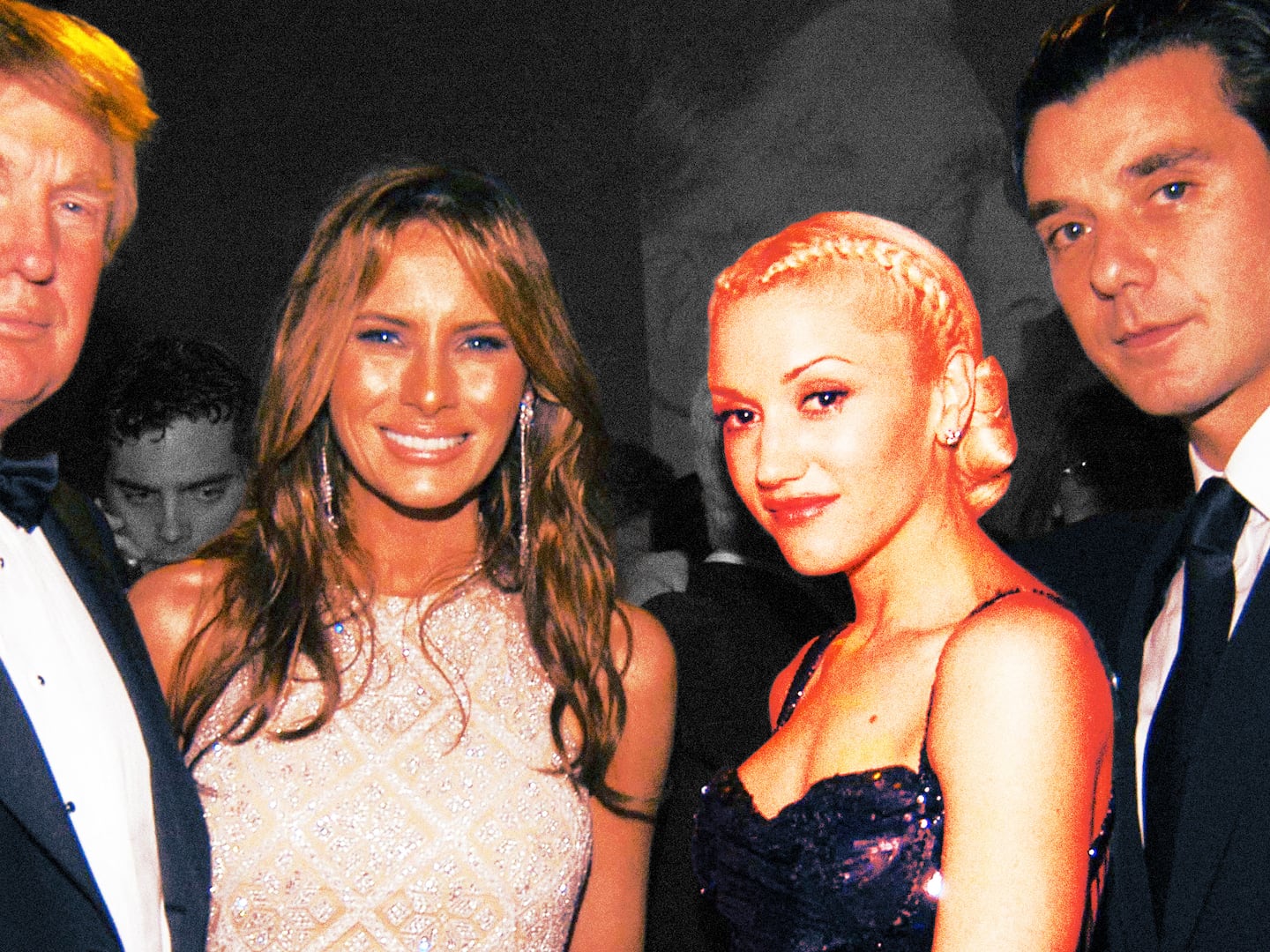

Trumpland

Leah Mills/Carlos Barria/Reuters

What’s Next in Trump’s Indictment: Can He Still Run? Will He Pardon Himself?

THE LOWDOWN

We answer all your burning questions on how Trump’s prosecution for hoarding classified documents could play out.

Trending Now