Four years ago, a North American Aerospace Defense Command officer sang the praises of a joint counter-terrorism exercise with Russian forces, named Vigilant Eagle.

“This exercise is one milestone in working together. Our folks are proud to be a part of such an important event and are passionate about partaking in efforts to protect our borders,” 176th Air Control Squadron operations officer Lt. Col. John Oberst said.

It seemed like a good idea at the time, but the lessons learned from Vigilant Eagle likely aided in the execution of a more recent exercise, its name unknown.

Russian Mikoyan MiG-31 Foxhound long-range fighters—a type that Russian forces flew in Vigilant Eagle—accompanied two Tupolev Tu-95MS bombers to a point 55 nautical miles from the Alaskan coast on Sept. 17. Two Ilyushin Il-78 air refueling tankers supported the formation, which turned back when it was intercepted by a pair of Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor stealth fighters.

In short, it had all the makings of a nuclear attack drill, part of an escalation in long-range Russian operations worldwide.

The flights showed a developing tactic, in which MiG-31s escorted Tu-95s and Tu-142s, the maritime reconnaissance version of the same Cold War design.

The change follows the introduction into Russian service of the modernized MiG-31BM, an upgraded model of a Cold War design that is now expected to be flying until 2029.

Also entering service is the Tu-95MSM, an improved bomber armed with the new Kh-101/102 cruise missile—a stealthy weapon with a reported range of up to 2,700 nautical miles In other words, all the aircraft and munitions Russia might need for a new Cold War.

This weapon mix offers the attacker new tactical options—including a reconnaissance-strike complex with the MiGs as shooters—and pose corresponding challenges for the defender.

Along with Russia’s persistence in the development of the Bulava sea-launched ballistic missile, the replacement of older intercontinental ballistic missiles by the road-mobile RS-26, and the apparent breach of the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces treaty by the testing of the Iskander-K truck-mobile cruise missile, these developments have (to put it mildly) weakened the argument that if the U.S. led the way in cutting its nuclear forces, the rest of the world would follow.

A U.S. administration that started out showing sympathy with the Global Zero movement—the one to eventually eliminate all nuclear weapons—has quietly taken decisions that point in a very different direction. Notably, the future of the nuclear-deterrence triad seems more assured than it has for many years.

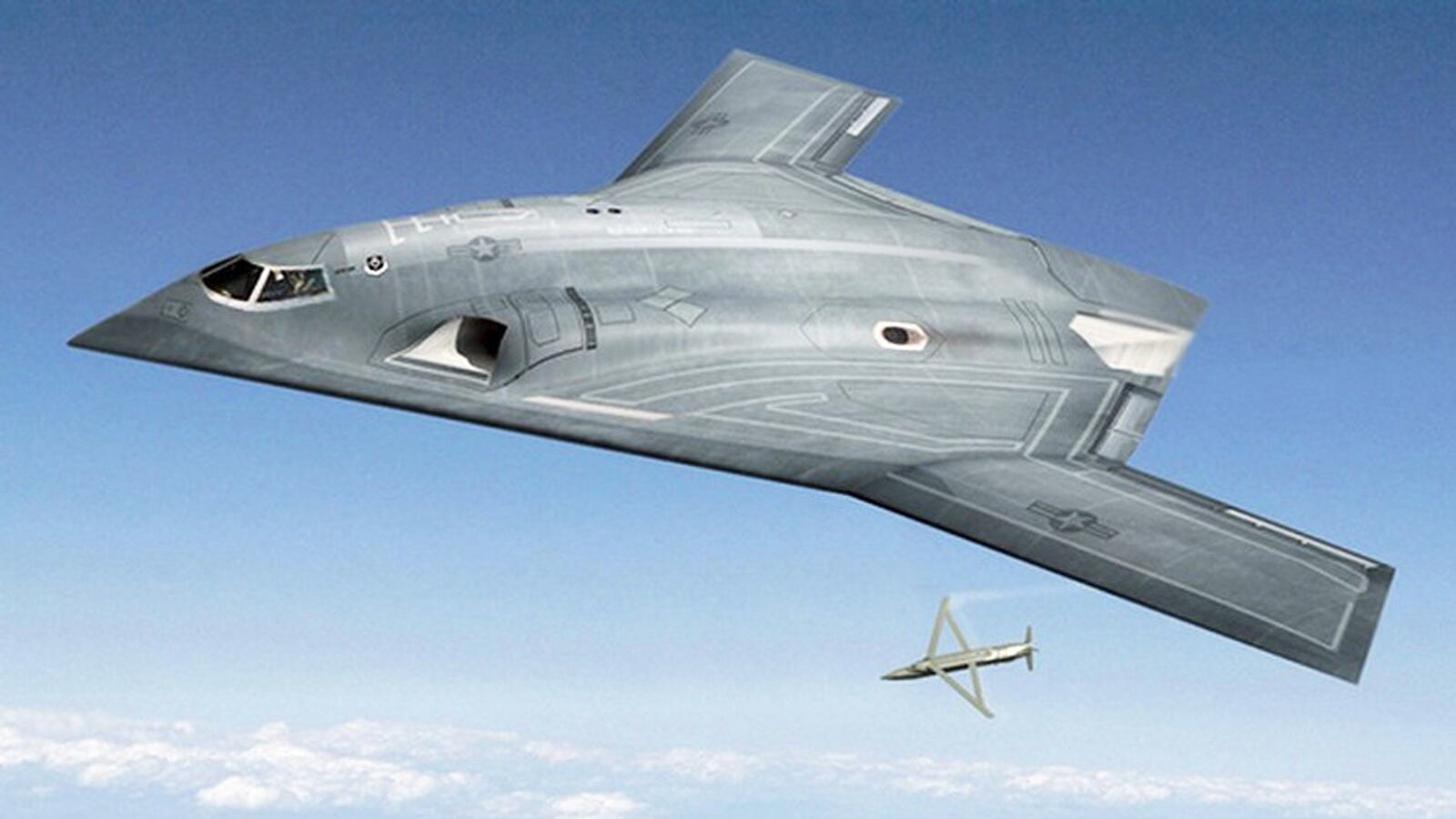

Between Obama’s election and inauguration, the first significant contract for what is now the Ohio Replacement Program submarine project was signed, and the administration has continued to support it. The controversial issue of whether, when and how the Long-Range Strike Bomber would be nuclear-capable has been put to bed: Every LRS-B will be nuclear-capable and it will be nuclear-certified two years after it enters service.

The LRS Family of Systems definitively includes a new cruise missile, and at a symposium in Washington this month, Lt. Gen. Stephen Wilson, commander of U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command, stated that the nuclear-tipped version will take priority over a conventionally armed missile.

The new submarine and the LRS-B are “uploadable” systems that can carry more warheads if strategic requirements change. A senior air force official last week said that the LRS-B would be designed with hardpoints—suggesting that it could be a cruise-missile carrier as well.

Also recently revealed is a plan for a new ICBM to replace the Minuteman III, the first such weapon since the short-lived Peacekeeper. Many analysts had expected the Minuteman to soldier on like Washington’s hatchet, with every piece being replaced from time to time, if the land-based ICBM survived at all. Now, the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent missile, sharing technology with the Navy’s Trident, will replace the Minuteman in existing silos after 2030.

But these plans are fiscally and politically difficult. The nuclear establishment is returning from a very long procurement holiday and finding what you usually find: leaky faucets, blown fuses, weed-ridden yards and a pile of bills.

The Ohio submarine replacement will eat one-third of the U.S. Navy’s shipbuilding budget (strained by the well-above-expectations cost of Ford-class carriers and Littoral Combat Ships) and the service is publicly calling for “top-line relief”—the technical term for “some of the Air Force or Army’s money.” Quietly, the Air Force is asking for the same.

While it now seems accepted that the National Nuclear Security Administration can do a Washington-hatchet trick on the nuclear stockpile, rather than developing the all-new warhead that hawks called for a few years ago, its infrastructure is heavy with Cold War and even World War II hardware; not only will this not last forever, but it is not an environment that attracts the best talent.

But the longest holiday of all has been philosophical: Most people, even in the armed forces, have been able to spend a long time not thinking about deterrence, and the world in which such matters are discussed remains small and somewhat isolated. As the world moves into an era of multiple, sometimes-unstable nuclear players and as the bills come due, that is a luxury we can’t afford.