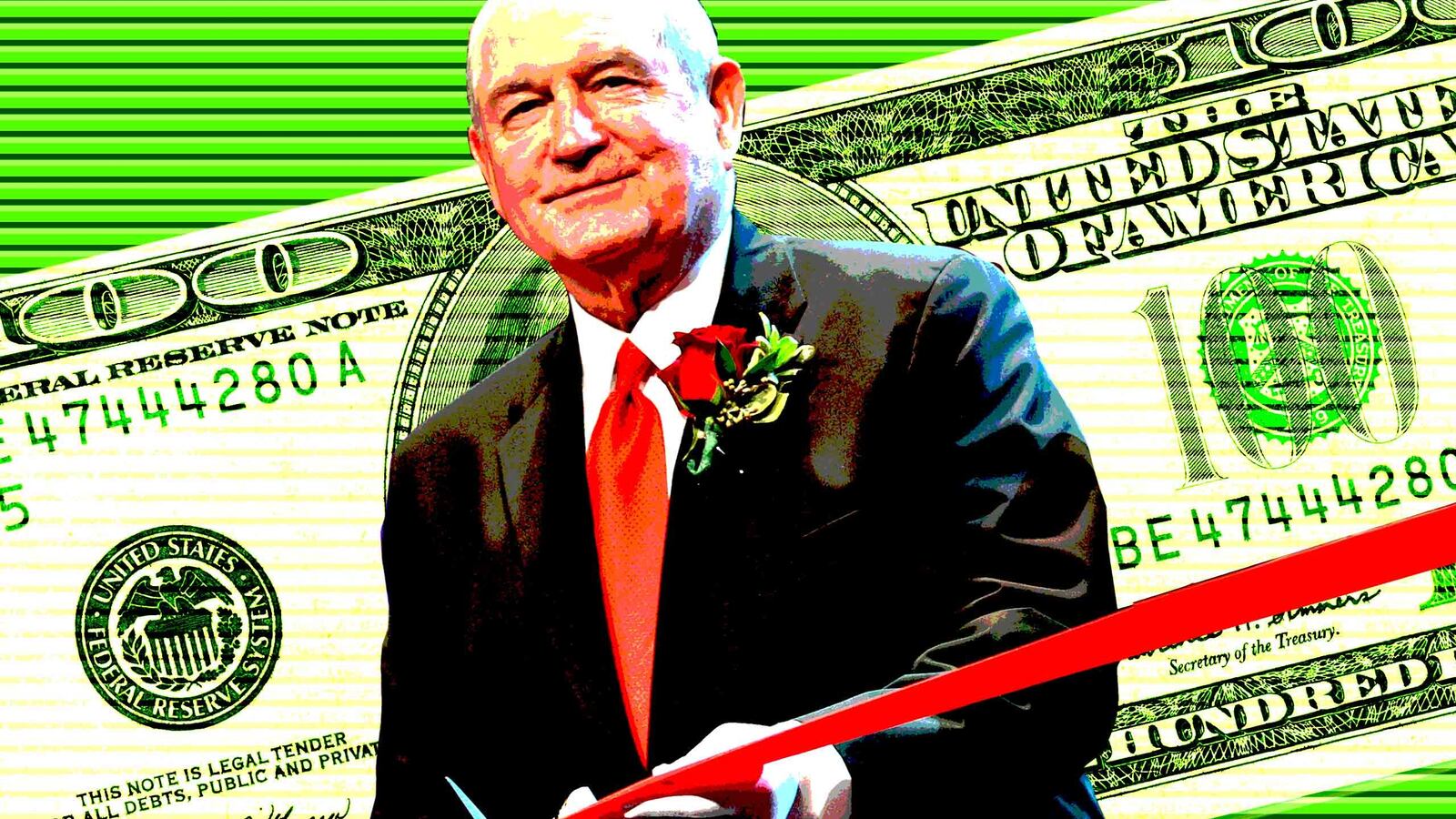

Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the Department of Agriculture has pledged to restructure his assets to avoid conflicts of interest, but public records show he has already benefitted financially from a major Trump administration policy.

Agriculture Secretary nominee Sonny Perdue, the former Republican governor of Georgia, owns a grain merchandising company that, along with a trade association directed by Perdue, fought an Obama administration environmental rule that the company expected to increase its regulatory compliance burden and reduce the value of its land holdings.

In late February, President Donald Trump announced that he was rolling back the regulation, known as the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) rule. In remarks on the executive action, Trump noted that WOTUS was “one of the rules most strongly opposed by farmers, ranchers and agricultural workers all across our land.”

Among those workers were the employees of AGrowStar LLC, a company owned by Perdue and his wife that bills itself as “a full service grain merchandising company offering solutions for all sizes of clients and customers.”

AGrowStar officially lent its support to a lawsuit in 2015 challenging the WOTUS rule. In a joint filing with a Georgia-based fertilizer company, AGrowStar told the court that they “are engaged in operations or own properties affected by the WOTUS Rule” and would be “harmed by the WOTUS Rule to the extent they must either comply with the rule or suffer penalties or because their properties or businesses are devalued by the rule’s requirements.”

But Perdue was not simply another plaintiff in the suit; he was involved personally, through AGrowStar, and by way of an agribusiness interest group.

On its website, the Southeastern Legal Foundation said it brought the lawsuit on behalf of Perdue “and other companies and organizations.”

Perdue represents AGrowStar on the board of one of those other organizations, the Georgia Agribusiness Council, which officially joined SLF in pushing the court to overturn the rule.

When AGrowStar filed a motion to intervene in the suit, it noted that it would be represented by SLF’s attorneys. The same attorneys represented the GAC.

The lawsuit was pending before a federal appeals court when Trump rescinded the WOTUS rule. AGrowStar, which was fined in 2012 for “serious violations” of federal workplace safety laws, will no longer have to worry about the rule’s financial burdens.

That is good news for Perdue, who reported an ownership stake in AGrowStar worth between $5 million and $25 million in a personal financial disclosure statement filed on Friday with the Office of Government Ethics (PDF).

The company is technically a subsidiary of Perdue Business Holdings, Inc., a holding company owned by two trusts set up for the benefit of Perdue and his wife and children. Perdue Business Holdings also owns ProAg Products LLC, a grain market trading company.

Perdue’s involvement in agribusiness by way of AGrowStar and ProAg could present conflicts of interest if he is confirmed. He told OGE last week that within 90 days of his confirmation he will place Perdue Business Holdings and its subsidiary companies into a new trust “that will not benefit me or my spouse” (PDF).

He did not rule out keeping his children as the beneficiaries of that new trust. A spokesperson for the Trump transition team, which is handling media requests for the president’s nominees, did not respond to questions about the trust’s structure.

Perdue had previously been dismissive of blind trusts, which keep officials in the dark about how their money is invested, as a means of preventing conflicts of interest. “A blind trust is not functional for a small business person,” he said in 2006 in the face of ethical scrutiny. “I’m in the agri-business. That’s about as blind a trust as you can get. We trust in the Lord for rain and many other things.”

Perdue told OGE that he is expecting to personally bring in additional income from AGrowStar even if confirmed, and has been earning interest on that outstanding payment. The payment will eventually come by way of the new trust he is setting up to take ownership of the company, he wrote.

According to Perdue’s financial disclosure statement, that “promissory note” is worth between $500,000 and $1 million, and Perdue earned between $50,000 and $100,000 in interest on the obligation last year.

“Until this promissory note has been repaid in full, I will not participate personally and substantially in any particular matter that to my knowledge has a direct and predictable effect on the ability or willingness of AGrowStar, LLC... to repay this note, unless I first obtain a written waiver,” Perdue told OGE.

Perdue’s continued financial ties to companies that could be affected by USDA rules, and in AGrowStar’s case one that already benefitted from administration policy, could revive ethics controversies from Perdue’s time as governor during his confirmation hearings.

He faced 13 ethics complaints during his tenure as governor, and was twice found to have violated state ethics rules, issues sure to be raised by Democrats on the Senate Agriculture Committee.

Those controversies included allegations of cronyism involving AGrowStar. In 2003, Perdue appointed the company’s president to a state agriculture post. The governor later promoted AGrowStar, which he had purchased a few years earlier, in official public remarks.