It was being whispered around that Satan was in Vienna incognito, and the thought came into my mind that it would be a great happiness to me if I could have the privilege of interviewing him. “When you think of the Devil” he appears, you know. It was past midnight, I was standing at the window of my work-room high aloft on the third floor of the hotel, and was looking down upon a stage-setting which is always effective and impressive at that late hour: the great vacant stone-paved square of the Morzin Platz with its sleeping file of cab-horses and drivers counterfeiting the stillness and solemnity of death; and beyond the square a broad Milky Way of innumerable lamps bending around the far-reaching curve of the Donau canal, with not a suggestion of life or motion visible anywhere under that glinting belt from end to end. If the square and the curve were dim or dark, the impressiveness would be wanting; but the multitudinous lights seem to belong properly with life and energy and the roar and tumult of traffic, and these being now wholly absent, the resulting impression conveyed to the spirit is that they have been suddenly and mysteriously annihilated, and that this brooding midnight silence and solemnity are the signs and symbols of the tragedy that has happened.

Satan would not allow me to take his hat, but put it on the table himself, and begged me not to put myself to any trouble about him, but treat him just as I would an old friend.

Now, with a most strange suddenness came an inky darkness, with a stormy rush of wind, a crash of thunder and a glare of lightning; and the glare vividly revealed the figure of a slender and shapely gentleman in black coming leisurely across the empty square. By his dress he was an Anglican Bishop; but I noticed that he cast a shadow. That gave him away, as Goethe phrases it; for by the ministrations of lightning no legitimate Anglican Bishop can do that—nor can any other earth-born creature, for that matter. This person was Satan. I knew it. It was in his honor that the sudden storm had been summoned and its thunders delivered in salute. It was inspiring, it was uplifting, this sublime ceremonial. If I had been a monarch it would have spoiled, for one while, my satisfaction in my little artillery salutes. And yet I would have tried to be properly philosophical, and ease and content myself with the reflection that the honors had been fairly and justly proportioned to the difference existing between Satan’s importance and mine, I being but a passing and evanescent master of a limited patch of empire, and he the long-term master of the majority of the human race.

I had that glimpse of Satan and his shadow, and the next moment he was by my side in the room. He did not embarrass me. Real royalties do not embarrass one; they are sure of their place, sure of its recognition; and so they bear about with them an alpine serenity and reposefulness which quiet the nerves of the spectator. It is the prerogative of a viscount or a baron to make a person feel small, and of a baronet to extinguish him.

Satan would not allow me to take his hat, but put it on the table himself, and begged me not to put myself to any trouble about him, but treat him just as I would an old friend; and added that that was what he was—an old friend of mine, and also one of my most ardent and grateful admirers. It seemed a doubtful compliment; still, it was said in such a winning and gracious way that I could not help feeling gratified and proud. His carriage and manners were enviably fine and courtly, and he was a handsome person, with delicate white hands and an intellectual face and that subtle air of distinction which goes with ancient blood and high lineage, commanding position and habitual intercourse with the choicest society. The usual portraits of him are but resemblances, nothing more. They are very inaccurate. None of them is recent. The latest is as much as three hundred years old. They were all made by monks, and from memory; for the monks did not tarry. The monk was always excited, and he put his excitement into the picture. He thus conveyed an error, for Satan is a calm person; aristocratically calm and self-possessed. Satan’s face is notably intellectual, and fine, and expressive. It suggests Don Quixote’s, and also Richelieu’s, but it is not so melancholy as the one nor so austere as the other; and neither of those grand faces has the winning quality which is the immortal charm and grace of Satan’s.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

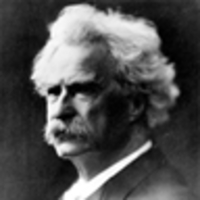

Extracted from Who is Mark Twain? by Mark Twain. © 2009 With permission from the Publisher, HarperStudio. http://twainia.com/contest/