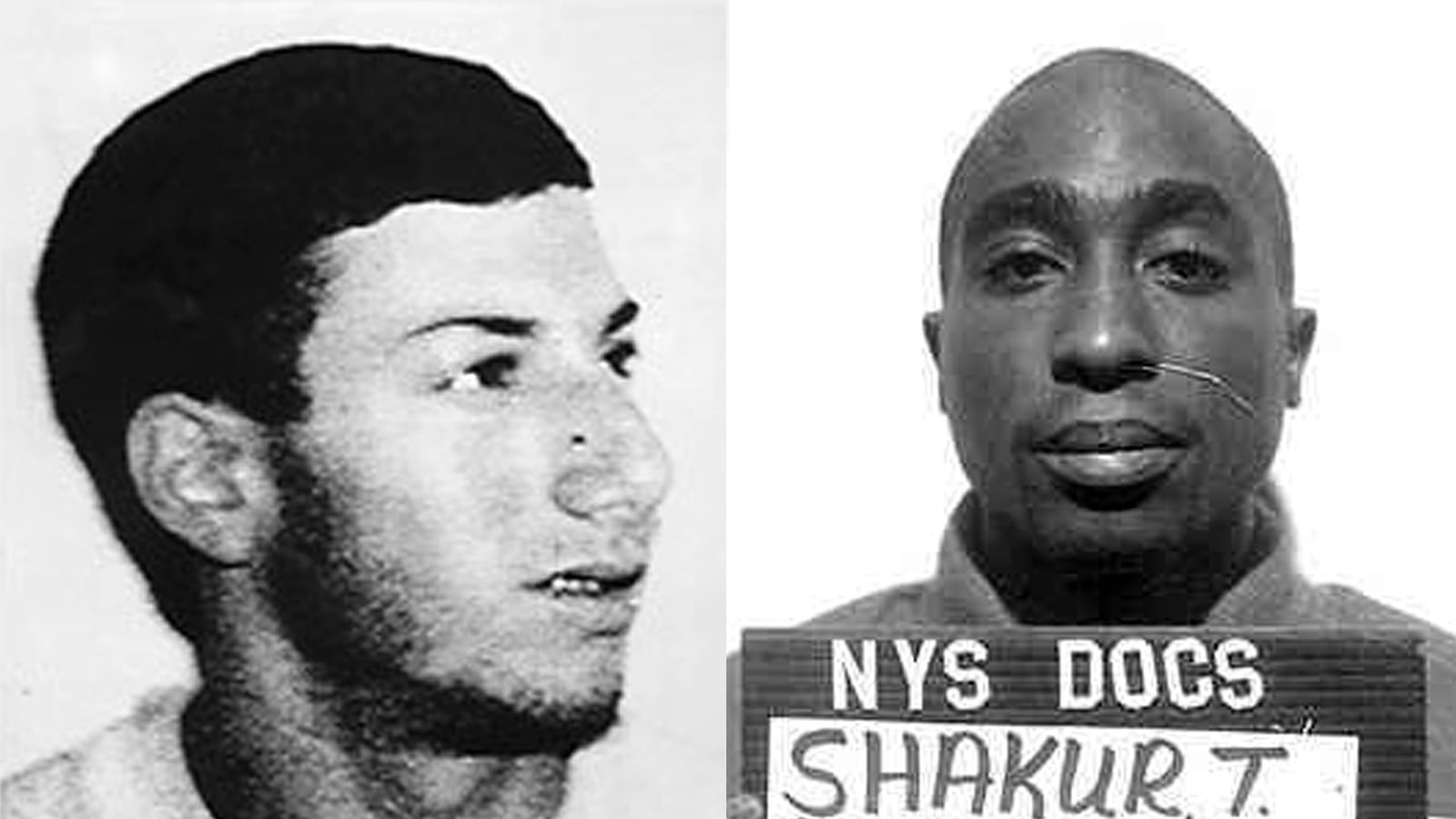

The history of friendship has few more improbable stories than that of the bond formed between Tupac Shakur and Joey Fama in an upstate New York prison two decades ago, but only reported now.

As the whole world knows, Tupac was a rap star and a kind of princeling of the black liberation movement, having been born a month after his Black Panther mother successfully acted as her own lawyer in a sensational conspiracy trial.

Fama became a symbol of blind and violent racism when he was convicted in connection with the August 29, 1989, murder of Yusuf Hawkins, a 16-year-old African American who was shot to death after he ventured with three friends into what was then the largely Italian neighborhood of Bensonhurst to see a used Pontiac G2000 listed in the want ads.

Hawkins and his pals had watched the movie Mississippi Burning before taking the subway from their largely minority neighborhood of East New York on the other side of Brooklyn. They had stopped into a candy store to ask for directions, and the clerk had looked at them as if they had surely come in to steal. Hawkins had sought to keep the peace by buying a Snickers bar.

He and his friends were a block from the address listed in the ad when they chanced to encounter a group of whites who had gathered after hearing rumors that a neighborhood girl was going to invite a crowd of blacks and Hispanics to her birthday party. A teenage boy whom police and prosecutors would identify as Joey Fama stepped up and shot Hawkins multiple times in the chest before he and his friends could clear up the misunderstanding.

Hawkins had lain bleeding in the street with one hand still holding the Snickers bar, the other clutching the hand of a neighborhood woman. He was unable to speak, and the woman asked him to blink once for yes, twice for no in reply to some questions. He blinked once when she asked if he was in pain, twice when she asked if he knew who shot him. She then inquired if he knew why he had been shot. He again blinked twice for no, as if he could not imagine that Brooklyn was so much like the Mississippi of the movie that he could be shot just because he was black.

Fama subsequently admitted being at the scene but denied being the gunman. The jury deliberated for two interminable weeks before reaching what seems to have been a compromise verdict, finding that Fama had not necessarily fired the shots but had played a part in the murder. He was sentenced to 32 years to life and consigned to one of the 258 individual cells in the Assessment and Program Preparation Unit at Clinton Correctional Facility in distant Dannemora, New York. The state Department of Correctional Services says the APPU is reserved for inmates who have high-profile cases or are otherwise “prone to victimization.”

On February 14, 1995, Tupac became the newest resident at the APPU, having been sentenced to one and a half to four years for sexual abuse. His mother, Afeni Shakur, had once said that what had made her so passionately determined to prevail during her own trial was that she had not wanted her son to be born behind bars.

That could only have added to the psychological impact of Tupac finding himself in prison four months shy of his 24th birthday. He had already been shaken by being shot multiple times the year before in what he decided was an ambush engineered by people he had trusted completely.

“I don’t got no friends,” he said afterward in a video interview. “My closest friends did me in.”

He added, “Trust nobody. Trust no-body.”

Tupac was in the yard when he was approached by a harmless-looking white prisoner his own age. Fama would later say that somebody had asked him to deliver a message to Tupac, though he would not go into the specifics.

Fama would suggest that one reason he and Tupac hit it off right from the start stems from prison being filled with people who are always looking to see what they can get from you, who have an ulterior motive.

“Everybody has another agenda,” Fama says.

Fama figures this must have been particularly intense when it came to a big star.

“Everybody had to be looking for something,” Fama says.

But Fama was one of those lucky inmates whose family and outside friends had remained supportive both emotionally and financially.

“I didn’t need anything,” Fama says. “I guess he seen that.”

Tupac did not turn away even when Fama revealed why he was in prison. That may have been partly because Fama seems remarkably innocuous for somebody so infamous, a seemingly guileless soul in a realm of schemers. A medical evaluation of him two years before the shooting noted that he had suffered head trauma in a car accident when he was 3, followed by a tricycle mishap when he was 4, leaving him with “depressed intelligence, memory and cognitive flexibility consistent with early brain injury.” He may have been a vehicle for racial hatred, but he did not seem to be a source of it.

“I didn’t start racism,” he says. “I was 18 years old. How much of a racist could I be?”

In prison, Fama had discovered that he had considerably less static with blacks than he did with whites. Trouble seemed to arise not from big issues like race but from petty gossip and backbiting.

“It’s always your own kind,” Fama says.

And just as Tupac contended that he had never sexually assaulted anybody, Fama insisted that he had not shot anybody. Both presented themselves as victims of media sensationalism.

“He said he didn’t believe the media,” Fama recalls. “I said, ‘I understand.’ I said, ‘Before I came to jail I used to read and believe everything.’”

No doubt some of the inmates had trouble believing their own eyes when they saw Tupac and Fama walking the yard together.

“I told him, ‘Probably, a lot of them are looking at us, thinking, What are those guys doing together?’” Fama says. “He says he really doesn’t care. He’s just there to do his time.”

Fama says he announced to Tupac his view of race as a result of all he had learned.

“I told him, ‘I don’t judge people by their color, I judge people by their character,’” Fama remembers.

When the inmates played street football in the concrete yard, Fama would be on Tupac’s team even though many other inmates clamored for a spot.

“He’s a celebrity,” Fama says, “Everybody wanted to be on his team.”

Neither Fama nor Tupac was a particularly gifted player.

“I’m not the best,” Fama says. “He was all right. We played.”

At other times in the yard, they just talked.

“Prison stuff,” Fama says,

At one point, the rapper spoke about Assata Shakur, who escaped from prison after being convicted of murdering a New Jersey state trooper in a shootout on the turnpike. She was on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted List and was believed to be hiding out in Cuba. She had been called the soul of the Black Liberation Army.

“He just told me that was his aunt,” Fama says.

Tupac Shakur had a steady stream of visitors despite the prison being in a frigid corner of the state so distant from New York City that it is known as Little Siberia. Malikah Shabazz, Malcolm X’s daughter, came, as did Jada Pinkett. Madonna was supposed to come but canceled after the media raised a fuss.

“He said he used to see her in the clubs,” Fama said.

One day, Tupac told Fama that he was getting a visit from the Rev. Al Sharpton.

“I heard he was involved in your case,” Tupac told Fama.

Sharpton had led a series of protest marches through Bensonhurst after Hawkins was killed. Sharpton had been preparing to embark on another march with Hawkins’s parents when a young white man stabbed him in the chest, seriously wounding him.

As Sharpton now visited Tupac in prison, the rapper told him that his jailhouse friend was not a big fan of the reverend. Sharpton asked who the friend might be and was stunned by the answer.

“JOEY FAMA?” Sharpton exclaimed.

Tupac made no mention of Fama during a long video interview. He did make clear his feelings about being incarcerated.

“Prison kills your spirit,” he said.

He spoke of being constantly told what to do and when to do it by guards who could speak to him any way they wanted.

“And you can die here,” Tupac said.

He reported that somebody had been killed in the prison just a few days before.

“Do not to come to jail,” Tupac said. “Jail is not the spot.”

On another day, Fama was getting a visit from his family when he looked over to see Tupac was having a visit from the hulking Marion “Suge” Knight, then head of Death Row Records.

“He’s there with Suge,” Fama recalls. “Suge’s like two people. He’s tremendous.”

Knight offered to post $1.4 million to bail out Tupac pending an appeal. Tupac needed only sign a three-page handwritten recording contract. He did so on September 16, 1995.

“I know I’m selling my soul to the devil,” Tupac reportedly said.

On October 9, Fama was in the yard while Tupac was on one of the outdoor pay phones. He got off and turned to Fama.

“Between you and I, I’m making bail,” Tupac said, by Fama’s recollection. “Keep it on the QT. I’m out of here tomorrow.”

Immediately after breakfast the following morning, Tupac departed.

“Take care of yourself,” Fama told him before he left. “Keep your head up.”

“If you need anything, let me know,” Tupac supposedly said.

Tupac left all his personal items behind in his cell, as if he did not want anything that he would associate with his eight months in prison.

“He didn’t take anything,” Fama recalls. “He just walked away.”

A white stretch limousine took Tupac off to a private plane that awaited at the local airport. Fama understood that the rapper might have been willing to make a deal with the devil himself to get out of prison, to sell his soul so as to save his spirit.

“I guess sometimes you got to do it,” Fama says.

Eleven months later, in September 1996, Fama heard talk that Tupac had been shot and killed while riding in a car with Knight in Las Vegas.

“I didn’t believe it at first,” Fama says. “I thought it just was a publicity stunt.”

He then saw a news report.

“This guy really is dead,” Fama told himself. “You’re with somebody and then…”

Fama continued serving his time and spoke with The Daily Beast last week as the 25th anniversary of Hawkins’s murder approached. Fama continued to insist he was not the gunman.

“I’m not saying I wasn’t there,” Fama said. “I’m just saying I didn’t shoot the guy.”

He noted that that the prosecution’s prime witnesses had included a jailhouse informant who had testified to hearing so many supposed confessions that he was known as the Pope of Rikers Island.

Fama said the prosecution’s main witness had recanted on videotape immediately after testifying, but the judge had refused to admit it. Fama now has a private investigator who says he is actively working the case.

Fama noted that his first parole hearing is scheduled for the end of 2021. He will then have to decide whether to continue insisting upon his innocence, which the board is sure to interpret as a lack of remorse.

“You got to make a decision,” Fama said. “They don’t want to hear you didn’t do nothing.”

Fama also spoke to The Daily Beast of his friendship with Tupac Shakur, which had proved to be more unlikely than he knew with the posthumous publication of a book of poems that the rapper had written at least four years before he went to prison. One of poems is titled “For Mrs. Hawkins” and is “in memory of Yusuf Hawkins.”

“This poem is addressed 2 Mrs. Hawkinswho lost her son 2 a racist societyI’m not out 2 offend the positive soulsonly the racist dogs who lied 2 meAn American culture plagued with nightslike the night Yusuf was killedif it were reversed it would be the workof a savage but this white killer was just strong-willedBut Mrs. Hawkins as sure as I’m a Pantherwith the blood of Malcolm in my veinsAmerica will never restif Yusuf dies in vain!”

Tupac must have been more surprised than anybody that he could possibly have become friends with the white killer from his poem.

Tupac often said he loved Shakespeare’s complexities. Maybe he himself possessed such intricate vision that he could play football with Joey Fama and not for a moment forget young Hawkins, who had lain dying with that Snickers bar in his hand, blinking twice to say he did not know why he had been shot.