The MetroPCS store on the corner of Florida and Georgia avenues in Washington, D.C., sits at the heart of the Shaw neighborhood. Once surrounded by boarded homes, fast food joints, and Howard University, the store, which sells cellphones and electronic accessories, is now wedged between luxury condos, hipster cafes, and a concert venue.

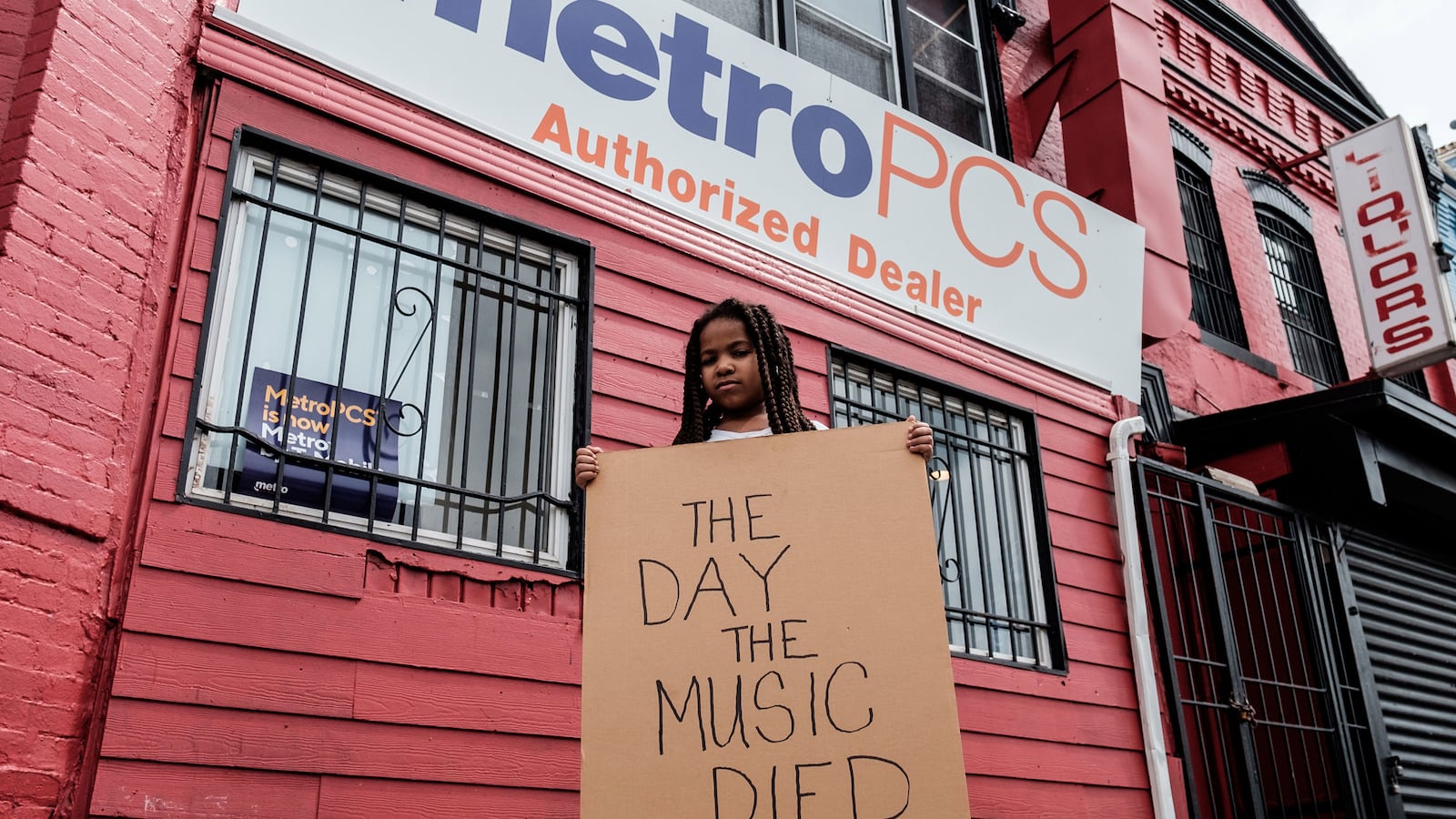

For 25 years, one thing hadn’t changed: Go-Go, a funk-like music unique to the district, blasting from the store. That was until a noise complaint threatened to shut it down.

“It started with condo residents writing letters to the owner, then noise complaints to police,” says Natalie Hopkinson, a Howard University professor and advocate for the store’s owner, Donald Campbell. “When they didn’t get their way, the residents threatened to sue.”

At first they were successful. Soon executives from T-Mobile, Metro’s parent company, notified Campbell that the music should be shut off. Corporate executives didn’t anticipate, however, that appeasing condo residents would ignite a firestorm of backlash from D.C. natives, leading to anti-gentrification protests. More than 50,000 people signed a petition demanding that the Go-Go music resume, and by late April dozens of protests—including live concerts in front the store—became a rallying call for black natives to take back D.C., at one point nicknamed “Chocolate City.”

After nights of demonstrations, T-Mobile CEO John Legere announced that the Go-Go music would resume. But the incident is one example of how communities in transition create cultural clashes between mostly black and low-income longtime denizens and rich, white transplants.

“Everyone thought it started from one noise complaint, but this was a coordinated campaign to shut the store down,” Hopkinson says. She says MetroPCS had already received multiple police visits, each one requiring the store’s employees to prove the volume was within regulation.

“That’s harassment, which creates unnecessary interaction between law enforcement and people of color,” she says.

The store’s owner isn’t the only one facing increased police scrutiny. Across the District of Columbia, black natives complain that with each new resident comes increased targeting by law enforcement tasked with keeping their communities safe.

“Gentrification and police work can feel like they have the same goal,” says Paul Butler, a Georgetown University professor and former federal prosecutor. “Many white people, when they feel threatened by African-Americans, call 9-1-1 because they know the state will respond to their racial anxiety.”

According to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, Washington, D.C., experienced the most “intense” gentrification of any major city in the country. Between 2000 and 2013, 40 percent of all low-income neighborhoods in D.C. experienced gentrification, displacing more than 20,000 African Americans. The District ranks third in the number of neighborhoods to transform overall.

Although African Americans remain the city’s largest ethnic group, their numbers declined since the 1970s, when a 70 percent population earned D.C. the nickname “Chocolate City.” A black majority ended in 2011, and the African-American population stands at 47 percent today. Butler says that rapid change can make people of color vulnerable to the prejudices of their new neighbors.

“[These studies] reflect the experiences of black Americans everyday and the fact that police are laser focused on them,” he says. “It feels like police are not there to serve and protect their communities but are part of the apparatus making them feel unwelcome in the neighborhoods they’ve been in for generations.”

Open The Government, a consortium of government transparency groups, and the ACLU, examined arrest data from the Metropolitan Police Department between 2013 and 2017, finding sharp disparities in arrests for minor offenses like noise ordinances, driving without a license, and marijuana consumption. Black residents were 47 percent of the city’s population but 86 percent of all arrests—a rate 10 times that of white people.

“The complaints we’re getting from community members are of officers stopping them or arresting them without probable cause,” says lead attorney Michael Perloff. “By and large the people complaining to us are overwhelmingly black.”

Disparities are citywide. Black people are disproportionately arrested in every D.C. neighborhood no matter its racial makeup or crime rate—making any link to gentrification difficult to determine. One element preventing the researchers from making that connection to is how many arrests stem from calls to 9-1-1 or 3-1-1.

“The Metropolitan Police Department is not doing a good job collecting data on stops overall,” Perloff adds. Metro police are required to provide data as part of a transparency law enacted in 2016. But Perloff notes researchers acquired the data via the Freedom of Information Act but are suing Metro police over what they consider further non-compliance.

Recent cases of police stopping black people for moving into an apartment or barbecuing originated from a 9-1-1 call. While the report’s researchers can’t correlate arrests to gentrification, research does suggest that changing communities nationwide lead to increased policing of black people.

According to Brenden Beck, assistant professor at the University of Florida who studies sociology, criminology and law, calls to police tend to be higher in gentrifying communities. That’s because as richer, mostly white transplants permeate once black and brown neighborhoods, with them come new standards and expectations. Cultural differences can result in new residents calling law enforcement to report neighborhood norms as nuisances.

“Early research already shows a pretty clear connection between gentrification and increased stops or arrests,” he says. “Whether looking at gentrification from a class, race or housing-market standpoint, it’s pretty clear that as race and class tensions get exacerbated, 3-1-1 calls to the police increase.”

By 2015, natives of D.C’s historic H-Street Corridor met with Metropolitan Police Department complaining of increased racial profiling and unwarranted stops. There, both law enforcement and longtime residents implored new residents to stop calling police on their black neighbors for mundane activities. Then-police chief Kathy Lanier promised better community relations; Hopkinson smirks when reminded of that meeting.

Instead, she recalls a 2010 press conference when Metro police credited a drop in crime to their crackdown on the local Go-Go scene. Her book, Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City, details how Go-Go has been stigmatized to perpetuate anti-black stereotypes of violence and danger.

“Even back then law enforcement’s rhetoric positioned itself as doing the work of gentrifiers,” she says. “It’s reinforced the power they now feel they have to take over parts of the city by weaponizing their whiteness and newness.”

The condo community’s campaign to mute the MetroPCS store may have failed, but Hopkinson still worries. While one native business stays open, more shut down or are under threat.

Last week was the first annual D.C. Natives Day, a city holiday commissioned by the mayor in response to the anti-gentrification protests. For many transplants, it was their first exposure to the rich, black history that has made the city a go-to destination in the first place.

Justin Johnson, an artist whose protests, combined with a social media campaign called #DontMuteDC, sparked an anti-gentrification movement, says Go-Go is for everybody, pointing to Metro Police’s community band as an example of engagement without the erasure. The band, whose make up is primarily black, D.C. natives, has performed in area schools since the 1970s, but only recently relaunched as a form of community engagement.

“We welcome anybody here in D.C.,” he says. “But learn about us, learn our history and our culture because we ain’t going nowhere. Cracking down on Go-Go culture and D.C. natives as a whole just makes us fight harder to stay.”