As China’s economic and diplomatic influence in Asia grows—and America redoubles its efforts to maintain a high profile in the Pacific—tensions between the two giant nations are simmering over a number of issues, from currency exchange rates to Burma to Taiwan.

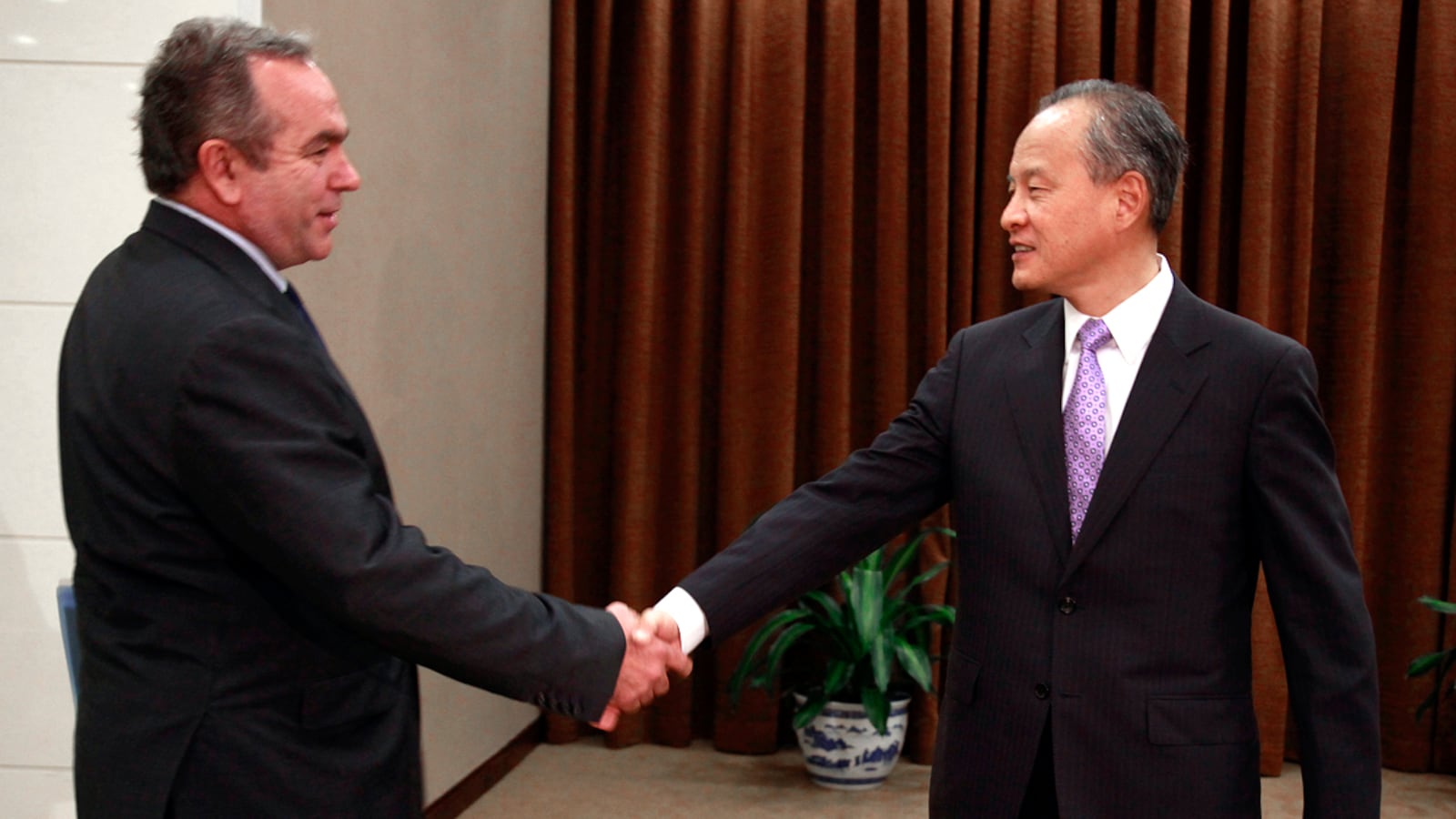

These strains were apparent during U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Asia Kurt Campbell’s visit to Beijing this week, capping off the diplomat’s tour of East Asia that aimed to emphasize America’s sway in the region. On Monday, China’s Vice Foreign Minister Cui Tiankai held a press conference to warn of a potential “trade war” and a “lose-lose” situation between the two superpowers if Washington decides to penalize Beijing for allegedly manipulating its currency. The Chinese media was even more disparaging of the U.S. Headlines claimed that “greedy Wall Street is the root of the financial crisis,” exhorted America to “cure its addiction to debt,” and alleged that the U.S. is trying to co-opt the hearts and minds of China’s neighbors through social media.

The most fraught bilateral issue continues to be China’s currency, the yuan. American legislators are considering a bill, passed by the Senate yesterday and now awaiting a decision in the House of Representatives, that would allow the U.S. to slap duties on imports from countries with undervalued currencies. The bill is a gauge of growing American frustration: the bill’s backers argue that the yuan, which they say is undervalued by more than 25 percent, needs to strengthen in order to rebalance bilateral trade and bring jobs back to the U.S. The bill’s critics say a stronger yuan won’t fundamentally resolve trade imbalances nor combat U.S. joblessness, and is mere political pandering by lawmakers hoping to look tough on China before 2012 elections.

The currency debate is just one of a number of disagreements between Beijing and Washington that have dogged Campbell’s Asian itinerary. Other red-hot topics include human-rights abuses in Tibetan communities, where Buddhist monks have immolated themselves in acts of desperate protest; the South China Sea dispute—in which the U.S. has enlisted Japanese and Indian support—where a half-dozen governments are contesting China’s claims on maritime territory; and U.S. arms sales to Taiwan. Last month, the Obama administration announced that it would sell $5.8 billion in arms to Taiwan, mostly upgrades for the island’s aging F-16 fighter jets. The decision provoked an expression of “stern opposition” from Cui.

Many vocal Chinese nationalists, as well as the country’s influential military brass, would have liked Beijing to show even more spine vis-à-vis U.S. arms sales to Taiwan. This bloc is likely to be similarly jittery about intriguing developments in Burma. Speaking at a forum in Bangkok on U.S. engagement in the Pacific, Campbell noted hints of a political shift in the secretive Southeast Asian nation. The Burmese regime, which traditionally has seen China as its Big Brother, recently eased censorship of the Internet and mainstream media, promised a mass release of prisoners (expected to include dissidents), and embarked upon what Campbell called a “very consequential” dialogue with opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who was released from house arrest in 2010. Campbell said there were “clearly changes afoot” inside Burma, and promised Washington would be ready to “match the steps that have been taken by the regime.” U.S. officials have already shown a greater willingness to talk with their Burmese counterparts. One reason for this warming trend is the possibility, at least in American eyes, that Burma may be seeking to reduce its traditional dependence on China.

China is Burma’s key foreign patron and biggest lender, and has massive infrastructure investments inside the country. But the lopsided relationship has also triggered fears inside Burma that the Chinese are looting the country’s rich minerals, natural gas, and other resources. In September, the Burmese government suspended construction of a $3.6 billion Chinese-backed hydroelectric dam on the Irrawaddy River that would have supplied power to China. The project had met with stiff grassroots opposition inside the country, triggering rare street protests in Rangoon. Burma’s foreign minister visited Beijing on Monday to try to resolve the disagreement, but Chinese authorities remain queasy about the possibility of competing with U.S. officials over Burma. “Of course, China’s strategic suspicions about U.S.-Burma relations will increase,” predicts Professor Shi Yinhong, a foreign affairs expert at Renmin University. “This diplomatic competition is something very tricky, and it cannot be brought into the open. Naturally there will be a lot of suspicion.”

At the root of many individual Sino-U.S. disagreements such as Burma is a big-picture disconnect in perceptions. “There is a misunderstanding between China and the United States on how to interpret the meaning of the Asia-Pacific region,” says international affairs analyst Sun Zhe of Tsinghua University. “The Pacific region is far bigger, according to the American interpretation; it includes Hawaii, and the U.S. is [therefore] one of the countries of the region. But China has a different interpretation; it thinks the region means Northeast Asia, the Taiwan region, the South China Sea and Vietnam—but not Hawaii. So the concepts are different.” With such vastly different views of the region and its shifting alliances, Campbell and his colleagues have a delicate mission ahead.