It was thought that there was only one wild jaguar left in the U.S.

But a second “big cat” was spotted recently in Southern Arizona and now experts are working to learn more about it.

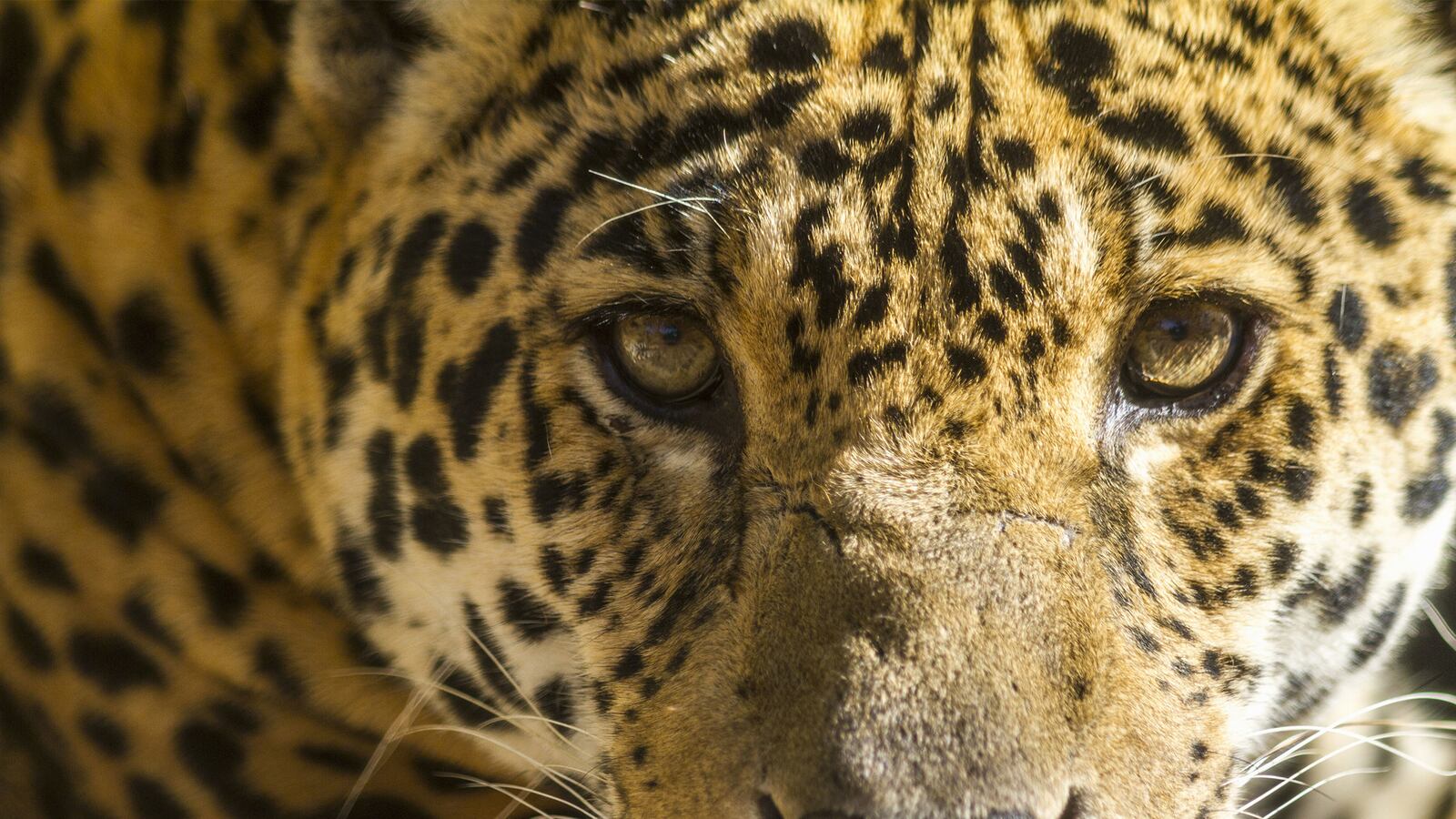

The North American jaguar is on the brink of extinction in the U.S. The jaguar is the only “big cat” native to the Americas. (Globally, big cats or the genus panthera include lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars.)

This symbol of America’s rugged West represents the wild beauty of our country—a beauty that is literally about to cease to exist if we do not do something about it. There are two cats still roaming the U.S. It is believed that both are males.

The only known female jaguars in proximity to the U.S. remain in Mexico.

Historically the jaguar inhabited the Americas from Argentina, north to Central America and Mexico, and into the U.S. states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

Jaguars need vast amounts of land, including mountainous corridors, to travel, mate, and reproduce. As human population densities increased in the Southwest, the growth of highways and fences limited the jaguars’ abilities to roam and procreate and the jaguar population greatly diminished. According to recent records, the last known female jaguar in the U.S. was shot in 1963. This fact puts obvious limits on the species as a whole.

The current walls and fences along America’s southern border—and the proposal by Donald Trump to expand these—will continue to limit the jaguars’ reproductive capabilities as well as their access to wilderness corridors between the U.S. and Mexico.

As I sit here, in my office in Nogales, Arizona, I literally look at the border wall and I can see Border Patrol towers and lights that glare into people’s homes at night, 12 lines of traffic, stopped up for hours at times.

Yet on the horizon are the beautiful pine-covered mountains and grassy hills, with the most superb sunsets in the world.

I remember how it once was—without the looming wall—when families crossed to have lunch with their abuelos, or grandparents, and returned to the office for the afternoon’s work.

Now, with the wall, people spends hours in line, trucks wait up to 20 hours to cross produce, and jaguars, well, they just don’t get to mate anymore.

Until recently, America’s only wild big cat was a jaguar called, “El Jefe,” or “The Boss”—a nickname given to him by schoolchildren in Tucson, Arizona. He was tracked recently by the Center for Biological Diversity. Now, it seems we have a second jaguar, who was photographed on Dec. 1 on the Ft. Huachuca Trail, in southeast Arizona.

“Preliminary indications are that the cat is a male jaguar and, potentially, an individual not previously seen in Arizona,” Dr. Benjamin Tuggle, regional director for the Southwest Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said in a report to Arizona Central.

Another jaguar, Macho B, was accidentally and mysteriously killed in 2010 by a Game & Fish employee.

Sightings of El Jefe have occurred in a corridor near Nogales, Arizona, and Sonora, in the Santa Rita Mountains. The border region to the south has seen construction of border walls and boundaries that limit wildlife crossing, and more specifically, to the jaguars’ ability to mate.

We really do need to import a wife for El Jefe.

We can reintroduce female jaguars from Northern Mexico into the United States. In fact, The Northern Jaguar Project (a U.S. nonprofit, affiliated with a Mexican nonprofit) focuses efforts on creating a stable jaguar population in Northern Mexico to eventually see the return of the jaguar to the Southwest U.S.

Jaguars in northern Mexico need to be protected so that the jaguar population can re-enter Arizona and be re-established in the U.S. And travel corridors need to be protected so that El Jefe, and future jaguars, can move, reproduce, and and flourish again.

Advocates want to designate more than 50 million acres of critical jaguar habitat in the Southwest and to protect this species from government traps, snares, and poisons.

The Center for Biological Diversity also opposes walling off the U.S.-Mexico border to ensure that jaguars will always have access to the full extent of their range.

The recent sightings offer a glimmer of hope for the return of the majestic North American large cat. For now, at least, the border landscape still provides wilderness and an opportunity for female jaguars residing in northern Mexico to encounter the males in Arizona. This is exciting, at least to large cat aficionados like me. The border region is also my home—it includes the spectacular Sonoran desert, with 60 mammal species, 350 bird species, 20 amphibian species, over 100 reptile species, 30 native fish species, and more than 2,000 native plant species.

I ask myself, if this were happening on another continent, let’s say Africa, and the lion were about to become extinct, would Americans be outraged? Surely we would send donations and we would protest. People cared about Cecil the lion who was killed in Zimbabwe, so why not about El Jefe and the latest spotted jaguar?

We are all interconnected and Trump’s wall not only hurts people and economies but also wildlife and our last remaining wild jaguars.

El Jefe and the newly discovered jaguar are symbols of the importance of biodiversity. Greater species diversity ensures natural sustainability for all life forms, ours and theirs, together.

A species may be doomed in our futile attempt to wall out people. With Trump’s wall, we risk so much more—positive ties with Mexico and Latin America, positive economic growth, and the loss of our most beautiful large cat, the jaguar.

Gail Emrick is the Executive Director of the Southeast Arizona Area Health Education Center, a health workforce development agency based in Nogales, Arizona, serving three counties on the U.S.-Mexico border. Her office window literally looks out at the border wall and beyond. She is an Arizona native, and a Tucson Public Voices Fellow with The OpEd Project.