The team of lawyers assembled by special counsel Ken Starr to investigate President Clinton’s relationship with Monica Lewinsky was made up of aggressive, hard-charging types—smart on the law, ideologically conservative, and morally and religiously offended by Clinton’s behavior.

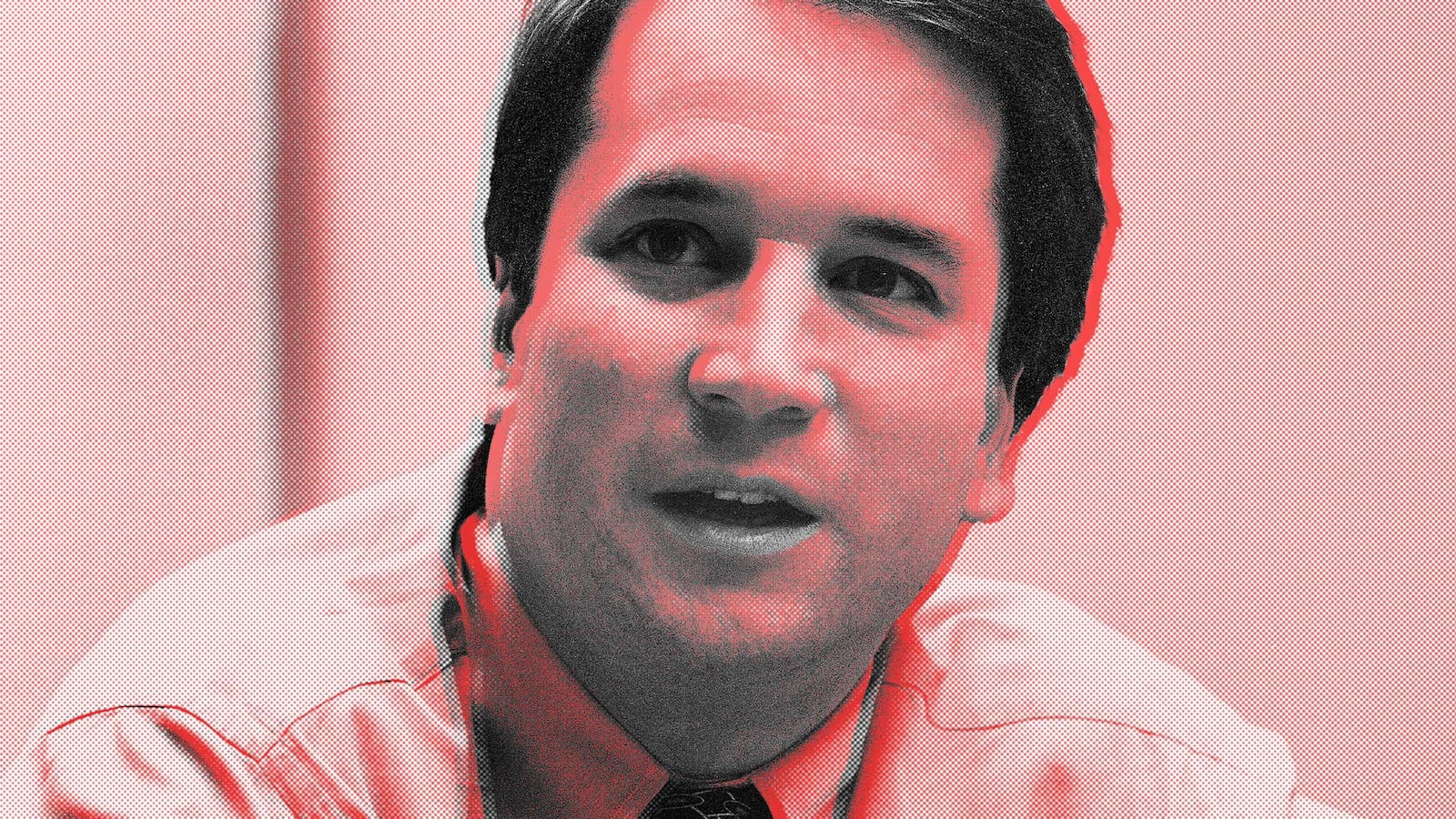

One of those lawyers, Brett Kavanaugh, is now President Trump’s nominee for the Supreme Court, to fill what had been Justice Anthony Kennedy’s key swing seat. Republicans see him as another home run, cementing a conservative majority on the Court. Democrats see him as a political operative in judge’s robes.

The Clinton team assumed he was among those regularly backgrounding the press on President Clinton’s relationship with Monica Lewinsky. One reporter who covered the investigation describes the then 30-something Kavanaugh as “very cautious and careful, and not the kind who was likely to leak anything of substance.”

Kavanaugh worked the Vince Foster case, and after a long and costly investigation wrote a 300-page memo debunking conspiracy theories suggesting that Foster, a White House lawyer and longtime Arkansas friend of the Clintons, had been murdered and files taken from his office.

When Hillary Clinton’s missing billing records from her time at the Rose Law Firm showed up almost two years later elsewhere in the White House, Kavanaugh was the lead prosecutor grilling the Clinton team when the first lady appeared before the grand jury in January 1996. His performance was professional and straightforward, recalls a member of Clinton’s legal team.

Expanding on that assessment, and on other professional interactions in Washington, this source says of Kavanaugh, “He’s very congenial, not a flame thrower, but a very hardline conservative, more like [Chief Justice] John Roberts. The two of them are similar. They keep their heads down, they’re very right wing in a very inside Washington way.”

When President Clinton testified before the grand jury in 1998, “There were 7 people, including Starr, and he [Kavanaugh] was not one of them, I’m not sure why,” says this source. “I was never sure what the hierarchy was, it was like facing a wall with lances pointing out.”

Kavanaugh wrote the portion of the Starr report that lays out the grounds for impeachment based on President Clinton’s alleged abuse of executive privilege, but says he did not draft the narrative section, which contains the intimate details that made the Starr report X-rated.

“Chronologically, Clinton had admitted to the affair,” says Nan Aron, founder and president of Alliance for Justice. “This was just the pile-on of lurid details.” It backfired for Starr, says a member of the Clinton team. “The president admitted to wrongdoing, he didn’t go into detail, but everybody knew what it was. They didn’t need to write that pornographic report. Without that, they would have had a much stronger referral [for impeachment].”

Then Clinton lawyer Lanny Davis, who’s now representing Michael Cohen, responded in an e-mail about Kavanaugh: “Never met him. If lying about sex was an impeachable offense am looking forward to his hypocrisy re Trump’s serial lies.”

In his book Uncovering Clinton, then Newsweek reporter Michael Isikoff writes that Kavanaugh believed it was an impeachable offense for Clinton to invoke executive privilege to conceal his personal misconduct. But the tawdriness of the case bothered Kavanaugh.

“Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night and wonder to myself, ‘what am I doing?’” Isikoff quotes him saying. “There are a lot of mixed emotions about this.”

When Kavanaugh learned on the morning of Sept. 11, 1998, that Congress was about to release the report and put it on the internet, according to Isikoff, he quickly composed a letter to Speaker Newt Gingrich asking him to hold off because of the report’s “highly explicit” material that is “almost certainly inappropriate for wide public dissemination.” Starr intervened, and the letter—which was probably too late in any event—was reportedly never sent.

According to a report compiled by the Alliance for Justice when Kavanaugh was first nominated by President Bush for the D.C. Circuit in 2003, Kavanaugh had been assigned to attack the Clinton administration’s claims of executive privilege. He successfully challenged Clinton’s claim of attorney-client privilege to block a subpoena to Bruce Lindsey, a longtime associate and White House attorney. Kavanaugh successfully challenged Clinton’s attempt to withhold attorney notes, and he rebutted a “protective function” claim that allowed Starr to bring Secret Service agents before the Grand Jury.

The only executive privilege claim Kavanaugh did not overturn came from Vincent Foster’s attorney after Foster’s death. The court honored the privilege even though Foster was dead.

Kavanaugh’s discomfort with the Starr report was limited to its immediate release, not to the details included, which he and others deemed necessary to prove their case against Clinton. After the probe was over, he joined with other Starr attorneys in a Washington Post op-ed calling him “an American hero” who “uncovered a massive effort by the president to lie under oath and obstruct justice.” The op-ed concluded:

“Over time, fair-minded people will come to hail Starr’s enormous contributions to the country and see the presidentially approved smear campaign against him for what it was: a disgraceful effort to undermine the rule of law, an episode that will forever stand, together with the underlying legal and moral transgressions to which it was connected, as a dark chapter in American presidential history.”

Later, Kavanaugh was among the band of lawyers who headed to Florida to insure George W. Bush won the 2000 election recount. He was rewarded with a job in the Bush White House where he worked diligently to uphold President Bush’s claims of executive privilege, and had a major hand in selecting Bush’s judicial appointments.

Before that, he had been a partner at Kirkland & Ellis, where he represented pro bono the Miami relatives of Elian Gonzalez, the Cuban boy rescued at sea. It may not take much imagination to draw a clear line from his personal activism to the rulings he would likely make if seated on the Supreme Court.