon with transcripts of Nixon discussing the payments with Dean and John Ehrlichman, White House chief domestic advisor. Nixon was taken aback by Frost’s detailed knowledge of the tapes. Rhetorically he asked “Why would you consider paying money to somebody who’s blackmailing the White House? I’ve tried to give you my reasons.”

“Why didn’t you stop it?” pressed Frost.

“…it’s a mistake that I didn’t stop it. The point that I make is that I did consider it.”

With the end of that day of interviews Nixon’s own staff were as rattled as he was – one of them said, “The president of the United States made himself look like a criminal defendant with David as prosecutor.”

Diane Sawyer, another staffer who was helping Nixon write his memoirs, said “He hasn’t written the Watergate part of his book yet, so none of us knew what he was going to say.”

Frost’s next day first target was obstruction of justice – at the last minute, just before the interview was to begin, Frost had received a copy of the statute defining the offense: “Whoever corruptly endeavors to prevent, obstruct or impede the administration of justice.”

The case for this went back to Nixon’s attempt to halt the FBI investigation in 1972, when he knew not only that Hunt had been involved but also the attorney general, John Mitchell.

Once Nixon realized that Frost was up to speed on the law he made a gymnastic move to argue that in this case it did not apply: “If a cover-up is for the purpose of covering up criminal activities it is illegal. If, however, a cover-up is for a motive that is not criminal that is something else again. And my motive was not criminal. I didn’t believe that we were covering any criminal activities.”

Frost insisted that even if the CIA had refused to go along with stopping the FBI investigation Nixon, in the very act of attempting to stop it, had obstructed justice because “it’s obstruction of justice if it’s for a minute or five minutes, much less for the period June 23 to July 5…”

Nixon: “The statute has the specific provision…one must corruptly impede a judicial…”

Frost: “A corrupt endeavor is enough.”

Nixon: “Conduct…all right…well...a corrupt intent, and that gets to the point of motive. One must have a corrupt motive. Now, I did not have a corrupt motive.”

After that session Frost commented to his team that in the response to a single question Nixon had denied the existence of a cover-up, admitted involvement in a cover-up, and defined the term cover-up in a way that no lawyer would ever define it.

As was becoming painfully clear to Nixon, Frost was using the transcripts of the White House tapes to devastating effect. And it was logical that Frost would then ask why those tapes had not been destroyed.

Nixon admitted that in April 1973 he had instructed Haldeman to search the tapes “to retain all those that had historical value and destroy those that had no historical value.”

After the March 21-22 conversations Dean had realized that Nixon was probably planning to set him up as a fall-guy and had decided secretly to cooperate with the staff of the senate special committee being led by the redoubtable Democratic Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina who styled himself as “a simple country lawyer.” This culminated with Dean’s sensational public testimony on June 25.

Responding to Frost, Nixon used Dean to explain why, after all, he did not destroy the tapes: “Dean had made some charges that I knew were untrue.” Haldeman, he said, had been wise not to destroy the system “because the tapes in many respects contradicted the charges that had been made by Mr. Dean.” (This was false, as Frost knew from the trove of transcripts he was using.)

Then, said Nixon, once the White House aide Alexander Butterfield revealed the existence of the tapes on July 16 he again considered destroying them before they could be subpoenaed by Ervin or the special prosecutor Archibald Cox. He didn’t because “it would have been an indication that I felt there were conversations on there that demonstrated that I was guilty.”

In October, the D.C. Court of Appeals ruled that Cox was entitled to the nine tapes he had subpoenaed. Nixon said that he again considered destroying them but it would have been an open admission that he was trying to cover something up.

Frost: “Looking back, don’t you wish you had destroyed them?”

“As a matter of fact, if the tapes had been destroyed, I believe it is likely I would not have had to go through the agony of the resignation” – but the discussions on the tapes had been “taken out of context” when he had, Nixon claimed, “been playing devil’s advocate.”

Going back to the tapes, Frost raised an issue that Rudy Giuliani has often raised in his manic dissertations on how Trump should respond to questions from the Mueller investigation, the risk of a perjury trap.

Frost raised the coaching that Nixon had offered Dean and Haldeman about giving testimony to a grand jury without falling into a perjury trap - Nixon had said perjury was “a tough rap to prove” and advised them “Just be damn sure you say, I don’t remember, I can’t recall.”

“Is that the sort of conversation that ought to have been going on in the Oval Office?” Frost asked.

“I think that kind of advice is proper advice,” replied Nixon, “I was beginning to put myself in the position of an attorney for the defense.”

Frost said that that sounded like citing faint recollection as a form of perjury, but Nixon responded that he wasn’t advising anyone to lie.

Nixon also admitted that he had considered and then rejected two steps to protect the conspirators: granting clemency and invoking executive privilege. In the case of executive privilege it would have included present and former members of his White House staff.

Frost moved on to a discussion between Nixon, Haldeman, Ehrlichman and Dean where they discussed issuing their own report on the cover-up. Ehrlichman had used a phrase that became a defining item in the Watergate vocabulary – that the report would be “a modified limited hangout.”

“You can’t have a limited version of the truth” Frost said.

(Rudy Giuliani has spoken of a similar stratagem for Trump’s response to the Mueller investigation.)

Nixon argued that a “limited” document did not mean that it was untruthful. He wanted to give his aides a chance to defend themselves. And then, astonishingly, he said that when he realized that by April 17, 1973, Dean had turned against him – “he was a loose can on the deck” – he had not used attorney-client privilege to shut him up. “I didn’t have to [drop the idea], but I did.”

Nixon had turned up late for this day’s interview, the only time he was late, and he was suddenly looking exhausted by the contest. But nobody foresaw that he was nearing the point of a shocking confession.

Sounding eerily like Trump, he clearly set out his own paranoia by listing the forces he saw arrayed against him: partisan media, a partisan Watergate congressional committee, a partisan special prosecutor’s staff and a partisan judiciary committee staff. For many months he was able to persuade himself that in spite of a cascade of evidence that he had been deeply involved in the cover-up he would not be impeached.

He had persisted in that belief, he said, because Vice President Gerald Ford had told him “We’re going to win by at least fifty votes in the House. We’ve got it made.”

Frost asked when he finally realized that the game was up.

“It was July 23, 1974” Nixon replied. “It occurred because the earlier rosy reports we had received from those keeping tabs on the House Judiciary Committee were proving unduly optimistic. The very shrewd and ruthless Tip O’Neill, now Speaker of the House, had put the screws to those Democrats who were leaning toward voting against impeachment.

“I did not commit, in my view, an impeachable offense. Ah, now, the House has ruled overwhelmingly that I did. Of course, that was only an indictment and would have to be tried in the Senate. I might have won; I might have lost. But even if I’d won in the Senate by a vote or two, I would have been crippled…in any event, for six months the country couldn’t afford having the president in the dock in the United States Senate.

“And there can never be an impeachment in the future of this country without a president voluntarily impeaching himself. I have impeached myself. That speaks for itself.”

Frost: “How do you mean, ‘I have impeached myself?’”

Nixon: “By resigning. That was a voluntary impeachment.”

“Now” he said, “under all these circumstances…I want to say right here and now, I said things that were not true. Most of them were fundamentally true on the big issues, but without going as far as I should have gone and saying, perhaps, that I had considered other things but not done them.”

Frost: “Well, you mean…”

Nixon: “And for all those things I have a very deep regret.”

Within a few minutes of that exchange Nixon reached the emotional depths of his confession and spoke the lines that made the Frost/Nixon encounter the epochal television event that it became:

“I let down my friends.

“I let down the country.

“I let down our system of government and the dreams of all these young people that ought to get into government but think it’s all too corrupt and the rest.”