Now that the jury has delivered a decisive and unanimous decision, finding Donald J. Trump guilty on 34 felony counts in his New York hush money case, the question turns to how he will handle the conviction. He has spent much of the trial trashing the legal system, bemoaning himself as a victim of its unfairness, has targeted the judge relentlessly, and behaved like a contemptuous brat. The Constitution says no-one is above the law; Trump has been clear—in his view, this does not apply to him.

Already, Trump is working to delegitimize this decision. “This was a disgrace,” Trump said after the trial. “This was a rigged trial by a conflicted judge who was corrupt.”

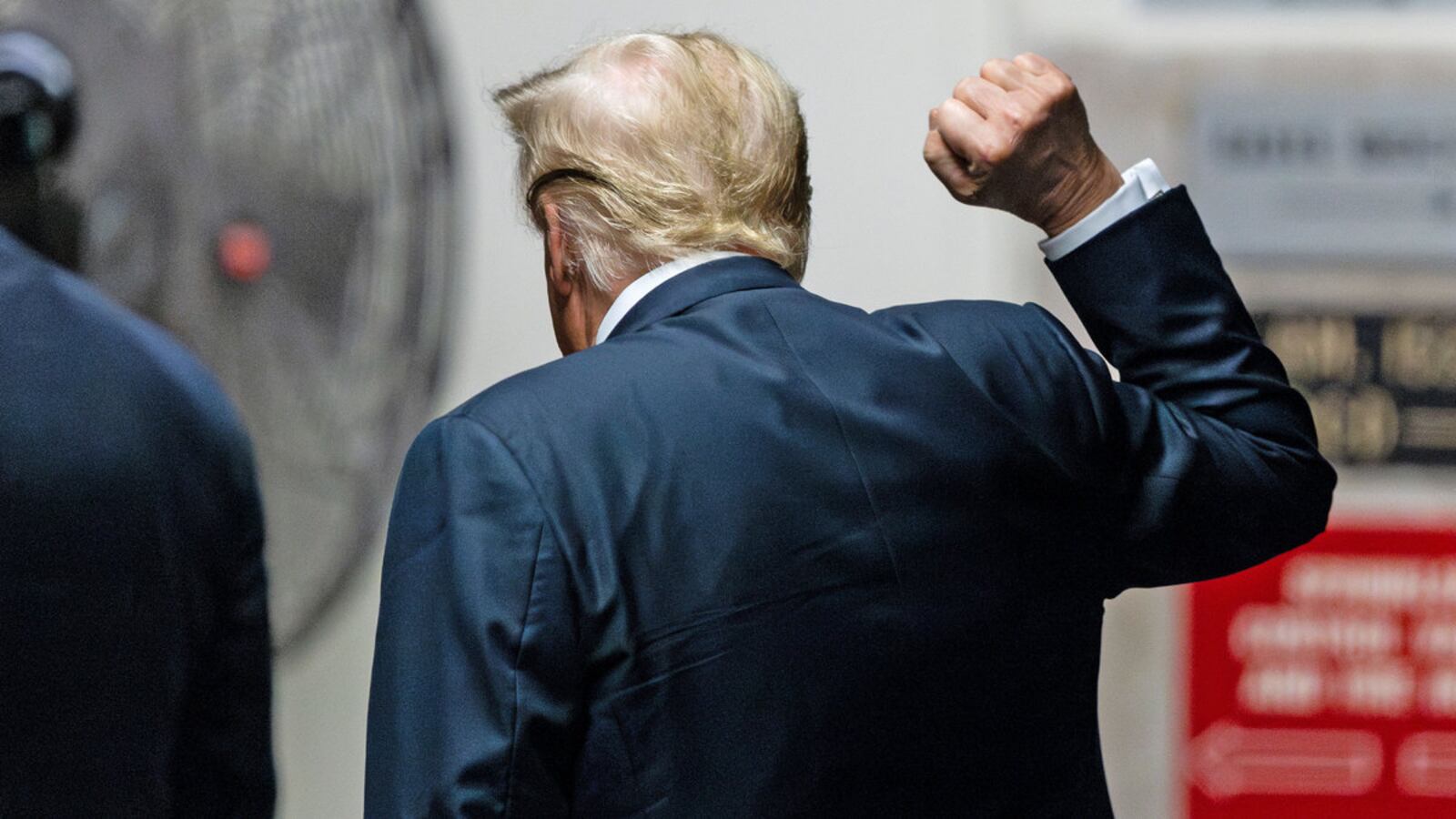

He continued: “We will fight for our Constitution. This is long from over.”

Of course, he would say that. But is this the turning point where Trump’s luck finally runs out—or merely yet another opportunity for Trump to cast himself as a victim of the “Deep State”?

The answer to this question is not merely significant in terms of Trump’s political future, but also in terms of where it leaves American justice—and where American justice itself may be headed should Trump, despite what happened on Thursday, go on to win a second term.

Thanks to Trump’s efforts, it’s fair to say his base has already been somewhat inoculated against this conviction, with three-quarters of Republicans saying (prior to the decision) that Trump was not guilty of a crime in the New York trial.

But Trump’s attempts to cast himself as a victim were not merely preemptive defensive maneuvers meant to mitigate against the downside of a possible conviction—they are also offensive weapons to attract new supporters who likewise see themselves as victims of the carceral state. During his recent speech at the Libertarian Party convention, for example, Trump joked, “If I wasn’t a Libertarian before [being indicted four times], I sure as hell am a Libertarian now.”

In a similarly troubling move, Trump hosted a rally in the Bronx, New York, last week, where he invited two controversial rappers (one of whom is facing attempted murder charges) on stage to speak.

Trump’s behavior flies in the face of the traditional “law and order”/“rule of law” brand of the Republican Party.

But could Trump’s gambit actually work in modern America?

If politics is downstream from culture, Trump’s ascension should not surprise us. From The Sopranos to Breaking Bad, Hollywood has normalized certain behaviors and softened the ground for an anti-hero like Trump.

Of course, not everyone is susceptible to this sort of appeal. Trump’s gamble—from an electoral standpoint—seems premised on trading normie suburban voters who can’t imagine voting for a convicted felon for a coalition of disaffected, anti-establishment Americans who feel increasingly victimized and left behind by institutions.

Interestingly, this is a cohort that is more diverse than the traditional GOP electorate. If you’ve seen the famous Saturday Night Live episode where Tom Hanks appears on “Black Jeopardy,” you know what I’m talking about.

The joke is that non-college white MAGA supporters and some African Americans have more in common (including a conspiratorial belief that the game is rigged against them) than they might otherwise think—a notion that Trump has (without referencing the skit) embraced.

On one hand, this is a hopeful idea. On the other hand, it’s a terrifying one.

Supporters of former U.S. President Donald Trump demonstrate following the verdict in his criminal trial over charges that he falsified business records to conceal money paid to silence porn star Stormy Daniels in 2016, in New York City, U.S. May 30, 2024.

Mike Segar/ReutersBut is swapping soccer moms and bougie suburbanites for conspiratorial or disaffected voters a winning bet?

That is the $64,000 question. Indeed, the wisdom of making this trade is at the heart of questions regarding how to model political polls—and whether Trump is really winning right now, as several polls indicate.

This question gets even more complex when you consider that this trade involves Trump swapping a coalition of voters who vote habitually (in special elections, off-year elections, etc.) for a coalition that votes less consistently.

As CNN political analyst Ron Brownstein notes, Joe Biden is “running best among Americans with the most consistent history of voting, while former President Donald Trump often displays the most strength among people who have been the least likely to vote.”

One amazing finding that Brownstein cites is that “With Black voters, Biden’s lead was just 10 points among those who did not show up for any of the past three elections, but over 80 points among those who participated in all three.”

If this reordering sticks, we could end up with two political parties that represent two different Americas: A college-educated America that still believes in institutions, and a second America that is convinced the game is rigged and that only a strongman, scofflaw, and sonofabitch—their sonofabitch—can to fix it.

Back to the trial. Trump has now been convicted, but make no mistake: This will not be electorally dispositive.

That is to say, Team Biden will still have to aggressively prosecute a political campaign just to make voters care. This is not something Biden has, heretofore, proven capable of doing.

And if Trump is elected president again in November, despite suffering a conviction, he will not have done so not just by skirting the law, but rather, by rendering it irrelevant.

What kind of presidency should we expect from a man who has consistently violated the law—and been rewarded by the voters in spite (or because) of that?

Donald Trump has learned all the wrong lessons in life, because he has never been held accountable by anybody (and we will have to wait until July to see if the sentence he is handed constitutes any real punishment). Regardless, if being convicted of a crime results in his winning the White House again, why should any law or norm stop him from doing whatever he wants to do once he gets there?