“First off, fuck your bitch and the clique you claim…”

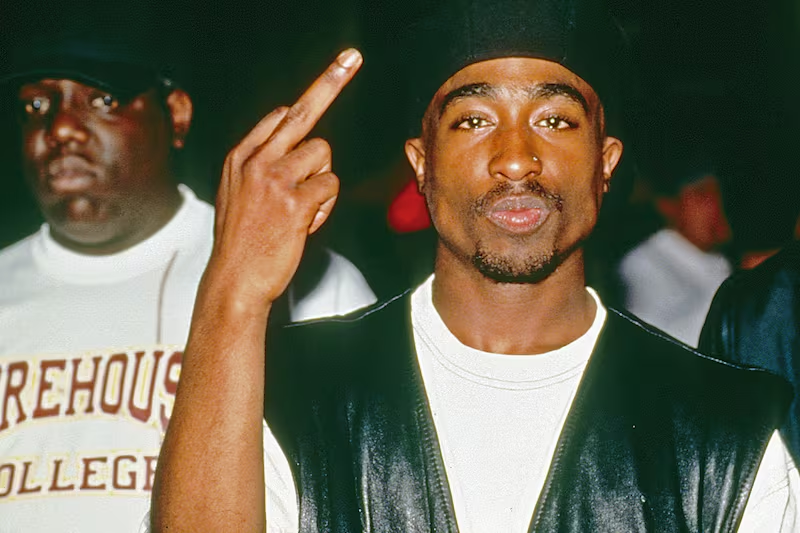

That opening line—that egregious, confrontational, hate-filled opening line—was one of the most unforgettable utterances ever committed to wax by the late Tupac Shakur. It’s been 20 years since the release of 2Pac’s scathingly brutal diss track “Hit ’Em Up,” a song that came to embody the venom behind the Death Row/Bad Boy beef of the mid-’90s and an easy reference for the antagonistic figure many saw 2Pac as in his final months on this earth.

There was a palpable sense of dread hanging over hip-hop in mid-’96.

The Death Row/Bad Boy feud had been callously hyped as an all-out war between East Coast and West Coast rappers even though there had been very little actual violence surrounding any of it at the time. But Death Row’s gangster reputation had been cemented via court cases and assault charges—and 2Pac knew both all too well, having faced numerous legal troubles since he’d burst onto the scene as a troubled-but-talented artist in late ’91.

When the Death Row roster posed on the cover of Vibe that February, the implication was clear: this was the superpower in hip-hop. And it was hard to argue otherwise. Since The Chronic dropped in late 1992, Death Row had been in the midst of a strong run: Snoop’s Doggystyle arrived in fall 1993, the Above the Rim soundtrack in spring 1994, the Murder Was the Case soundtrack/film later that year, and Tha Dogg Pound’s Dogg Food in fall 1995. And 2Pac released his smash double-disc All Eyez On Me in February 1996.

For some perspective, their rival Bad Boy Entertainment had only one bona fide rap star in the Notorious B.I.G. at the time. Craig Mack had been the label’s first success but it had been two years since he hit big with “Flava In Ya Ear” and Mack was looking more like a one-hit wonder by then. Future Bad Boy hip-hop artists like Ma$e and the LOX wouldn’t release albums until 1997. Most of Bad Boy’s success throughout 1995 and 1996 would come via R&B hits by acts like Faith, Total, and 112. As it pertained to hip-hop, at this particular juncture, Death Row ruled the roost.

But the cracks were beginning to show.

Time Warner had severed ties with Interscope following the controversy surrounding Dogg Food. Tha Dogg Pound’s debut was the last in a series of albums and incidents that had drawn contempt for gangsta rap and the artists who produced it, and Time Warner sold its 50 percent interest in Interscope back to the label after public outcry had reached a fever pitch. Also, Snoop was just resuming his hip-hop career following a lengthy murder trial that contributed to his notoriety but stalled his momentum following the multi-platinum success of Doggystyle and Murder Was the Case. Perhaps most notably, label mainstay and co-founder Dr. Dre had defected from Death Row in March—shortly after that infamous VIBE cover hit shelves—to launch his own Aftermath Entertainment, sans label head Suge Knight.

And in the midst of all that instability, there was the incendiary Tupac Shakur.

Death Row was clearly in a state of flux, with Dre’s unexpected departure, the sudden arrival of 2Pac, and the way that Suge clearly centered Pac as the label’s biggest star—a title that had been held by Snoop Doggy Dogg for three years running. Suge was no fool; coming out of prison, 2Pac was the most talked-about rapper in the industry and signing with Death Row made him even more notorious (no pun intended) than he’d been in the previous four years of his career.

Pac had clearly been emboldened by his association with the most feared label in rap.

The thoughtful, somber 2Pac that had released Me Against the World in the spring of 1995 while incarcerated for a sexual assault conviction seemed to disappear after Suge Knight posted his $1.4 million bail in fall 1995 and signed him to Death Row. All Eyez On Me had announced Pac as the new face of Death Row and the most confrontational and combustible personality in hip-hop. He was unapologetic and unrestricted—even with the specter of returning to prison looming pending appeals. 2Pac didn’t give a fuck anymore. And with he and Suge sharing a mutual contempt for Bad Boy Entertainment, Sean “Puffy” Combs, and the Notorious B.I.G., Pac knew exactly where to focus his rage.

As even the most casual hip-hop fan knows, 2Pac had been shot in the lobby of Quad Studios in Manhattan in November 1994—just before he was due to go to trial for the sexual assault charge. In the aftermath of the violence and his subsequent conviction, he made it clear that he believed Biggie and Puffy—the biggest star and founder of Bad Boy Entertainment, respectively, and former friends of Pac’s—had conspired or were aware of an attempt on his life that night at Quad City. To make matters worse, shortly after the incident B.I.G. released the track “Who Shot Ya?”—a song that Pac perceived as mocking what had happened to him.

“I wrote that muthafuckin’ song way before Tupac got shot,” Biggie told Vibe later. “It was supposed to be the intro to that shit Keith Murray was doing on Mary J. Blige’s [My Life] joint. But Puff said it was too hard.”

But Pac didn’t believe that story—and didn’t seem to care even if it was true: “Even if that song ain’t about me. You should be, like, ‘I’m not putting it out, ’cause he might think it’s about him.’”

So after the bailout, the signing, and the success of All Eyez On Me, Pac had to get something off of his chest and cement his status as the biggest—and possibly most-feared—rapper in hip-hop. He recruited his associates and protégés Dramacydal for the record. Rechristened The Outlaw Immortalz (subsequently just The Outlawz), the New Jersey natives had already appeared under their former moniker on Pac songs over his previous two albums, but as The Outlawz, they would make a far more memorable impression on “Hit ’Em Up.” Hussein Fatal, Khadafi and E.D.I. Mean contributed scathing verses aimed at Biggie and Puff, but when the song was recorded it was 2Pac’s venom that seemed the most pointed, his rage the most real.

“All you niggaz gettin killed with ya mouths open Tryin’ to come up offa me, you in the clouds hopin’ Smokin dope it’s like a sherm high niggaz think they learned to fly But they burn motherfucker, you deserve to die…”

Pac had already claimed to have slept with Biggie’s estranged wife, Bad Boy singer Faith Evans, and mocked his rival’s early days “when I used to let you sleep on the couch.” There was a personal edge to his anger that led to the song’s producer, the late Johnny J, declaring that he never wanted to work on anything like “Hit ’Em Up” again. Throughout the song, he took aim at Bad Boy associates Junior M.A.F.I.A. (“Some mark-ass bitches”) and Lil Kim (“Quick to snatch yo’ ugly ass off the streets.”) And in the infamous outro, Pac exploded in a rant against a host of others he’d taken issue with, from Prodigy of Mobb Deep (“Don’t one of you niggas got sickle-cell or something?”) to Chino XL (“Fuck you, too!”)

When the song was recorded, Pac and the Outlawz played it for some unexpected guests in the studio.

“Goodie MOB was up in there that night,” E.D.I. Mean explained to VladTV in 2014. “They came through right when we finished it. They were some of the first people to hear that record. They was just standing there like, ‘Oh shit.’ I’m sure—my boy T-Mo told me he was happy to hear that shit. Not happy to hear that we were going at anybody, he just liked the song. But for the most part they were just standing there like ‘oh shit.’

“I was so hungry and just eager to prove myself at the time, I was just happy I made the record and my eight bars was solid,” explained E.D.I. “Everybody on that record was raw at what they do. Hussien Fatal was one of the best rappers from Jersey for years prior to even getting with us. And the late, great killa Khadafi was nasty in his own right. Then you got Pac on there with two verses.

“The record was coming form a hip-hop standpoint as far as classic diss records,” he continued. “We was drawing from [Boogie Down Productions’] ‘The Bridge Is Over,’ [Ice Cube’s] ‘No Vaseline’—those were the two records that, at the point, were the pinnacle of diss records. The whole Dre and Eazy beef was classic records that come up out of beef, unfortunately. That’s where we was coming from. It wasn’t about running up on niggas and actually trying to physically harm them. It was like yo—Pac was back and this is how he’s saying it.”

When the song dropped, it was too hot to touch. Fans eager for more East/West drama ate it up—it arguably drove up single sales of the A-side “How Do U Want It.” But there was also criticism that this particular diss track was taking things too far. Pac scoffed at the notion in an interview with Vibe.

“Fear got stronger than love, and niggas did things they weren’t supposed to do,” Pac stated. “They know in their hearts—that’s why they’re in hell now. They can’t sleep. That’s why they’re telling all the reporters and all the people, ‘Why they doing this? They fucking up hip-hop’ and blah-blah-blah,’ cause they in hell.”

Mobb Deep’s Prodigy was taken aback by the diss. “I was, like, ‘Oh shit. Them niggas is shittin’ on me,” he told Vibe. “He’s talking about my health. Yo, he doesn’t even know me, to be talking about shit like that. I never had any beef with Tupac. I never said his name. So that shit just hurt. I’m, like, ‘Yeah, all right, whatever. I just gotta handle that shit.’” (Mobb Deep would release a response in “Drop a Gem On ‘Em” from their 1996 album Hell On Earth, shortly before 2Pac’s murder in September.) Biggie would allude to the beef on his final album, 1997s Life After Death, but, aside from a famous one-liner on Jay Z’s “Brooklyn’s Finest,” there was never an “official” response record that explicitly called out 2Pac by name.

In the wake of Shakur’s murder, “Hit ’Em Up” would become a chilling epitaph for a feud that seemed to spiral out of control—even more so after the Notorious B.I.G. met a similar fate in March 1997. Taken on its own merit, it’s one of the greatest diss records in hip-hop history; but attached to the moment, it was a lot more than that. Something more volatile. Something more dangerous. Twenty years later, its legacy is a bit muddy—but it’s a part of the indelible persona that was Tupac Shakur; a riveting portrait of a young outsider’s rage and fury and a testament to his charisma and power. There were people who hated Biggie after that song was released just because of that song. Maybe 2Pac didn’t fully understand the power he wielded or maybe he finally got it later but was running out of time. Regardless, it’s one of the most compelling rap records ever recorded.

Even if it might be compelling for the all the wrong reasons.