What really was on trial in the E. Jean Carroll case was our attitudes towards sexual assault.

A Manhattan jury took only three hours to find former President Donald Trump liable for the sexual abuse of the writer E. Jean Carroll that occurred almost 30 years ago, but the defense Trump mounted dated back far longer.

Trump’s defense team chose to present no evidence in the case, but relied entirely on a cross-examination of Carroll that was a showcase of sexual assault victim tropes. Trump attorney Joe Tacopina applied long-discredited assumptions about how sexual assault victims must behave if they are to be believed.

Tacopina’s strategy focused on the fact that Carroll had delayed in bringing out the allegations—and never reported them to the police—as well as the fact that she had not screamed during the attack. Both of these lines of questioning are based on ignorant assumptions about how trauma affects victims and especially sexual assault victims.

Delayed reporting by survivors needs to be viewed in light of the fact that the majority of survivors never report being assaulted. One study found that only one in five women even report the sexual abuse.

Factors that affect the decision to report include the person who committed the assault being in a position of power compared to the victim, as well as the fact that many victims blame themselves for what happened.

As a former sex crimes prosecutor, I heard many times the self-doubt experienced by victims questioning if they had somehow brought this violence upon themselves. In what I understood was due in large part to the shaming that our history has imposed upon survivors, and also what I felt was some attempt to exert control over an uncontrollable situation by thinking that there might have been something they could have done, many victims would wonder aloud to me and police if they were to blame. They wondered if they had “led the perpetrator” on and criticized themselves for not fighting back or screaming for help.

Such factors were front and center in the E. Jean Carroll versus Trump trial. Carroll testified about her feelings of shame, and one of the good friends she told about the attack advised her to not report it because Trump was so powerful that he would crush her. Which, of course, is exactly what Trump tried to do once she did go public with the accusation.

Tacopina’s focus on whether Carroll screamed during the attack ignored the well-documented research findings about how our brains react to trauma. Freezing up and dissociation are common reactions to traumatic stress, and Carroll described her feelings of being frozen during her testimony. Tacopina’s efforts to grill her about why she didn’t scream backfired on him when Carroll told him “I was in too much of a panic to scream. You can’t beat up on me for not screaming.” This caused Tacopina to retort that he was not beating up on her—which isn’t exactly the best statement for a male lawyer cross-examining a woman to make.

Thankfully, in recent years, trauma-based interviewing of sexual assault victims gradually has become the standard training and approach for sexual assault advocates and investigators. From my own experience, I have seen how such interviewing and questioning techniques are not only compassionate but far more effective in eliciting evidence in sexual assault cases. But even though the research and training have been used for many years now we are far from societal-wide understanding.

Tacopina had a duty as a lawyer to zealously represent Trump, and the fact that he used such ignorant misogynistic assumptions shows his belief that these assumptions still exist in the minds of many.

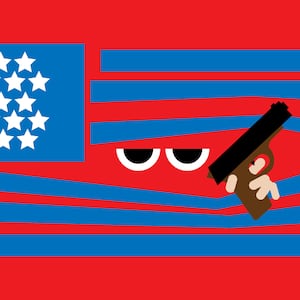

Trump’s deposition—in which he leaned into his assertion on the Access Hollywood video that his “star” status allowed him to grab women by the genitals without consent—well illustrates this. Indeed, Trump actually testified that such behavior dated back for as long as a “million years”—an obvious invocation of so-called cave-man behavior.

The jury rejected these assumptions in its verdict against Trump, but that is no sign that such attitudes have been now fully consigned to the past. Indeed, much of Trump’s appeal to his base is rooted in the idea that America needs to return to a more misogynistic and racist past in order to reclaim supposedly lost glory.

The reveal of this theme in conservative thinking has become more emboldened, not less. Let’s remember that Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion overruling Roe v. Wade relied in part on the thinking of 17th century jurist Matthew Hale, who presided over witch trials resulting in women being put to death. (Hale also believed that women could not be raped by their husbands.)

Trump and his like-minded thinkers want the progress toward enlightenment to be reversed. But courageous survivors like E. Jean Carroll and the other women who testified against Trump ensure through their courage that the progress won’t easily revert to 17th century beliefs—much less the million-year old thinking espoused by Trump.