For years, a high-ranking accountant at the Trump Organization was the point man for ensuring that tweaked numbers padded Donald Trump’s wealth on paper.

But when he appeared on the witness stand at the former president’s bank fraud trial last week, the accountant’s supposed finance expertise suddenly vanished into thin air.

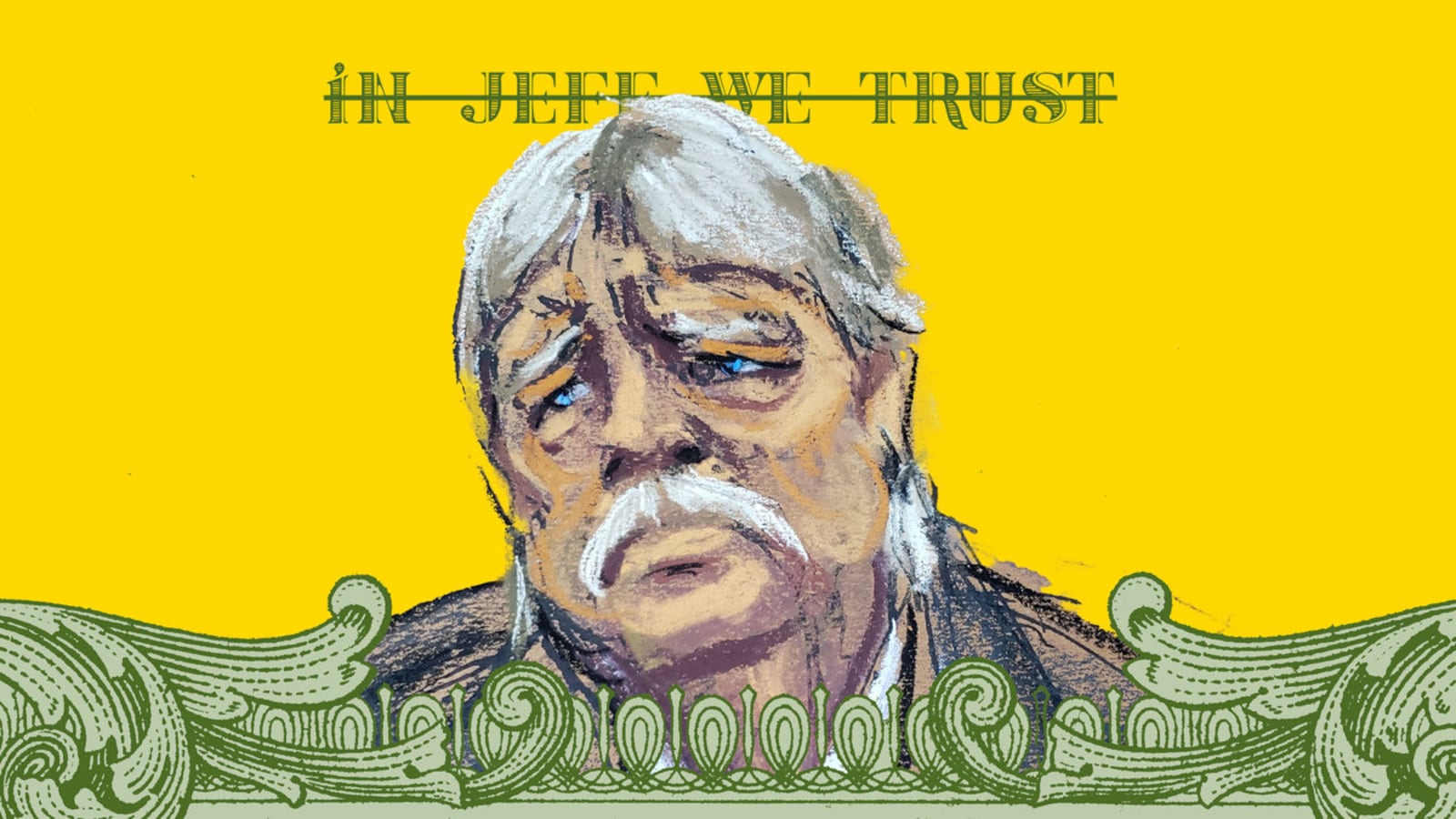

Jeffrey McConney, who recently retired as the company’s controller, has spent recent years facing close legal scrutiny.

In 2017, state investigators questioned him over the way Trump misused his charity, which was eventually dissolved. Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg used McConney’s testimony to convict the Trump Organization of tax fraud last year. And now, New York Attorney General Letitia James’ attorneys are trying to use McConney to prove that the Trump family committed bank fraud and should have their real estate empire revoked of its business licenses and potentially stripped of its assets.

Now, McConney is in a precarious position, because the attorney general’s law enforcement effort also targets him directly. Alongside his former boss, he is a defendant in James’ $250 million lawsuit, given that the accountant was the one who routinely tallied up the estimated values of dozens of Trump properties—many of which were deliberately pumped up.

McConney’s deep familiarity with the Trump Organization and its business strategies made it all the more astounding when, on Friday, Trump’s defense lawyers suddenly took the stance that McConney actually doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

The shocking moment happened when Andrew Amer, special litigation counsel for the attorney general, asked McConney about the way company documents seemed to fake the rent a high-end grocery chain paid at Trump’s building at 40 Wall Street in Manhattan.

“Can we agree, Mr. McConney, that by adding the income from the lease from Dean & DeLuca into your valuation that you double-counted the Dean & DeLuca income in your valuation?” Amer asked.

“Objection, Your Honor,” interjected defense lawyer Jesus Suarez. “Mr. McConney is not a valuation expert. He’s not offered as a valuation expert.”

New York Supreme Court Justice Arthur F. Engoron quickly overruled that objection, but the ridiculous dichotomy was not lost on those in the courtroom.

The idea that the Trump Organization’s long-time bean counter would be oblivious to the inner workings of real estate valuations seemed implausible, given that documents presented at trial showed that he was the key conduit to getting those very valuations compiled into Trump’s annual statements of financial condition.

That paperwork, which was signed off by outside accountants at the firm MazarsUSA, was the reason that financial institutions like Deutsche Bank and Ladder Capital extended hundreds of millions of dollars in loans to Trump. Those funds allowed his company to seal several marquee deals, including the purchase of the Doral golf course in South Florida and the acquisition of the Old Post Office in downtown Washington, which briefly became a Trump hotel.

The inherently contradictory nature of Trump lawyers’ stance on McConney underscored the sharp contrast on display at the ongoing bank fraud trial, where James is trying to bolster a case the judge has already decided has merit while Trump lawyers combat the very premise of the investigation. When investigators point to spreadsheets, the defense either shrugs, appears confused, or claims vastly inflated values are mere differences of opinion.

For days, state investigators have been laying out how the Trump Organization fudged its numbers before turning the books over to its outside accountant Donald Bender at MazarsUSA. There, the firm would sign off on Trump’s personal financial statements and give them the aura of authenticity. It was McConney’s job to prepare the spreadsheets that listed properties, associated bank account totals, and estimated values.

With him on the stand, the AG’s office reviewed the way McConney gathered real estate development valuations as part of his regular job as the company controller. They repeatedly pointed out how he appeared to use omissions to trick Mazars and throw them off the scent of any impropriety.

Take, for example, Trump Park Avenue, a residential building located in an ultra high-end area east of Manhattan’s Central Park. When McConney put together the numbers for the 32-story condo building, his original spreadsheet listed all the units, along with their offering prices and market values.

But McConney admitted to intentionally deleting that last column before sending it over to Mazars—ensuring the outside firm could only see the pie-in-the-sky prices Trump requested, not the market values that reflected what someone would actually pay for those luxury condos.

That sleight of hand added roughly $57 million to Trump’s wealth on paper, math that McConney acknowledged in court.

Then there’s the forested estate in upstate New York called Seven Springs, a failed development project that doubles as Trump’s Bruce Wayne-esque mansion just north of Gotham. Once again, McConney played a central role in fudging the numbers by acting as if seven additional mansions had been greenlit for construction, adding a whopping $161 million to the total value.

And once again, McConney copped to those calculations on the witness stand.

“Were you operating under the assumption when doing this valuation in these two years that approvals had been obtained, all necessarily approvals had been obtained for these seven homes in Bedford?” Amer asked him.

“Looking at this now, yes,” McConney responded.

Some of the dodgy math appeared to come from Eric Trump, one of the former president’s sons, who has long served on the Trump Organization’s leadership team. McConney testified that, after a telephone conversation with the Trump company executive in 2013, another section of Seven Springs jumped in value on paper from $25 million to $101 million—even though they couldn’t actually sell the property they claimed to have.

“And he also, by the way, told you that the project was put on hold, right?” Amer asked.

“Yes,” McConney said.

“But you’re still accounting for the profit from those 71 mid-rise units that were put on hold, as if it’s immediately realized as of June 30, 2013, correct?” Amer asked.

“Yes,” McConney responded.

At times, the ex-controller demurred, pointing out that, in fact, there was another department that was really in charge of coming up with asset values. But investigators kept displaying spreadsheets and emails that either bore McConney’s name or were created by him, highlighting his key role in making sure these numbers got in front of the right people to secure those bank loans.

On the stand, the accountant claimed to be oblivious to the basic facts about yet another dubious deal of Trump’s with regard to the Seven Springs property, even though it was his job as the company’s controller to oversee the Trump Organization’s books.

This one dealt with the way Trump eventually cut his losses at Seven Springs: by creating a conservation easement on the property, essentially giving up development rights by dedicating the land for natural preservation, in exchange for a tax break.

Though Trump stretched out the tax write-off beyond belief by inflating the land value there, McConney claimed he didn’t even understand what was going on.

“What’s being donated are the development rights, correct?” Amer asked.

“I’ll take your word for that,” McConney responded.

At the trial last week, McConney revealed that he recently retired from the Trump Organization and received just over half of his $500,000 severance package. The detail raised questions about his testimony that were reminiscent of the deal that his direct boss, Allen Weisselberg, got while he was testifying at the company’s criminal tax fraud trial last year.

Although the judge in the current civil trial has already determined that the Trumps, McConney, and Weisselberg engaged in bank fraud and that business licenses should be revoked, the Attorney General still has a long way to go before she can declare total victory. The trial is set to continue until the end of December