On 23 June 2008, Robert F. Godec—then the U.S. ambassador to Tunisia—sent a classified cable back to the State Department on the corruption among the country’s ruling class.

“Whether it's cash, services, land, property, or yes, even your yacht, President Ben Ali's family is rumored to covet it and reportedly gets what it wants,” he wrote. “With those at the top believed to be the worst offenders, and likely to remain in power, there are no checks in the system.”

In December 2010 WikiLeaks published that cable, alongside dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of others covering events across the world—an act it did in partnership with The New York Times, The Guardian, Der Spiegel, Le Monde and El Pais.

The decision to publish the classified cables provoked a furious reaction from the State Department—but was also credited with helping to spark revolution first in Tunisia and then across the Middle East in the Arab Spring, by showing what U.S. diplomats already knew about the corrupt activities of dictators across the region.

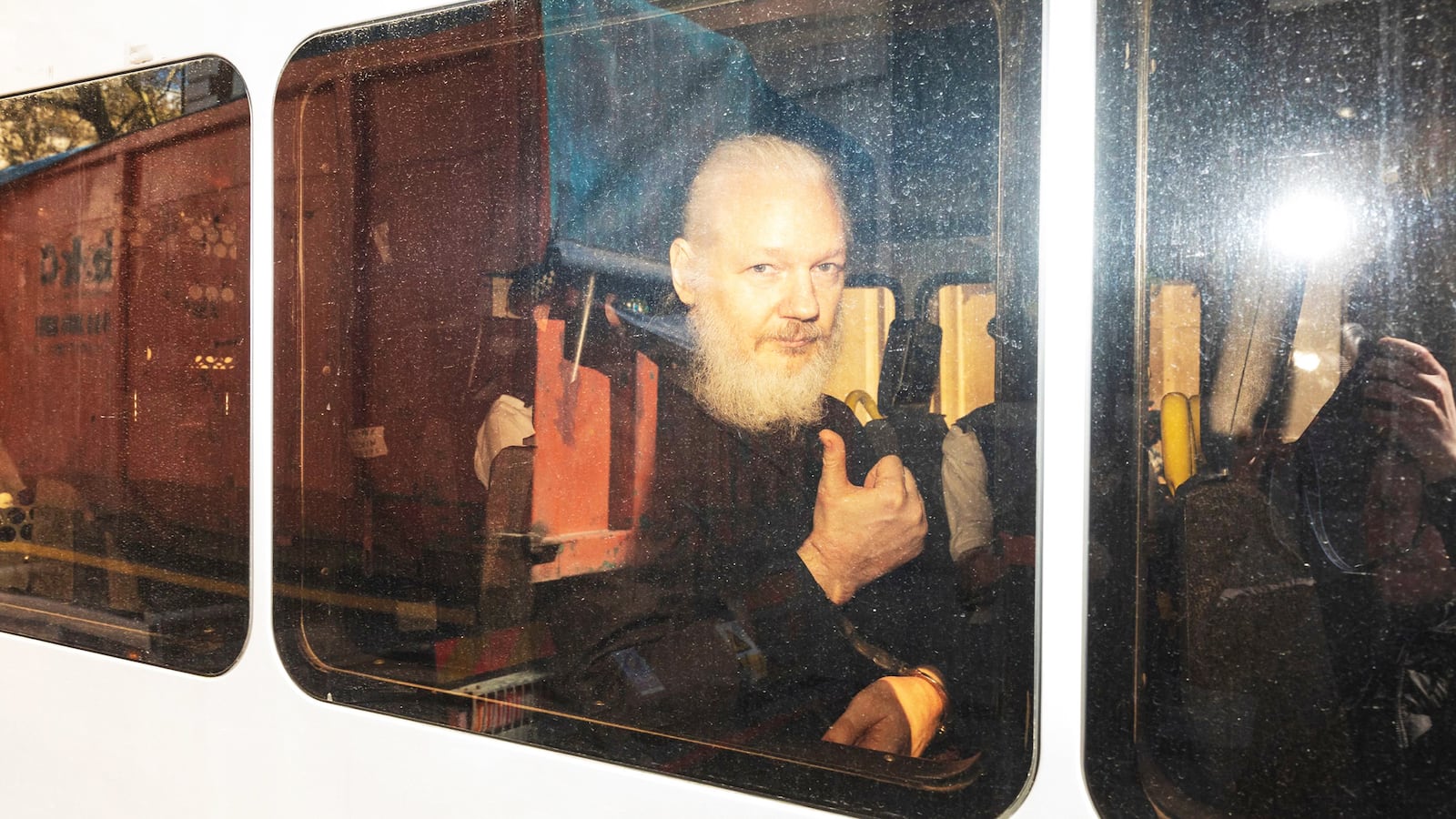

Now, more than eight years later, the U.S. has charged Julian Assange—but none of the other media outlets—under the Espionage Act for publishing those cables, and other material leaked to the site by the former U.S. army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning.

Doing this is not just an unprecedented threat to U.S. media freedom, it is also arguably a bid to punish Assange for the last good thing he did.

The material across Manning’s multiple leaks set light on wartime atrocities, on the corrupt act of dictators, and on what was going on behind closed doors in Guantanamo Bay. It was public interest journalism, supported by some of the most senior and respected editors in the journalism business. And it is being criminalized.

It is easy to forget the facts disclosed in 2010 by WikiLeaks amid the site’s own dramas and amid discussions of the size and scope of the leaks themselves. But they are many and significant—and shaped the news agenda over the course of a full year, across the world.

The first of the Manning releases was the video WikiLeaks titled “Classified Murder,” showing first the gunning-down of a group of suspected militants alongside a Reuters camera crew, and then further gunning of the people who came to try to rescue them. The casual attitude of the helicopter’s crew as they fired shocked and stunned the world, and first brought WikiLeaks to fame.

Months later, WikiLeaks and three newspapers published around 80,000 documents out of Afghanistan, as the Afghan War Diary, which shed light among other things on Task Force 373, an elite unit tasked to “deactivate” senior Taliban leaders—usually by killing them. The records showed the unit had been involved in the killings of, as CNN reported, “civilians, Afghan police officers and, in one particularly bloody raid, seven children while they attended school”—all without public debate or scrutiny, before the cables were published.

A similar, but much larger, cache of documents from Iraq detailed how more than 109,000 civilians had lost their life in the course of the U.S. invasion of the country and the bitter civil war it spawned, including often through tragic misunderstandings—euphemistically entitled “escalations of force”—at checkpoints, where civilians, often including children, were shot as they approached the roadblocks.

The final documents from Manning’s leaked cache were the inmate files of those detained at the Guantanamo Bay base in Cuba, who had been described as being “the worst of the worst.” In reality, the documents showed taxi drivers, Afghans working for the US, and even a doubly-incontinent 89-year-old man with severe dementia had been taken to the base.

The documents showed how wearing a Casio F-91W watch—one of the most common watches in the world—was taken as evidence of al Qaeda membership, which could get someone shipped to Guantanamo. They also showed the huge toll the base took on both the physical and mental health of those shipped there without trial.

These truths revealed by the leaked material are clearly in the public interest, and were republished across the world—and some were used as the basis for legal challenges and cases in courts across the world. Publishing them was the right decision, but it is this act in particular which Assange is facing prosecution for—an act which can only be seen as dangerous and politicised.

It is true that WikiLeaks does not make itself easy to defend. One painful issue for defenders of the site is the way the leaked material was published and redacted. Efforts were made to redact the Afghan war logs, by withholding around 7,000 of the cables in the most sensitive category, with an intention to manually redact names of people at-risk later.

Despite this, names and sometimes addresses of Afghans who had passed information to U.S. soldiers were missed in this process and were published, putting them at risk. The Iraq documents were initially redacted far more thoroughly—no one ever found a name as they were published—and the State Department cables were published incrementally, with names redacted.

After falling out with its publishing partners, though, WikiLeaks thought differently of this, and published the entire cache without redaction—with documents which included details of opposition activists in dictatorships, victims of child sexual abuse, and those working on anti-corruption efforts.

This was a reckless and irresponsible act, rightly condemned at the time by the five newspapers which had previously published alongside WikiLeaks. It did put vulnerable people at risk. But even years later, during the prosecution of Chelsea Manning, the U.S. Department of Defense acknowledged it had no evidence of anyone being harmed or killed as a result of the leak.

This doesn’t excuse WikiLeaks’ irresponsibility, but we shouldn’t let the imagined blood of the leaks obscure the real bloodshed revealed by the documents themselves.

Nor should we let WikiLeaks’ or Assange’s other actions mask the outrage of him being prosecuted for publishing the material they put out in 2010 and 2011. Assange is once again facing potential extradition to Sweden to face justice over an alleged rape in that country, having escaped potential sexual assault charges through waiting out the statute of limitations by taking refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy.

That is not a matter of press freedom, or a matter related to WikiLeaks: if this extradition is sought, there is no moral reason to oppose it.

Similarly, WikiLeaks has made numerous dubious decisions in the years since publishing the Manning leaks. During the prosecution of members of the hacking group Lulzsec—who hacked The Sun newspaper, Westboro Baptist church, and Sony—showed Assange coordinating with hackers.

The Mueller Report and independent reporting shows the emails WikiLeaks published from the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton aide John Podesta were hacked by the Russian state and passed to the website, though no-one has demonstrated whether or not WikiLeaks was knowingly working with Russia.

However, these are not on the charge sheet for WikiLeaks. The acts of journalism it performed in 2010, however, are. And it’s on those acts we need to focus.

Assange may not be everyone’s idea of a journalist. He certainly isn’t everyone’s idea of a good man. And WikiLeaks might not be your idea of a news outlet. But the material Manning released shed light on issues of huge public interest, and would not have seen the light of day without Julian Assange.

Chelsea Manning, via WikiLeaks and then the world’s mainstream media, showed the world more than it had ever seen about the conduct of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and of U.S. diplomacy across the world.

She has served seven years in jail for that, and is once again in jail for refusing to testify to a grand jury investigating Assange. And now Assange himself faces nine charges—each with a maximum 10 years in jail—simply for publishing that information (he faces another nine relating to obtaining it).

It is dangerous, it is damaging, and it is unjust. And if the prosecution is successful, it certainly won’t end with Assange. Both principle and pragmatism require the media to stand up for the man many of them hate. Will they rise to the challenge?