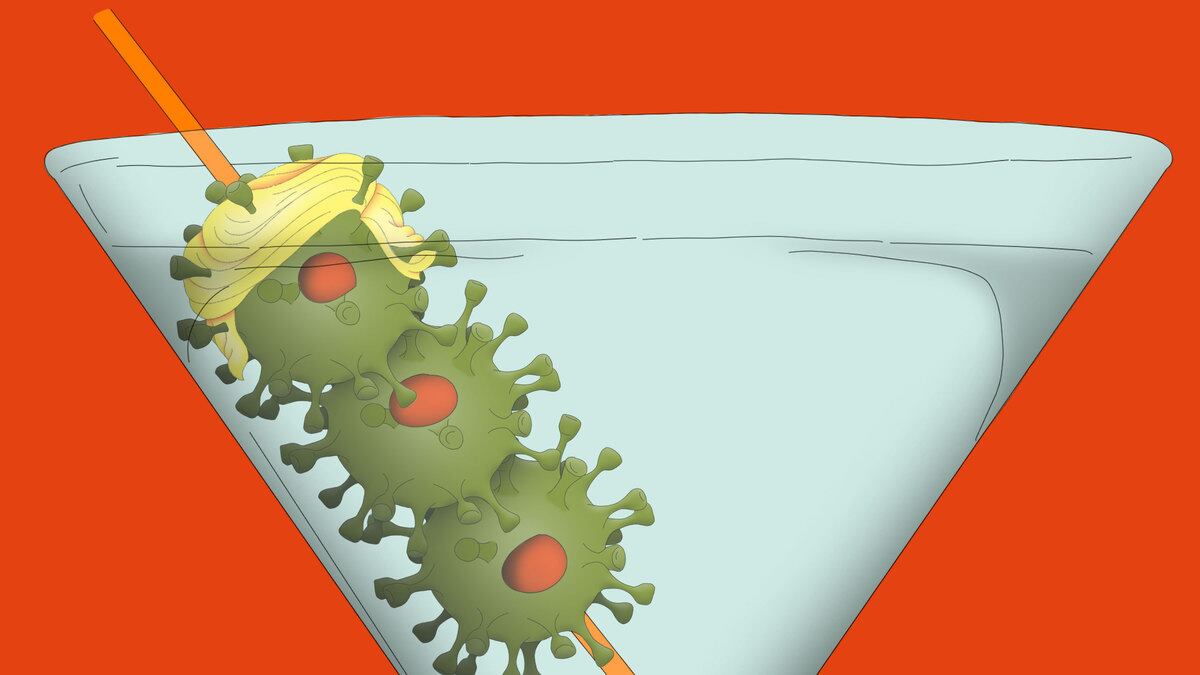

The “three-martini lunch” is back, not that it ever left. Its heyday was the 1960s, when long business lunches were part of the American dream, and the full cost of an extravagant meal could be written off. The unfairness was obvious, and it grated. Why should rich businessmen, and they were mostly men, get to dine out on steak and lobster subsidized by secretaries eating tuna fish salad and construction workers who couldn’t deduct the bologna sandwiches in their lunch buckets?

Four presidents tried to end or rein in the practice, and for the last quarter-century, the deductibility of the meal epitomized by the three-martini lunch has been cut in half, with Uncle Sam picking up just 50 percent of the tab. It is somehow fitting that under President Trump’s phony populism, and during a pandemic that has killed more than 300,000 Americans and left millions unemployed, that lawmakers saw an opening in the latest government funding legislation to restore the full 100 percent reduction for corporate lunches.

It’s framed as a way to save the restaurant industry, but it looks like once again the richest among us, who are the most likely to indulge in four-course meals to consummate business deals, will be rewarded, while the hamburger joint in the neighborhood won’t be benefiting. Some of the country’s top chefs contacted Trump directly. A resort owner, he is sympathetic, and he made sure they were heard. Restaurants have taken a huge hit. Still, there should be other ways to help owners and workers without lining the pockets of business executives.

ADVERTISEMENT

The three-martini lunch tells a story about economic unfairness, and the forces that perpetuate it. President Kennedy in 1961 drew attention to these tax breaks for business people in a message to Congress where he said that too many firms and individuals had devised ways to charge the federal government for personal living expenses, a practice he said impacted “not only our public revenue, our sense of fairness and our respect for the tax system, but our moral and business practices as well.”

Kennedy’s warning went nowhere until Jimmy Carter took a run at the issue from a populist perspective. Campaigning for the presidency in 1976, he called the U.S. tax code “a disgrace to the human race.” He railed against “rich businessmen” who write off the cost of a “$50 martini lunch” ($230 in today’s dollars) while the working class can’t deduct the sandwich in their lunch buckets and instead get stuck subsidizing the tab for phony business deductions. The average worker, Carter noted, had to pay out of his own pocket for a “rare night on the town.”

After narrowly winning the presidency, Carter sought to make good on his populist rhetoric, and in a sweeping attempt at tax reform called for business deductions to end for theater and sporting tickets, yachts, hunting lodges, country club dues and first-class plane tickets—and for only half of the infamous three-martini lunch to be deductible.

It was as though he had declared war on Washington. Time Magazine columnist Hugh Sidey called it “a country boy’s jab at the sophisticated urban’s chin.” Long luncheons with White House sources and politicians were how journalists did their job in the pre-internet era when time was not at such a premium. Ample expense accounts were the coin of the realm even for journeymen reporters.

Sidey wrote a column “In Defense of the Martini,” in which he noted, “One of the more spirited questions around Washington now is whether Jimmy Carter has ever had a three-martini lunch.” On a weekend show popular at the time, Agronsky and Company, one of the first political roundtable talk shows, Sidey opined that Carter had no understanding of how federally subsidized, alcohol-fueled meals greased the wheels of business and boosted productivity. He likened the three-martini lunch to the fertilizer that Carter, a peanut farmer, put on his crops.

William F. Buckley, the eminence grise of conservativism at the time, joined in the fun, claiming that Carter’s opposition was not to the lost government revenue but to the martini itself and that his were “code words designed to point to a lifestyle against which all the complicated glands in Jimmy Carter’s body boil in protest.”

Carter got nothing in the way of tax reform. He had prodded the sleeping giant and failed quite spectacularly. President Ford, whom Carter had defeated, said in a 1978 speech to the National Restaurant Association, “The three-martini lunch is the epitome of American efficiency. Where else can you get an earful, a bellyful, and a snootful at the same time?”

In his book, President Carter: The White House Years, Stu Eizenstat, who was Carter’s domestic policy adviser, recounts the ill-fated legislation and how Democrat Russell Long, the Louisiana senator who chaired the Senate Finance Committee, simply dismissed Carter’s earnest effort to curb business deductions. There was shared blame, Eizenstat explains, as Carter refused to kiss the ring of the powerful oil-state baron, and that was how Washington worked—or didn’t.

Carter’s populist approach failed to sway Washington’s power brokers, but it was key to his political rise. When he ran for governor of Georgia in 1970, his opponent in the Democratic primary was Carl Sanders, a wealthy lawyer and banker who belonged to the exclusive (and whites only) Piedmont Driving Club. Sanders was seen as the liberal in the race and was winning the Black vote. After a newspaper story reported on a meeting Sanders held at the club, Jerry Rafshoon, Carter’s longtime media person, filmed a television spot that opened with the door of a country club that said, “Members Only.”

“I didn’t say it was the Jewish Country Club I belonged to,” Rafshoon says, laughing as he recounts the story for the Daily Beast. The narrator said this is where “the big money boys” go to drink, and play cards, “and raise money for their candidate for governor, Carl Sanders.” Hands were shown holding glasses, dealing cards, and the closing image was a man’s wrist with expensive cufflinks, which Sanders was known to favor.

Rafshoon recites the words these many years later: “You and I were not invited. We’re too busy working for a living. That’s why Jimmy Carter is our kind of governor.”

It was a brutal ad for the time, and Carter got some pushback. He assured a woman who complained that he would have Rafshoon take it down the next time he saw him. He wouldn’t see him of course until election night, when Carter won. Populism had hit its mark.

It wasn’t until Ronald Reagan became president and oversaw a comprehensive overhaul of the tax system that the three-martini lunch got trimmed to an 80 percent deduction. Steve Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, was working on Capitol Hill at the time for the Joint Committee on Taxation. “There was a populist sentiment: Why should these rich executives shift to Uncle Sam a share of the restaurant tab? The rest of us can’t do that.” The committee’s explanation of the 1987 reform laid out in some detail how the people who benefit tend to have higher incomes, that the deductions are for lavish meals often only “loosely connected” to the business at hand, and that this disparity is “highly visible” and is one of the significant drivers of “disrespect for and dissatisfaction with the tax system.”

Reagan’s tax reform was designed to eliminate deductions, broaden the base of people paying taxes, and lower the tax rates. It passed with big bipartisan majorities. Still, an 80 percent write-off was still pretty hefty, and it wasn’t until President Clinton’s Budget Act in 1993 that it was shaved to 50 percent. And there it remained until the stroke of Trump’s pen restored the infamous deduction back to 100 percent. “Restaurants are decimated. That was the driver, to find ways to help the restaurant industry,” says Rosenthal. “I understand the objective, but people can’t have three-martini lunches at their neighborhood hamburger joint. I’m not sure it’s effective. The best thing you can say about it is that it expires at the end of 2022.”

Until then, it will go down as part of Trump’s legacy because it’s a favor for the rich he went out of his way to do. We may have 330,000 dead, but at least rich people will be able to write off $230 lunches.