Not long after I acquired this animal, Stanley ate the ass out of my pants. He was ten years old then, and we'd picked him up—rescued him, as they say—from a shelter not too far from Hollywood. We—Mrs. Nale and I—had been to a romantic Northern Italian restaurant and I did not notice the spilled fettuccine alla Bolognese as I slid into my seat in the booth. As I understand it—and here is a dating tip if you are out for a night of romance and want her to know that you’re no amateur when it comes to expensive restaurants—the difference between Northern Italian cuisine and Southern Italian cuisine is that in the south they don’t sit on the pasta.

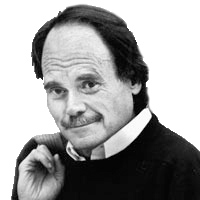

Stanley is what is called a yellow lab. About 90 percent anyway. His coat is in fact a pale shade of yellow and he likes to keep a three-day beard speckled with white, about like Harrison Ford. Who is also from Hollywood. Unlike Harrison, Stanley perpetually tilts his head in that way dogs tilt when they are puzzled. A sweet old dog that nobody else wanted.

I found my pants in the morning in a tangle on the floor in the next room. A moment of pause—could the romantic dinner have been that romantic? Could I have forgotten? Had I better keep my mouth shut until I remember?—I pushed my legs through the leg holes and slipped on my pants and shoes for our regular morning visit to the dog park. We are a three-dog household, and the younger two, as always, hit the open door at the same time, a two-dog logjam. I help Stanley up into one of seats where he can press his nose into the side window, and a spot of fog the size of a baseball comes and goes as he breathes.

I slide into the cab with him—wait, that is not exactly what happens. Exactly what happens is that I get in and try to slide over behind the wheel but I stick to the seat. This may be hard for Montana readers shoveling their trucks out of snow banks this morning to picture, but in the part of the country where I live—San Diego—most of the time, if you don’t have a reason to sit down, you could walk around all day with the ass eaten out of your pants and never know it. And even after you sit down—even after you lift one side and feel with your own fingers—it takes a long time to put it together. There . . . is . . . no . . . ass . . . in . . . my . . . pants.

*****

We have a serious talk, and he sees my point and I see his. Eighteen months goes by, and the eating the ass out of my pants was just a one-time mistake. He acknowledges the error and—not knowing where Stanley was before I got him—I can see how it happened. New house, new rules, right?

Stanley thinks television is rotting my mind. You turn on the box, there is nothing to eat. No leash to hook up and walk around the block, nothing to smell, or scratch. He circles a cushion on the floor and begins to settle in—a 747 nestling into the gate, and out of nowhere his body goes one way and his legs go the other, and he hits the floor hard.

This is as fast as I have moved in quite a while. I look down, he looks up. I can see he’s confused, but I check his legs, etc., and he doesn’t seem hurt. Still, I get him back on his feet and he stumbles, again and again, his eyes everywhere at once, his head more tilted than usual. Then I get him to lie back down.

Note: There are expressions I am learning to avoid because they are clichés and people read over them without thinking about what they mean. One of them is, worried sick. This, unfortunately for American literature, etc., is exactly what I am, so Shakespeare can shove it. There, I feel better.

*****

In the morning Stanley and I go to the veterinarian. The vet kneels beside Stanley, looks into his eyes, and strokes his ears. I like the vet, Stanley likes the vet. "Mileage," he says. The condition is a vestibular syndrome, or more commonly, “old dogs’ disease.”

Old dogs' disease, says the veterinarian, is common in old dogs. This is 90 dollars worth of advice in California. On the good side, the condition is “self-limiting,” as they say in the medical community, meaning it should clear up on its own. It’s the should that makes me nervous.

It occurs to me then how all this has stolen up on us. If Stanley was ever fast, he isn't anymore, even when I can talk him into walking. Or getting out of bed. A lot of times lately he’s passed on the trip to the park. He’s gained about 20 pounds but it looks better on him than it does on me. In fact, with the salt and pepper in his beard, the weight looks distinguished.

In any case, while we wait for his condition to clear up, I follow him everywhere; help him up and down, propping him up when he shakes his head. Gradually he is standing straighter, tipping less, and we begin to walk. It has been a long time convalescing and for him the world is brand new.

We are halfway to the cross street when it happens again. A little stretch of uneven pavement, a tremendous fall. This time howling, pitiful howling, and there’s nothing I can do to make it stop. Eventually, though, the worst of it fades. The sun is blinding, and in the shadow caused by the animal’s head I look up and see him standing over me, looking worried. And maybe a little embarrassed.

By the time we get to the doctor, my ankle is twice its normal size. He says I'll need surgery. I've torn a tendon sheath, and whatever that is, you don’t want to tear it.

Surgery-wise, I think we’re waiting for parts. Or the swelling to subside. Something like that. For now, the tendons snap back and forth over bone when I walk, except when I’m wearing a plastic brace.

*****

The backyard is two tiers, with a steep drop of ten or twelve steps between them. One night under a full moon, about three or so, I let Stanley out to take care of his business, as they say. As he squats his body goes one way and his legs go the other, and when I get to him he is laid out at the bottom of the hill, and we sit there a little while under the moon, until he catches his breath and I catch mine.

Once again he’s unhurt and I can feel my ankle swelling, killing me, and while we sit together, getting ready for the long walk back up the hill, we talk, Stanley and I, about what a fragile world it is.