When President Donald Trump announced his plan to restart his 2020 campaign rallies in Tulsa, Oklahoma on June 19, it was met with widespread disgust. Not only is the date he chose one that honors the freedom of all enslaved African Americans in the U.S., but the Juneteenth rally was to take place in a city that was home to what may have been the most brutal anti-Black slaughter in post-Civil War America, the Tulsa Race Massacre.

For once, even he couldn’t ignore the outrage and moved his event to the following day.

But even if his campaign had planned the rally out of ignorance, rather than malice, that only highlights how obscured this moment in American history has become in the century since, with even the official death count shrouded and questionable.

Nearly a century later, the violence against Black people continues. But countless video recordings in recent years and efforts at civilian record-keeping at least help ensure that heinous acts of brutality against Black people in America can never again be forgotten or sanitized.

The massacre took place 99 years ago this month, over an 18-hour time period starting on May 31, 1921, in the largely affluent and Black neighborhood of Greenwood—often referred to as Black Wall Street.

A wealthy Black man named O.W. Gurley purchased the land that would later become Greenwood, named after a town in Mississippi. Oklahoma, with its rich oil industry, attracted African Americans relocating after the Civil War to more than 50 new townships. Greenwood, a fairly self-sufficient neighborhood built “for Black people, by Black people” despite being under the crushing arm of Jim Crow, was booming with opportunities. There was even a belief that money would circulate “19 times” before it left Greenwood.

The town’s success also garnered the ire of white people who hated the idea of what they deemed to be an “inferior” race prospering in spite of all that was stacked against them. To make matters worse, nationwide, The Ku Klux Klan was back with a vengeance and during the Red Summer of 1919, anti-Black violence ran rampant around the country. In Tulsa, there was also a sense of lawlessness that led to vigilantes taking it upon themselves to play judge, jury, and executioner.

One day, a Black teenager named Dick Rowland was accused of assaulting a white elevator operator named Sarah Page (a situation we’ve seen proven false before). Whatever happened inside the elevator, Sarah ran out screaming. Though it’s been suggested that he may have simply stepped on her foot, Rowland was arrested and, after the Tulsa Tribune called it an attempted rape the next day, white people formed an angry mob at the courthouse. Several eyewitnesses recalled the paper also publishing an editorial, “To Lynch Negro Tonight." That editorial, if it existed, was lost to history at some point.

As threats to Black Oklahomans increased, The Tulsa Star, the largest Black paper in the state at the time and “An Uncompromising Defender of the Colored Race,” had encouraged Black men to arm themselves for protection, and, with talk of a lynching circulating, a group of armed men went to the courthouse to protect Rowland. After they left, another rumor circulated that white people were storming the courthouse, and a second group of about 75 Black men returned, facing off with 1,500 white men. After a shot was fired, the chaos began.

The white mob, itching to see a Black man get lynched, ended up disappointed. So they wreaked havoc on the town. There were drive-by shootings and a Black man was murdered in a theater. There were even witnesses reporting multiple planes flying low and dropping bombs. That would mean African Americans experienced terror from planes 80 years before 9/11 and an air assault on American soil 20 years before Pearl Harbor.

The mob looted buildings, killed dozens of people, and essentially burned down the area of 36 city blocks. Thousands were left homeless and the businesses that helped bolster “Black Wall Street,” including The Tulsa Star, were destroyed or shuttered.

The police were of little help to the Black victims and those who fought back during this harrowing invasion. An eyewitness said that after deputizing a lynch mob, officers instructed the group to "get a gun and get a n*****."

Firefighters who tried to extinguish the flames were threatened by the mob and then stopped putting out the fires.

It was also reported on June 1, 1921, that the National Guard had used machine guns on a group of African Americans, killing “half a hundred.” The National Guard, called in to end the massacre, denied this.

The most high-profile murder was that of Dr. A.C. Jackson, who stepped out of his home with his hands in the air and said “Here am I. I want to go with you,” according to his neighbor. Dr. Jackson was then shot with “a high-powered rifle.” The neighbor claimed he “recognized one of the men as a former or current Tulsa police officer.”

No charges were filed in the death of Dr. Jackson, and only a handful of people were even charged with things like looting and arson. Insurance claims for at least $25 million in today’s dollars were mostly rejected, since policies had an exemption for riots.

Most of the Black population of Tulsa was left homeless as thousands of African Americans were placed in “protective custody” or in camps during the riot and some were held for days or weeks afterward.

For years after, there was an effort to cover up what happened and the event was rarely spoken of in formal or official settings. It wasn’t until this February that Oklahoma’s Education Department announced the Tulsa Race Massacre would be taught in public schools.

The exact number of deaths is also unknown. Directly afterward, The Tulsa World reported about 100 deaths, while The Tulsa Tribune (which treated two dead white men the next day as the banner news) reported 77, and so on.

The bodies were not dealt with in a conventional manner. Major Byron Kirkpatrick, a Tulsa attorney on the staff of Adjutant General Charles Barrett, who led the National Guard’s response to the riots, did not know where the bodies were taken, reported The Tribune, “whether they were placed at some specific point for later attention, if they were dumped into a large hole, or thrown into the Arkansas river.”

Eventually, death certificates were written for 37 people, 25 Black males including nine nameless victims burned beyond recognition and 12 white males.

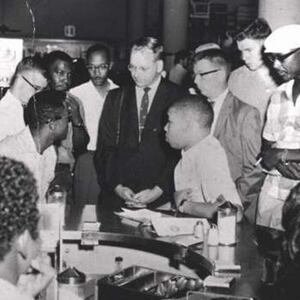

Library of Congress

Library of CongressTwenty years ago, the number of verified deaths was 39 according to the Tulsa Race Riot Commission. As of February, efforts to find the unnamed and uncounted bodies in suspected mass graves are still underway, with a test excavation scheduled for July.

The Commission, formed in 2000, eventually recommended reparations for victims of the massacre and their survivors. But the city opposed that, and the state issued decorative medals instead.

As the lawyer representing the massacre’s last living survivor, Lessie Benningfield Randle, wrote last week, “for the African American community, the Greenwood massacre isn’t just history — it is felt to this day.” Randle remembers fleeing her grandmother’s house as a little girl and “seeing bodies in the street” as white people were “trying to kill all the Black men.”

The same week that article appeared, the city released a video showing Black teens being roughly arrested for jaywalking, and a high-ranking police official said in an interview that “we’re shooting African Americans about 24 percent less than we probably ought to be based on the crimes being committed.”

While Trump’s trip has brought renewed attention, the massacre has never received the nation-wide awareness we are seeing for the tragic death of George Floyd, a Black man who was killed as a white police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes, because racist gate keepers wanted it that way.

Like the shady police practices that go on when it’s assumed no one’s watching, America could see another Tulsa through the countless lives lost to both police brutality, and anti-Black violence at large.

In the case of Breonna Taylor, a Black woman killed as she slept during a no-knock invasion, police involved in her death listed the number of injuries as “none” and checked “no” next to “forced entry,” verifiably false information. And Much of their report was simply left blank.

From Eric Garner, to Walter Scott, to Philando Castille, to George Floyd, and now Rayshard Brooks, the power to document and report is in the hands of everyday civilians. The movement we are seeing today is because Floyd’s tragic death was recorded by people who are sick of letting these events go unnoticed, or be self-reported and unchecked by the perpetrators themselves.

The Derek Chauvins of the world can no longer move about life freely and with a history of complaints without the threat of one more wrong move leading to a total public ousting.

While we’re at it, we aren’t letting the “Karen” Coopers and Barbeque Beckys get away with their manufactured white tears as they attempt to throw away the lives of Black people either.

Tulsa was a lesson in what happens when we allow the oppressors to be the documentarians.

We often hear that history is told by the winners. Looks like we’re going for the gold.