Can’t get enough of The Beast’s biting political opinion? Join Beast Inside to support The Beast and get first access to top stories.

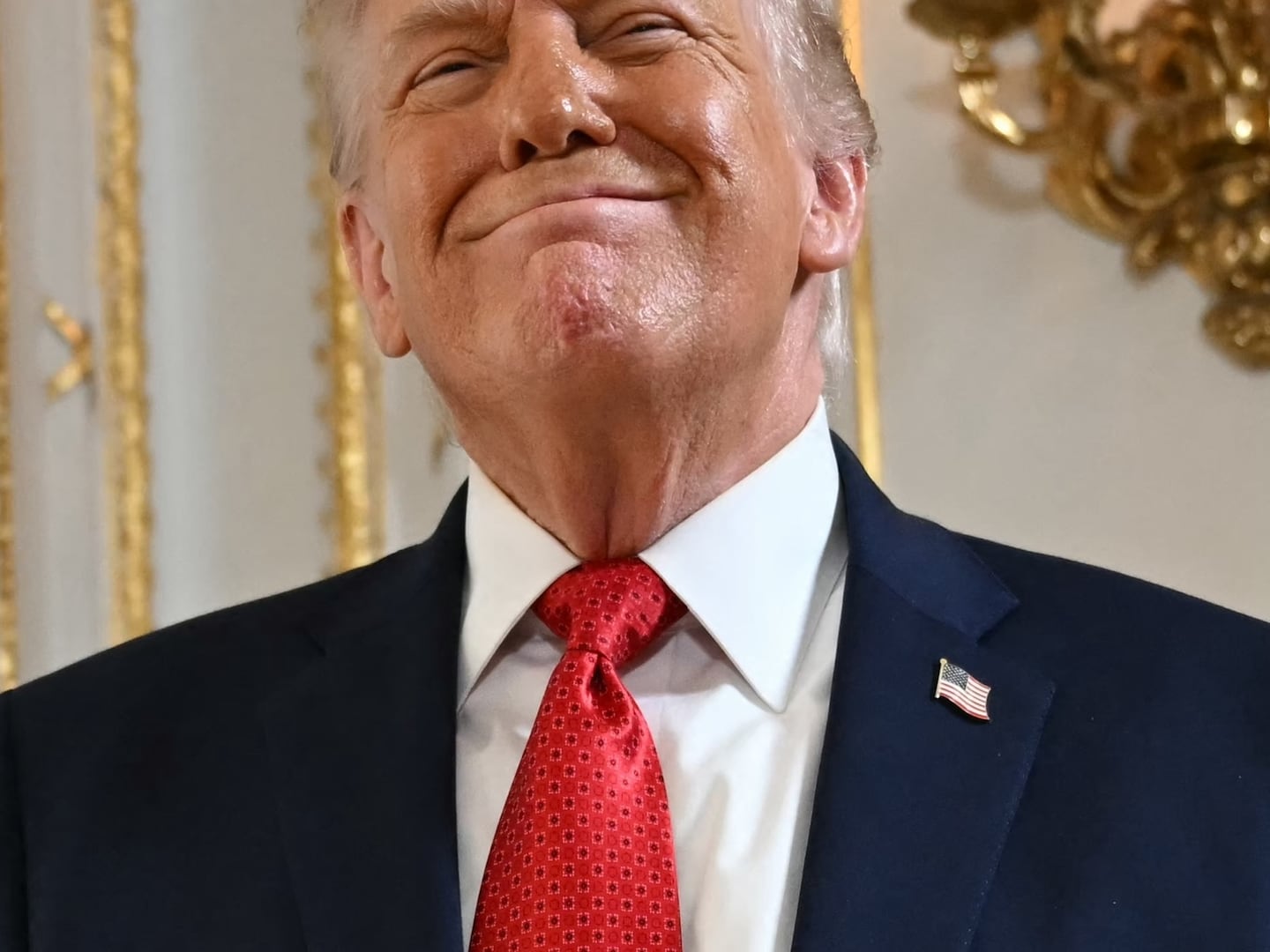

PARIS—Donald Trump's most vital Mideast allies are trending fast toward tyranny, but does an American president who's always shown a rather conspicuous penchant for dictator-envy really care?

If not, he should. We all should. Because two of the most stable governmental systems in the highly unstable Middle East, Saudi Arabia's monarchy and Israel's democracy, are threatened by leaders who, it appears, will do just about anything to hold on to power.

In Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, only 34 years old and already the de facto ruler of the country where his enfeebled octogenarian father is king, reportedly has arrested an uncle and at least three cousins, one of them a former crown prince. This amid completely unconfirmed but politically volatile rumors they were plotting a coup against MBS, as he’s known, or that his father, King Salman, has died and he is moving quickly to consolidate his absolute power. Given MBS’s record in connection with the literal butchering of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, nobody puts anything past him.

In Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is claiming his election was stolen by conspiratorial opponents in league with Arab “terrorists,” and wants “the people” to set things straight, essentially calling them to the streets to keep him in power.

Since November, at least, some of Netanyahu's opponents have suggested he might opt for civil war before he'd give up his grip; others have said that is inconceivable, but in Netanyahu's case his conspicuous lack of scruples makes all sorts of accusations seem plausible. He has been blocked from forming a government after last week's elections not only because his coalition fell three Knesset seats short of a majority, but because he has been indicted on multiple charges of corruption and his trial is set to begin on March 17.

"We have lost all shame and decency," retired Israeli Supreme Court Justice Elyakim Rubinstein told the Center for Jewish and Democratic Law at Bar Ilan University on Wednesday in a warning about the threat to democracy unprecedented in Israeli history. "Conspiracies are floated from every platform. Plot lines such as 'the police and public prosecutors are joining forces to oust the prime minister'—it is completely false. These are things that never happened."

Rubinstein decried what he called "a sort of brainwashing indicating that everything is terrible and rotten" when that is not the case at all.

By Saturday, after convening an "emergency meeting" Netanyahu vowed "the public will yet settle the score with those trying to oust me."

The response to histrionics by Netanyahu and his partisans by the former armed forces chief of staff, Benny Gantz, who most likely will form the next government, was measured but firm. "Netanyahu and his people are intentionally fueling violent and extreme discourse," Gantz said in a Facebook post on Friday. "Netanyahu is ignoring the election results and is prepared to burn everything on his way to avoiding trial."

While Americans may find it easy (maybe all too easy) to understand the kind of threat to democracy that is taking shape in Israel, the situation in Saudi Arabia, although more sui generis, is no less important.

Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman attends a working breakfast with U.S. President Donald Trump during the G20 Summit in Osaka on June 29, 2019.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty ImagesThe Kingdom, as it is called, was founded in the 1920s and '30s by a desert warrior named Abdelaziz ibn Saud. After oil was discovered in the country that he named for his family, the promise of enormous riches loomed on the horizon, and in the waning days of World War II, on a ship called the Quincy on the Great Bitter Lake that is part of the Suez Canal, Abdelaziz and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt reached an agreement to assure the Saudi monarchy's security while benefiting from its oil.

Abdelaziz had more than 50 sons with multiple wives and concubines, and all of them were potential successors. After his death in 1953, the crown passed from one brother to another decade after decade in an increasingly sclerotic gerontocracy.

There were power plays, to be sure. King Faisal ousted his dissolute predecessor, suppressed the most crazed of the religious fanatics who had supported the monarchy beforehand, and was murdered by a relative of one of those killed.

But by and large the system worked as senior princes reached consensus on who should be the next in line and the succession was orderly.

Eventually, a powerful clique of princes emerged who were full brothers: sons of Abdelaziz and of the same mother, Hassa bint Ahmed al Sudairi. There were seven of them and they were known to Saudi watchers, inevitably, as "the Sudairi seven."

The arrests and intrigues we are seeing now are within that powerful subset of the House of Saud.

King Fahd bin Abdelaziz was a Sudairi. When he died in 2005, he was succeeded by Abdullah bin Abdelaziz, who was not a Sudairi, and was his mother's only child. There was an understanding that the Sudairis would return to power when Abdullah died. But that took longer than expected. And while Abdullah lingered on the throne, the senior Sudairi successors—Defense Minister Sultan and Interior Minister Nayef—died of natural causes. That left Salman bin Abdelaziz as the crown prince and, when Abdullah finally shuffled off the mortal coil in 2015, the king.

What nobody had reckoned on were the ambitions and charisma of one of Salman's younger sons by one of his later wives. Mohammed bin Salman was only 29 when his father became king, but very soon was in charge of just about everything, including the military and the economy.

In the five years since, he has defanged the long-feared religious police, opened up Saudi Arabia to mass entertainment, and given women, at last, permission to drive. But he has imprisoned, intimidated and extorted anyone rich enough to challenge him.

MBS also went to war in Yemen to prove he was tough on Iran, wading into a quagmire from which Saudi Arabia has yet to extricate itself. But, most importantly for Americans, he carried out the financial seduction of Trump son-in-law and adviser Jared Kushner, then Trump himself. All that Saudi money was irresistible to such artists of the deal, and Riyadh was the first foreign capital President Trump visited. You may remember Trump dancing with a sword and putting his hands on a weird glowing orb.

The Khashoggi murder in October 2018 crystallized the fears of many of MBS's fellow princes that he was as dangerous as he was charismatic, but by then only the bravest of his critics would speak out, and they knew what the price could be: imprisonment, torture, or worse.

So who could challenge him? Who would? The question here is not who did, but who might conceivably have done so.

High on the list was MBS's uncle, Ahmed bin Abdelaziz, at 77 the youngest of the Sudairi sons and thus in the traditional system dating back to 1953, the king-in-waiting—even though he seemed to have been passed over.

More problematic still for MBS was a member of the second generation, the son of Nayef, another Sudairi, Mohammed bin Nayef known as MBN. As the head of Saudi Arabia's counterterror ops and then as interior minister, MBN was well known and well respected by the U.S. government, including and especially the CIA.

Indeed, MBN actually held the position of crown prince and heir apparent in the early days of King Salman's rule until MBS, using some of the same team of thugs that went on to murder Khashoggi, forced him to resign.

Both of the senior princes MBS would see as a threat, his uncle Ahmed bin Abdelaziz and his cousin MBN, had kept low profiles of late, and MBN was said to be under house arrest since his ouster as crown prince.

Now, according to the Wall Street Journal's reporting on the arrests, they could face prolonged prison terms or, indeed, execution.

Bibi and MBS. Such are the pillars on which Donald Trump has built policy in the Middle East.

Noga Tarnopolsky contributed reporting from Jerusalem.