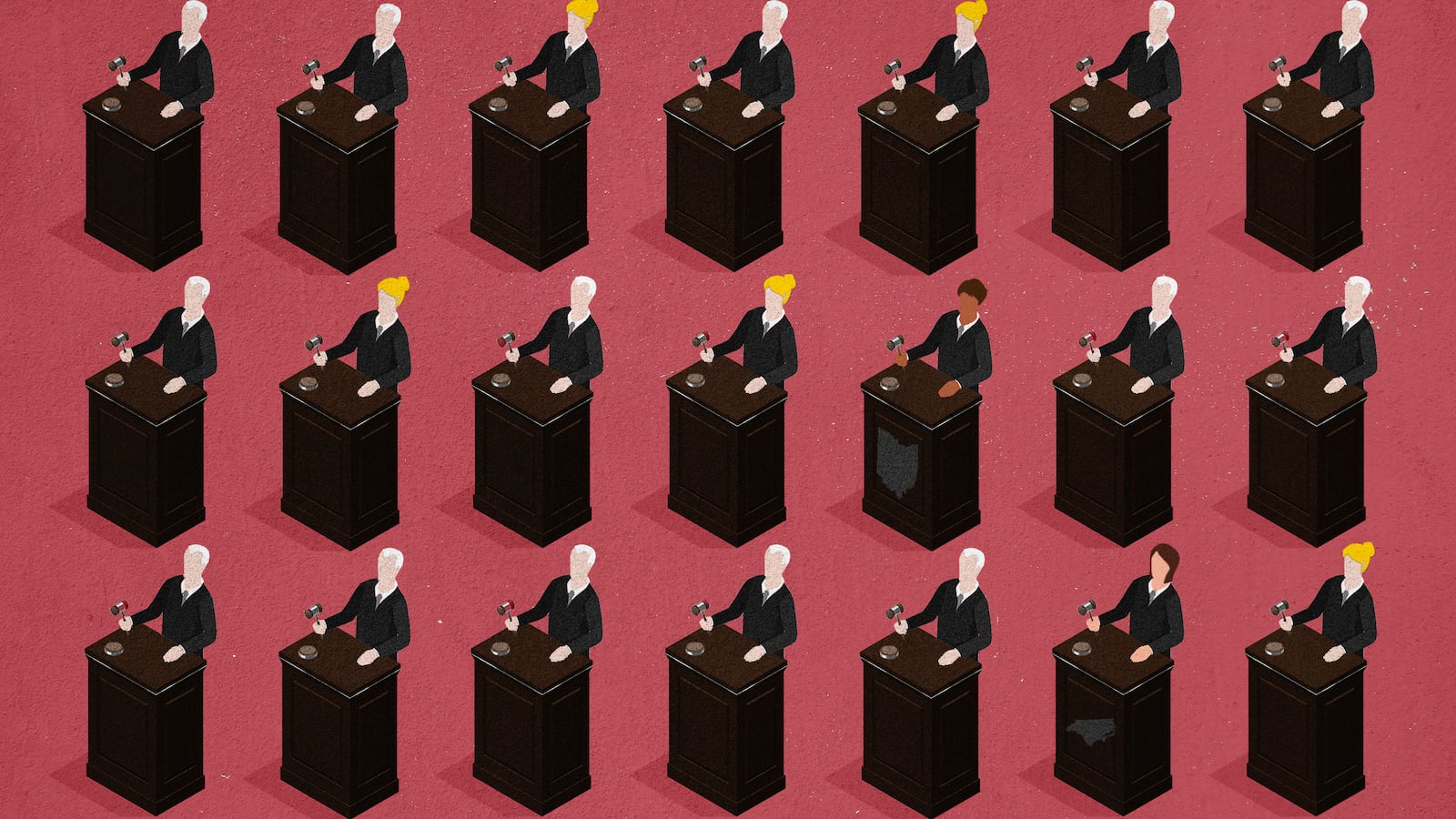

This week, civil rights attorney Anita Earls in North Carolina and appellate judge Melody Stewart in Ohio became the first non-incumbent women of color to win a state supreme court election in at least 18 years—and Stewart the first African-American woman ever elected to the Ohio Supreme Court. It’s a breakthrough for judicial diversity, but it also reveals just how little progress we’ve made in making the bench reflect the communities they serve.

With intense political contests up and down the ballot this year, you’d be forgiven for missing that 29 states held elections for their state supreme courts Tuesday. While these courts don’t draw the same headlines as the U.S. Supreme Court, they’re just as likely to impact our lives. Ninety-five percent of all cases are filed in state court, and state supreme courts are the final word for most state law issues, ruling on everything from environmental regulations to reproductive rights.

That’s partly why the lack of diversity is so appalling. In 2016, nearly half of all state supreme courts did not have a single justice of color – and nearly 70 percent did not have a single woman of color serving as a justice. This lack of diverse perspectives can impoverish judicial decision-making and harm public confidence in the objectivity and fairness of the judicial system.

While a lack of judicial diversity is an issue in states that appoint justices as well as in states that elect them, we at the Brennan Center looked specifically into where diverse candidates might be facing hurdles in the 22 states where justices must compete in contested elections to reach the bench.

No Change in Two Decades

Our analysis suggests that people of color are underrepresented every step of the way. Although people of color are over 39 percent of the overall population of the United States, they made up some 12 percent of state supreme court candidates in 2017-18. Remarkably, this is the same percentage of candidates who were people of color in 2001-02, nearly two decades earlier.

Minority candidates also win at lower rates than white candidates. Only 15 percent of non-incumbent candidates of color have won open seat races, compared with just over a third of white candidates. Similarly, 3.4 percent of challengers who are people of color have won, compared with just over 14.3 percent of white challengers.

When minority candidates do reach the bench, as incumbents they also lose more frequently than their white counterparts. Minority incumbents have won 81 percent of their contestable elections, compared with a 90 percent success rate for white incumbents.

The headwinds for women of color are particularly strong. From 2000 to 2016, only 3 percent of the 589 challengers or open seat candidates for whom we were able to identify race and gender were women of color – 20 candidates in total. All 20 lost.

The First Hurdle: Money

The reasons for these disparities are complex. For example, we know that many minority candidates face obstacles to accumulating sufficient war chests – and that the pressure to fundraise can dissuade candidates from throwing their hats into the ring in the first place. Notably, our analysis found that while people of color running for state high courts are more likely to have prior judicial experience than white candidates, on average they raise fewer funds for their campaigns.

Supreme court races have also seen their share of racial dog whistle ads and racial bias among voters, while studies have found that in some states having a last name with a strong ethnic association can give judicial candidates a leg up – or down. An Asian judge in Illinois, Sandra Otaka, recounted, for example, that she was advised to add an apostrophe after the O in her name to give herself a better chance at winning in a state where Irish surnames overperform.

At the same time, it’s also clear that states can reduce hurdles for candidates of color. Evidence suggests, for example, that public financing reduces barriers to entry to the political process, making it easier for people of color to compete. Voters are also more likely to turn to racial or ethnic stereotypes when they lack other information about candidates -- highlighting the importance of voter guides and judicial performance evaluations for these typically low-information races.

Why were Anita Earls and Melody Stewart exceptions to these broader trends? Earls, a prominent civil rights attorney, was not a typical candidate in many ways. She was able to attract major financial backing, raising over three times as much money as her incumbent opponent, and benefiting from over $700,000 of advertisements from an outside group. A series of changes to judicial selection in the state by the Republican-controlled legislature – intended to benefit their own party – also backfired, most notably a decision to cancel judicial primaries, which resulted in two Republican candidates squaring off in the general election.

And both Earls and Stewart benefited from running as Democrats when localities across the country saw a blue wave. Yet while Earls and Stewart won their races, only five women of color challenged for a supreme court seat this year – and the other three candidates lost their races. It shouldn’t take a perfect storm of candidates and conditions to achieve a more representative bench. And we shouldn’t need to wait another 18 years for the next woman of color to win a high court election as a non-incumbent.

Alicia Bannon is deputy director of the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law. Laila Robbins is a researcher in the same program.