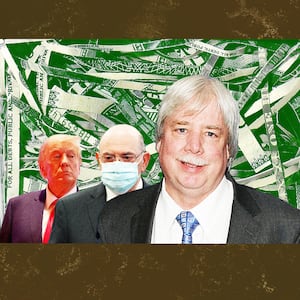

As the criminal tax fraud trial against former President Donald Trump’s private business comes to an end, one moment in court on Thursday summed up the absurdity of the Trump Organization’s defense strategy of blaming their problems on a chief financial officer gone rogue.

It came when prosecutors pointed out how outlandish it was for the company to scapegoat Allen Weisselberg after he pleaded guilty—even as it continues to pay him handsomely and its lawyers refer to him as a member of “the family.”

“You know what the most unusual thing in this case is? The same day he finalized the terms of the plea, he had a birthday party in Trump Tower! Maybe if he hadn’t agreed to testify against the Trump Organization, it would have been a bigger cake,” said Assistant District Attorney Joshua Steinglass.

As he spoke, some jurors couldn’t help but smile and hold back laughter.

The prosecutor’s comment touched on what turned out to be the trial’s most memorable surprise: that the same guy who was booted off the company’s many global executive boards had quietly returned as a family business adviser—and was getting paid the same $640,000 annual salary. On the witness stand last month, Weisselberg cheerfully admitted to eagerly expecting the same $500,000 yearly bonus.

“Here’s a question for you,” Steinglass told the jury. “Why do you think they didn’t fire him? Could it be so they could dangle that January bonus in front of him?”

Allen Weisselberg leaves the courtroom during a trial at the New York Supreme Court on November 17, 2022 in New York City.

Michael M Santiago/GettyThe Manhattan District Attorney’s Office is targeting the Trumps and their corporate empire, part of an investigation that began when Trump was in the White House and essentially beyond the reach of law enforcement. The elected DA Alvin Bragg, who assumed leadership of the office in January, was reluctant to bring a case against Trump himself—an embarrassing move that prompted top prosecutors to quit and threw the larger investigation into chaos. But the office continued a watered-down case against the CFO and the company.

Weisselberg pleaded guilty to tax fraud in August, and trial started in October. His guilty plea positioned him to be the star witness against the company, given that he understood how the books were tweaked to gift executives untaxed benefits. But he turned out to be a tepid witness, taking the fall all on his own.

That trial is now coming to a close. Jurors have learned how Trump Organization executives siphoned away some of their full-time salary and paid themselves as “independent contractors,” thus eliminating payroll taxes for the company and allowing themselves to dodge taxes too. They also heard about the way the company routinely showered its top executives with luxury cars, high-end Midtown apartments, and even a $6,000 no-show job for Weisselberg’s wife.

Attorneys began to deliver closing arguments on Thursday, and it’s possible jurors will start deliberating privately on Friday.

The 75-year-old former financial executive faces nearly four months at Rikers Island, a notorious city jail where the conditions have become so dire lately that there is a suicide crisis among desperate inmates.

The looming threat of time at Rikers was mentioned several times by Trump Organization’s lawyers on Thursday, as they tried to convince jurors that Weisselberg did everything he’s accused of doing—but he did it without tipping off the Trumps.

Susan Necheles, the Trump Corporation’s defense lawyer, kicked off with this line: “We are here today because of one reason and one reason only: the greed of Allen Weisselberg.”

“He dedicated his life to the Trump family. Over nearly 40 years of service to three generations, from Fred to Donald to Don Jr. and Eric, he helped grow the Trump Organization into the company it is today. But along the way, he messed up. He got greedy. And once he started, it was difficult for him to stop,” Necheles said. “No member of the Trump family knew about his ongoing efforts to evade taxes. He was ashamed of what he was doing. You saw him on the witness stand almost crying.”

Later in the day, a defense lawyer representing another indicted Trump corporate entity picked up where she left off. Michael van der Veen, an attorney for the Trump Payroll Corporation, relied on the Johnnie Cochran method, repeating a mantra that he hoped would echo in jurors’ brains.

O.J. Simpson had, “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.” The Trump Corporation has, “Weisselberg did it for Weisselberg.”

Allen Weisselberg at the hearing for the criminal case at the criminal court in lower Manhattan in New York on July 1, 2021.

Seth Wenig/Getty“This case is about greed, but only the greed of Allen Weisselberg. This is about individual, personal greed and the abuse of trust needed to feed that greed,” van der Veen said. “He only tried to improve his own economic condition and that of this wife and his children.

Prosecutors countered the “Weisselberg did it for Weisselberg” chant by pointing out how Weisselberg pulled this off with help from his direct report, company controller Jeffrey McConney. And how chief operating officer Matthew Calamari got similar benefits. And how a junior employee was told to delete the evidence just as Trump was realizing his political ambitions in 2016.

"Allen Weisselberg didn't steal from the company. He stole with the company. The Trump Corporation isn’t the victim in this," Steinglass said. "It's just plain silly."

Despite the overwhelming evidence of the rampant accounting games played at the former president’s family company, the trial could come down to the exact meaning of a highly technical and utterly awkward legal turn of phrase: whether Weisselberg and McConney acted “in behalf of” the company.

“In other words, with some intent to benefit the corporation,” as Necheles clarified in court on Thursday.

Necheles and van der Veen, defending two instances of the same company, spent hours trying to isolate Weisselberg as someone who acted for himself. But they also minimized the benefit experienced by the corporations. Van der Veen pointed out how the payroll entity saved roughly $25,000 in Medicare taxes—while paying its employees $267 million from the start of 2011 to the end of 2018.

Defense lawyers also stressed that Donald Trump’s decision to pay for Weisselberg’s grandkids’ expensive private school tuition was really a gift, not tax-free income—even though prosecutors had internal company documents where the accounting department specifically accounted for the tuition as part of the CFO’s salary.

“It’s literally a blueprint for fraud. It might as well be entitled, ‘How I Did It,’ by Jeffrey McConney,” said Steinglass. “You can’t say it’s not income when you’re tracking it as income… if McConney hadn’t been so brazen to put this in writing, who knows if this fraud would have ever been detected?”

Allen Weisselberg at the New York Supreme Court on November 17, 2022 in New York City.

Michael M Santiago/GettyThe Manhattan DA’s office used its closing arguments as an opportunity to finally address a burning question that has been posed by many of those observing the trial—why other executives weren’t criminally charged as well.

Trump Organization defense lawyers used that fact to undermine the strength of the overall investigation. But prosecutors acknowledged that there was simply less evidence for other executives, which would have made for weaker individual cases. They also admitted that they traded away the opportunity to prosecute key insiders because investigators needed to squeeze them for information—so they were offered immunity for testifying before the same grand jury that indicted the Trump companies and Weisselberg.

“The real shame here is that we had to call Jeffrey McConney before the grand jury to authenticate the documents,” Steinglass said. “It doesn’t matter they weren’t charged... what, because Allen Weisselberg had 10 grounds for fraud and they had one? The Trump Organization was in for all of it.”