Voters in L.A.’s San Fernando Valley face an unusual choice in California’s primary election on Tuesday. Should they cast a ballot for a long-time liberal Democratic incumbent? OK, which one?

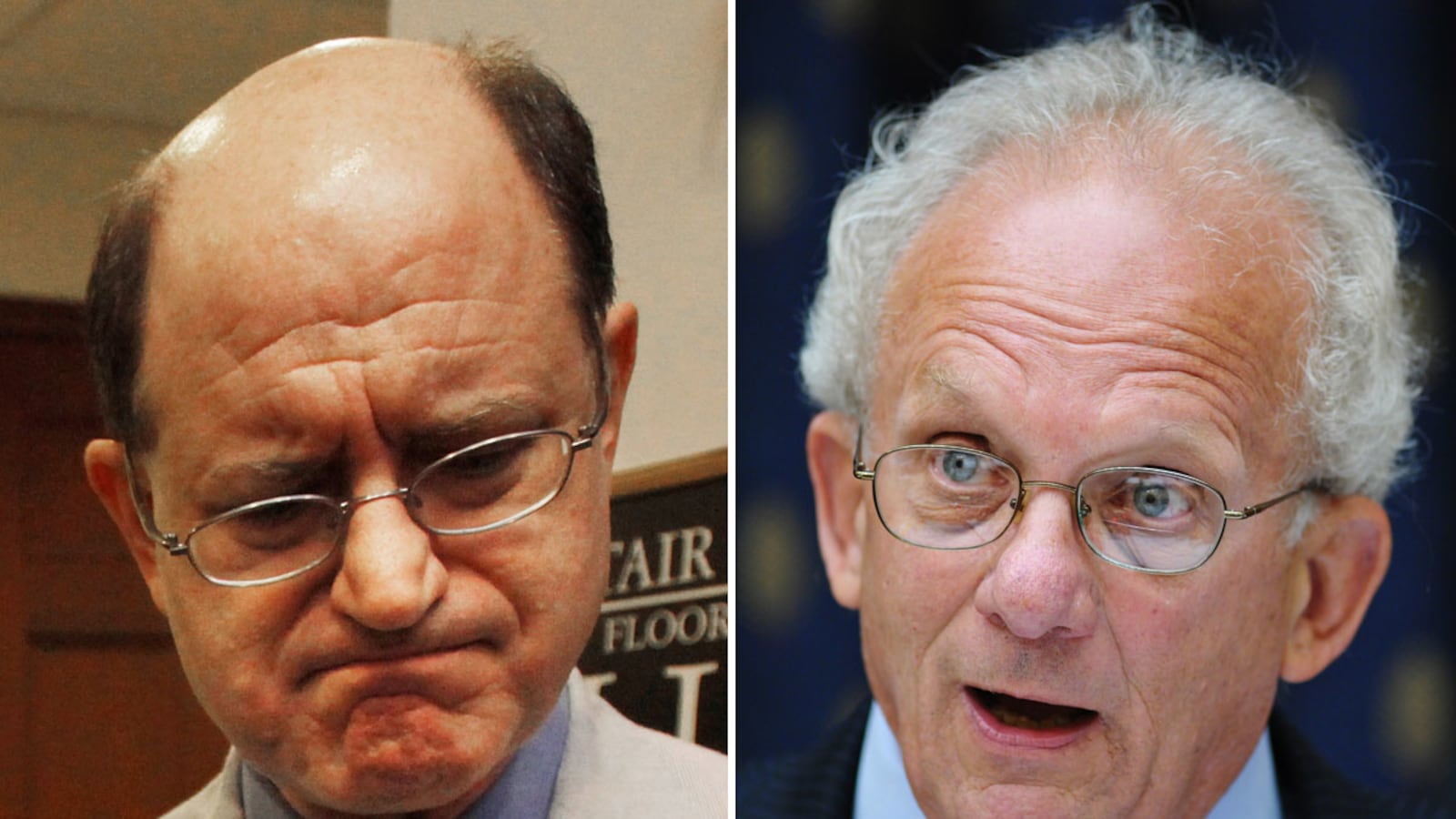

In an accident of redistricting following the 2010 Census, two popular Democratic congressmen with 44 years’ combined tenure are locked in a bitter fight to see who’ll be elected in the new 30th Congressional District. Brad Sherman and Howard Berman, both Jewish, share similar voting records and even serve together on the House Foreign Affairs Committee. But the Sherman-Berman race in the Valley is beginning to look like the History Channel’s wildly popular “Hatfields & McCoys”—a harsh feud of survival fought not with sixguns, but near daily charges and counter-charges and millions of dollars in full-color mailers and TV ads.

“This is nuclear war,” says University of Southern California political scientist Sherry Bebitch Jeffe. “You won’t see a congressional campaign that costs more or gets any nastier.”

Elected in 1996, Brad Sherman, 57, sells himself as a hard-hitting retail politician who constantly flies back home from Washington, D.C., and shares with constituents what he calls “Valley values.” He opposed the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) bailout in 2008, and blasts most free-trade agreements as bad deals for his constituents. He paints Berman as a Washington insider tied to special interests and super-PACs who’d rather jet off on foreign jaunts at taxpayer expense than pay attention to actual voters.

“I’ve done 160 town halls,” Sherman tells The Daily Beast after a Memorial Day weekend coffee-with-the-congressman event at the Chatsworth home of a retired aerospace engineer. “(Berman) hasn’t had the time to do them because he’s done 163 junkets.”

Berman, 71, is a professorial legislative insider whose specialties include foreign policy, environmental legislation, and digital antipiracy issues to protect Hollywood’s music and movie industries. He acknowledges he’s a low-key campaigner: he says his last hard-fought primary came with his first run for office, back in 1972. “Until this race, I haven’t spent a lot of time promoting what I’ve been doing in this job,” he admits in an interview. “But I’ve changed my nature. I’ve had to.”

Berman says that his record of accomplishments outstrips his opponent’s. “If the voters look at my record of producing for the San Fernando Valley, it’s not a close call,” he says. He describes Sherman as a grandstander who prefers “gimmicks” to concrete achievements. “The man has been there 15 years,” Berman says. “He’s written three bills that have passed, and two of them named post offices.”

Sherman and Berman represent the tension between the Valley’s insularity and cosmopolitanism. Home to 1.5 million residents and separated from the rest of L.A. by a mountain range, the Valley was the quintessential post-war commuter suburb. Its identity has remained distinct from the rest of Los Angeles—more spread out, more relaxed, less glitzy. Valley culture gave birth to Valley Girls in the ‘80s and to voter discontent that, a decade ago, spawned a secession movement that failed.

The “818” may lack star power, but thousands of Valley residents work in the music, film, and TV industries; Disney, Warner Bros. and Universal are all based there. And in recent decades, the Valley has become ethnically polyglot and more complex. Formerly whitebread suburbs have been enriched with immigrants from all over—Latinos, Thais, Greeks, Armenians, Indians, Filipinos, and Iranians. Now, pho joints and Korean restaurants vie with In-N-Out Burger and Jewish delis.

Until redistricting threw the two congressmen together, the Valley was big enough for both men. Berman and Sherman reside only three miles apart, and had served adjoining districts that fit together like a lock and key. But when the state redistricting commission created a Latino district from parts of Berman’s old stomping grounds, he and Sherman found themselves fellow residents in the new 30th. The numbers in the new district favor Sherman: more than half the registered voters come from his old district, but only 25 percent from Berman’s. (The balance comes from a third district.) With the battle lines drawn, the Jewish Journal—which is covering the race even more heavily than L.A.’s two dailies—has taken to running a standing headline on its campaign blog that reads, “Berman v. Sherman: Two Jews, One District.”

Given that freeways are the lifelines in these parts, connecting neighborhoods like Northridge, Reseda, and Tarzana to the rest of the world, it was perhaps inevitable that the two Foreign Affairs Committee veterans would wind up squabbling over them. Both are taking credit for an expansion of the 405 Freeway, a long-clogged main artery connecting the Valley to West L.A. The 405 is so essential—and so crowded—that when it was shut for two days of bridge repairs last July, local officials dubbed the stoppage “Carmageddon.”

On a recent “Accomplishments Tour” stop, Berman lured reporters to a mall parking lot overlooking the 405. Backed by Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, Berman took credit for kickstarting the billion-dollar expansion and widening project by securing the first dollars of federal funding. “If voters want an effective congressman who is more likely to make things happen back in Washington, I think I’m the candidate,” Berman said during the tour. For his part, Sherman counters that he lobbied for and won key state funds.

Of the two candidates, Berman is the better connected: he’s been endorsed by both of California’s senators, 24 of 26 of its congressional Democrats, all five county supervisors, and Mayor Villaraigosa. (“It really wasn’t a difficult decision,” Villaraigosa told reporters at the 405 event.) Berman is also the Hollywood candidate. When President Obama came to town for a fundraiser last month, Berman rode with him from the airport to George Clooney’s home. Berman was honored for his antipiracy work at this year’s Grammys, and moguls Jeffrey Katzenberg, David Geffen, and Steven Spielberg hosted a fundraiser last year that netted $1.6 million. Betty White and her Hot in Cleveland costar Wendie Malick cut a TV ad endorsing him, a play for the senior demographic that dominates low-turnout elections.

Sherman’s appeal is more populist and relentlessly local. Almost all of the local elected officials in the 30th District have endorsed him. L.A. City Councilman Dennis Zine says Sherman’s office helps his constituents, and that the congressman is omnipresent at community events. When Zine hosted an awards event honoring local cops and firefighters, most pols, including Berman, sent staffers to cover. Not Sherman. “He came himself,” Zine says admiringly. “He connects with people.”

At Sherman’s recent Chatsworth event , his staff lays out Brad Sherman combs (he’s bald—get it?), and the candidate jokes that he’s “Brad Sherman from America’s best named city, Sherman Oaks.” He explains that he voted to cut college-loan rates for Valley kids and raise mortgage-loan limits to give Valley homeowners access to cheaper mortgage rates. He says that while Berman supported the banks, he led the congressional fight against TARP. “We forced dramatic changes,” Sherman says. “That, I think, is the most important thing I’ve done in Congress.” Video cameraman Scott Fain, 54, likes what he hears at the event. “I’m still undecided, but I like the fact he stood up against the TARP deal,” he says.

Though Berman has probably outspent Sherman—the two campaigns combined have burned through at least $4 to $5 million—experts give the edge on Tuesday to Sherman, in part because so many of his old voters are in the new district.

But the fight won’t end on June 5. California’s new “jungle” open-primary law dictates that the top two finishers in the primary, regardless of party, will face off in November’s general election. Which means more bickering, more feuding—and a final tally that may run to $10 or $12 million. For better and worse, Sherman-Berman 2 may be one sequel that matches the original.