The Justice Department’s sweeping new “superseding” indictment on Thursday of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange under the Espionage Act is a bombshell that poses grave dangers for freedom of the press. The indictment would criminalize the encouragement of leaks of newsworthy classified information, criminalize the acceptance of such information, and criminalize publication of it.

That’s criminalizing journalism.

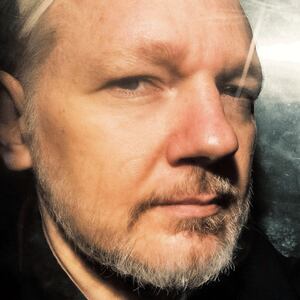

And it doesn’t matter whether you think Assange is a journalist, or whether WikiLeaks is a news organization. The theory that animates the indictment targets the very essence of journalistic activity: the gathering and dissemination of information that the government wants to keep secret. You don’t have to like Assange or endorse what he and WikiLeaks have done over the years to recognize that this indictment sets an ominous precedent and threatens basic First Amendment values. Indeed, that is undoubtedly why government prosecutors have selected this case to try to undermine crucial First Amendment principles—they are hoping the unpopularity of Assange will convince the public to look the other way.

That would be a big mistake. With only modest tweaking, the very same theory could be invoked to prosecute journalists for the very same crimes being alleged against Assange, simply for doing their jobs of scrutinizing the government and reporting the news to the American people.

The superseding indictment is vastly broader than the original indictment, which contained only one count, accusing Assange of helping Chelsea Manning hack a military computer password, and seemed deliberately crafted to minimize threats to newsgathering and press freedom. The government has added 17 new counts charging that Assange violated the Espionage Act by obtaining and disclosing classified information, and conspiring with Manning to “receive” the information, with the original computer hacking charge treated as little more than an afterthought (Count 18). The most disturbing aspect of the indictment is that it is largely premised on the claim that Assange “encouraged Manning to steal classified documents from the United States and unlawfully disclose that information to WikiLeaks.”

Nothing in the Espionage Act prohibits a person from encouraging a leak of classified or other government information. In fact, that is a paradigmatic description of what journalists do all day, every day, and that is protected by the First Amendment. As the Supreme Court declared in Citizens Union v. Federal Election Commission (2010), “Speech is an essential mechanism of democracy, for it is the means to hold officials accountable to the people… The right of citizens to inquire, to hear, to speak, and to use information to reach consensus is a precondition to enlightened self-government and a necessary means to protect it.”

The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that the First Amendment forbids the government from punishing a person who lawfully obtains information of public concern and then publishes it—even if he knows his source may have committed a crime by leaking the information. As the court explained in its most recent decision on this topic, Bartnicki v. Vopper (2001)—a case in which a labor union official and radio station disseminated the tape of a cellphone conversation they knew had been illegally recorded and disclosed in violation of federal wiretapping laws—“a stranger's illegal conduct does not suffice to remove the First Amendment shield from speech about a matter of public concern.” To conclude otherwise, the court added, would encourage “timidity and self-censorship.”

These bedrock principles are the foundation of the First Amendment. While the court has not ruled out that a compelling governmental interest of the “highest order” might justify punishing the publication of truthful information in some future case, it has never come close to greenlighting such a punishment. The Bartnicki court quoted its decision in Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co. (1979), for the proposition that “state action to punish the publication of truthful information seldom can satisfy constitutional standards.” And it relied on its famous 1971 decision in New York Times v. United States (the Pentagon Papers case), where it refused to enjoin the publication of stolen and illegally leaked classified information about the Vietnam War.

The Assange indictment contradicts all of these precedents and ignores these fundamental principles because, as a Justice Department official told reporters, “Julian Assange is no journalist.” But that’s cold comfort. This Justice Department reports to a president who has been urging the attorney general to investigate and prosecute his perceived opponents and who has been waging a war against the press, branding them “the enemy of the people,” so it is not at all a stretch to be concerned that the Assange indictment is a stalking horse for an attack on journalists.

Moreover, we can’t have the government picking and choosing who counts as a journalist and who does not. That difficult line-drawing exercise would give the government license to criminally punish journalists it does not like, based on antipathy, vague standards, and subjective judgments.

Nor does such a journalist versus non-journalist distinction comport with the law. The Supreme Court in Bartnicki expressly noted that it was applying the same First Amendment standard to the media defendants and the union official. In Citizens United and other cases, the court has prohibited “restrictions distinguishing among different speakers” because “speech restrictions based on the identity of the speaker are all too often simply a means to control content.”

Whatever law applies to Assange will likely be deemed to apply to journalists, news organizations and everyone else. And that’s why the Assange indictment should be deeply troubling to us all.