There’s a small but growing chance that competition could ultimately save American government from the clutches of our badly broken political system.

A growing number of very bright, civic -minded folks are putting their shoulders behind the wheel to achieve that goal. They’re working to leverage the same Internet-powered forces that let new competitors enter and dominate dozens of major industries over the past twenty years. In the process, they may be creating a moment for new political competition unlike anything Americans have seen since the Republican Party’s first national election in 1856.

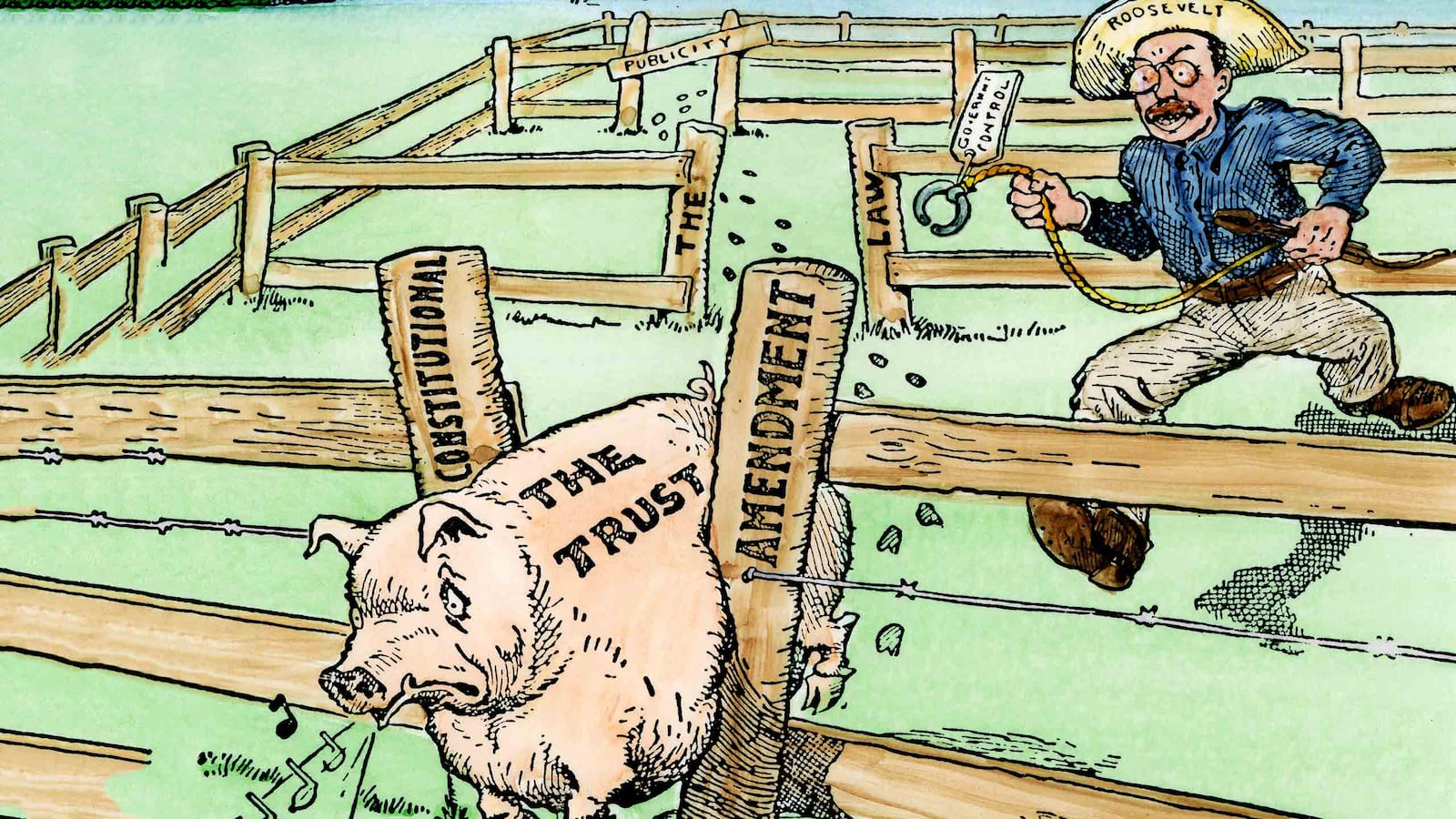

Why has this moment taken so long to arrive? Mostly because the GOP and Democrats have become political versions of the giant interlocked 19th century business trusts formed by collusive “competitors” whose real purpose was to wring monopoly profits out of American consumers of oil, steel, meat, whiskey, rail transportation, and just about every other major industry in the nation at the time.

How? By keeping competition out. The trusts used predatory pricing power, kickbacks, dirty tricks, and outright bribery and corruption to prevent new companies from competing with them. That persisted until the American public got wise to how much better life would be with competition. Republican Senator John Sherman of Ohio launched the trustbusting-era with the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in 1890, followed by President William McKinley forming the U.S. Industrial Commission to actively investigate and regulate the trusts.

But the trusts didn’t go down quickly, and they didn’t go down without a vicious fight. The biggest buster of all was President Theodore Roosevelt. He plunked the issue squarely at the forefront of his administration and kept it there – and the idea of anti-competitive collusion in business became clearly and patently unacceptable in the United States.

It took almost 20 years of enforcement activities for that to happen – and that only after years of abusive behavior by the trusts.

The two major parties have enacted almost two centuries worth of self-protecting election laws and regulatory formats. They have, effectively, made their two-party trust legal, and erected what economists would call barriers to entry for any possible competitor. They have gerrymandered, by some estimates, more than 90% of House congressional districts into non-competitive safe seats, and they have created ballot-access hurdles that make it extremely difficult for prospective independent presidential candidates to have a realistic hope of competing in 50 states.

In business, no competition means horrible service and high prices. (Cable TV, anyone?). In politics, no competition means horrible nominating processes, horrible candidates, and horrible campaigns. It also means, these days, that “party trust” politicians feel no need or desire to actually govern effectively, so long as they’re playing hard to their base. They can, and have, remained obstinate, obstructionist, and extraordinarily strident without the slightest worry of creating new political competitors.

Conventional wisdom has been that those barriers to entry have rendered the two parties as the permanent rulers of the American political system. But that’s what Yellow Cab and Sears and the newspaper industry used to think about their businesses, too.

The current wave of competitive political movements could be traced back to Unity ’08 – a nascent effort I was recruited into in 2006 by my friend, the late, great Hamilton Jordan. Its founders saw what they believed was a false polarization fueled by radically-minded wings of both parties, and sought to create an Internet-powered independent unity candidacy in the 2008 presidential election. That effort went nowhere, more or less – but 11 years ago, social media was in its absolute infancy and the news media was still dominated by fantastically profitable and powerful giants. And 11 years is a long, long time in this new information age.

“There’s a lot going on in a lot of places,” Jim Jonas told me. Jonas is a pedigreed former Republican communications strategist (he started his career working for Roger Ailes, then Lamar Alexander) who’s emerged as a Yoda-esque wise man of the competitive political movement. “There hasn’t been a lot of coordination between these groups in the past and there hasn’t been a lot of money, either, but that’s changing,” Jonas said. He convened gatherings of about two dozen competitive movement leaders last summer in Denver and again earlier this spring in Kansas City, and said more are on the way.

Here’s a quick three-bucket shorthand way to classify these competitive political efforts:

- Independent candidates – Few and far between, but now apparently growing in number. Senator Angus King of Maine governed his state as an independent and was elected to the U.S. Senate as one, too – though he caucuses with Democrats. His fellow Downeaster, Maine State Treasurer Terry Hayes, has filed to run for governor as an independent next year. And Kansas’s Greg Orman, nearly won a U.S. Senate seat as an independent in 2014 and has been mentioned as a candidate for governor in 2018 too. This new wave of independents is specifically eschewing party nominations, believing the parties themselves are broken.

- Political organizations – Groups like The Centrist Project, the Serve America Movement and the Independent Voter Network are creating focused elements or activities (candidate recruitment, fundraising coordination, media content and curation) that look an awful lot like components of a nascent movement or party.

- Election reform initiatives – Groups focusing on election law and regulatory reforms to weaken the iron grip of the two parties on nominating processes and elections themselves. Healthcare CEO Kent Thiry put up more than $1 million last year to help fund Let Colorado Vote, which sponsored a successful ballot initiative to create an open presidential primary, while no less than Nirvana’s Krist Novoselic chairs the board of FairVote.org, which pushes for similar voting changes around the country.

Within these three tributaries there are common elements needed to disrupt the American political system: money, organization, policy, and candidates.

Great candidates don’t want to bear the slings and arrows of a campaign unless they believe they can win. Part of what would help them win would be great ideas and a great agenda. But in our wildly complex and revolutionary times, those kinds of sophisticated policy proposals can largely only come from experienced hands willing to depart from their traditional party homes. And very few of those policy experts, depending on those partisan relationships to stay relevant and feed their families, have been willing to join the rebel cause.

Meanwhile, building a party organization takes volunteer effort, which generally comes from followers, who generally need to be inspired by a prospective leader. And truly inspirational independent candidates have been few and far between.

But a national government in free fall may now be inspiring a change in prospective candidate sentiment.

“I believe there are compelling candidates who will be willing to run as independents,” says Greg Orman, who led longtime GOP Kansas Senator Pat Roberts in 2014 polls until a late and massive advertising blitz by outside interest groups pulled him down. “But those candidates will need infrastructure and support systems that have been slow in developing.”

Orman cited the efforts of the Centrist Project as a path to traction. “They’re actually building a toolkit for independent candidate success and they’re talking to prospective candidates to show them what they’ve got and why they think they can win. If they can start to mimic the resources available to major party candidates, independents will take a huge step forward.”

The Centrist Project’s Executive Director Nick Troiano – now teamed with Evan McMullin’s 2016 presidential campaign director Joel Searby – is working within his still-constrained resources to shower a few sparks on the dry political forest floor. They believe their “fulcrum strategy” – electing a small band of independents that would hold the balance of power in a given state legislature – is the path forward.

“The largest barrier we face to getting traction is not structural or organizational – it’s psychological,” Troiano says. Independent candidates “need to put some wins on the board – so we’re focusing down-ballot in places that we think the fulcrum strategy can work in the state house.”

They’re planning to test that thesis in 2018 in Colorado, where Troiano has now physically moved as a kind of all-in bet. “There’s no silver bullet, no top-down way to make this happen. But over the next five to seven years, we think we could affect the balance of power in ten states. And then look out.”

Troiano recruited Searby to join him as the Centrist Project’s chief strategist. Searby is focusing on candidate recruitment for upcoming cycles. “I’m trying to be realistic and sobering (about) what running takes and what personal sacrifices it brings,” he says, noting that individuals with existing professional stature or a significant network of their own make the most effective independent candidates, in addition to those who can self-fund their campaigns.

“Most of all though,” Searby says, “the question is: Are they someone of character and integrity and do they have an ability to lead? If you get that right, the other pieces can follow.”

The Centrist Project convened a meeting of declared and potential independent candidates for the U.S. Senate in Philadelphia earlier this month, as well as activists and supporters dedicated to the competitive political movement. Said Searby in a statement, “The hope and determination in the room was kinetic.”

Finally, little of scale can or will happen without money. “There hasn’t been a lot of traction with funders - yet,” says Jonas. “Everybody understands the problem at this point, but this fight is going to be a ten-year multi-faceted slog through the marsh…Entrepreneurs often don’t want to play in that time frame – they want to know the one thing they can do that’s disruptive. But a breakthrough will require more than one thing.”

No Labels co-founder Bill Galston still thinks there’s hope for the two-party system. “We spend a lot of time thinking about that,” said Galston of the notion that the system is irreparably broken. “There’s a perennial temptation to say the two-party system is defunct or brain dead, but creating a new national party is a very tough row to hoe. Independent movements are more like insects that sting and die – they have an effect on the body, but they themselves don’t survive.”

But for those more disruptively-minded than Galston, if the forest-fire analogy is the right one, President Donald Trump has proven to be a giant can of accelerant. The personal revulsion that he spurs in a significant portion of the voting population, as well the self-inflicted wounds that have pounded his approval numbers lower and lower, send many Americans in search of a systemic antidote.

And vitriolic leadership from Democrats like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, the erratic Rep. Maxine Waters, and quasi-socialists like Senator Bernie Sanders is doing much the same thing in the other direction.

A further tipping point could come if a portion of his Trump’s core supporters become disillusioned with him – either for his alleged Russian dalliances, his personal conduct or his legislative failures. Would those voters turn back to traditional Republican politicians, or would they gravitate toward a more aggressive, completely “outside-the-swamp” box?

Trump’s 2016 victory has had the effect of making successful non-politicians believe that important elections really can be won by outsiders to the system. And they’re right. The Internet-fueled death spiral of the traditional news media, the rise of social media platforms as a high-accessibility means of communication, and the extreme targeting capabilities of digital advertising platforms all play a role in enabling insurgent movements, whether those are in politics, business or popular culture.

While 20th century Americans have watched (and participated in) the downfall of multiple industrial giants at the hands of Internet-enabled competitors, many Washington observers (particularly those inside the Beltway) argue that politics is different. Too many of those barriers to entry, they argue, and too many benefits that have accrued to the two incumbent parties for them to be displaced by new entrants.

But of course, that’s what the about-to-be-disrupted always say – such as when, just a decade ago, Rupert Murdoch argued that the Internet wouldn’t kill off newspapers, or when Disney CEO Robert Iger said that ESPN’s unbundling-related subscriber disaster was just a short-term problem. But as the saying goes and science confirms, “You never hear the bullet that kills you.”

By observation, organizations that are purpose-built for one technological or societal era rarely seem to survive the transition into the next – particularly when new organizations, specifically built for the new era, show up to compete. There’s a reason capitalist economies have virtually no 200 year-old companies.

“The opportunity for a third party or some other kind of third way is enormous,” said Republican campaign strategist, full-throated Never Trumper and Daily Beast contributor Rick Wilson. “The Republican brand has been busted for good by Trump.”

He doesn’t have much kinder words for the Democrats, either. “As long as they lean toward the hyper-progressive Bernie model,” he said, “they’re going nowhere.”

“The political iceberg hasn’t sheared off yet,” Wilson continued, “but the two parties we’ve got are broke-ass, tech-ignorant dinosaurs with crust in their code that are simply not suited to the modern era. Something built a new way has the potential for enormous growth.”

Let’s hope so.