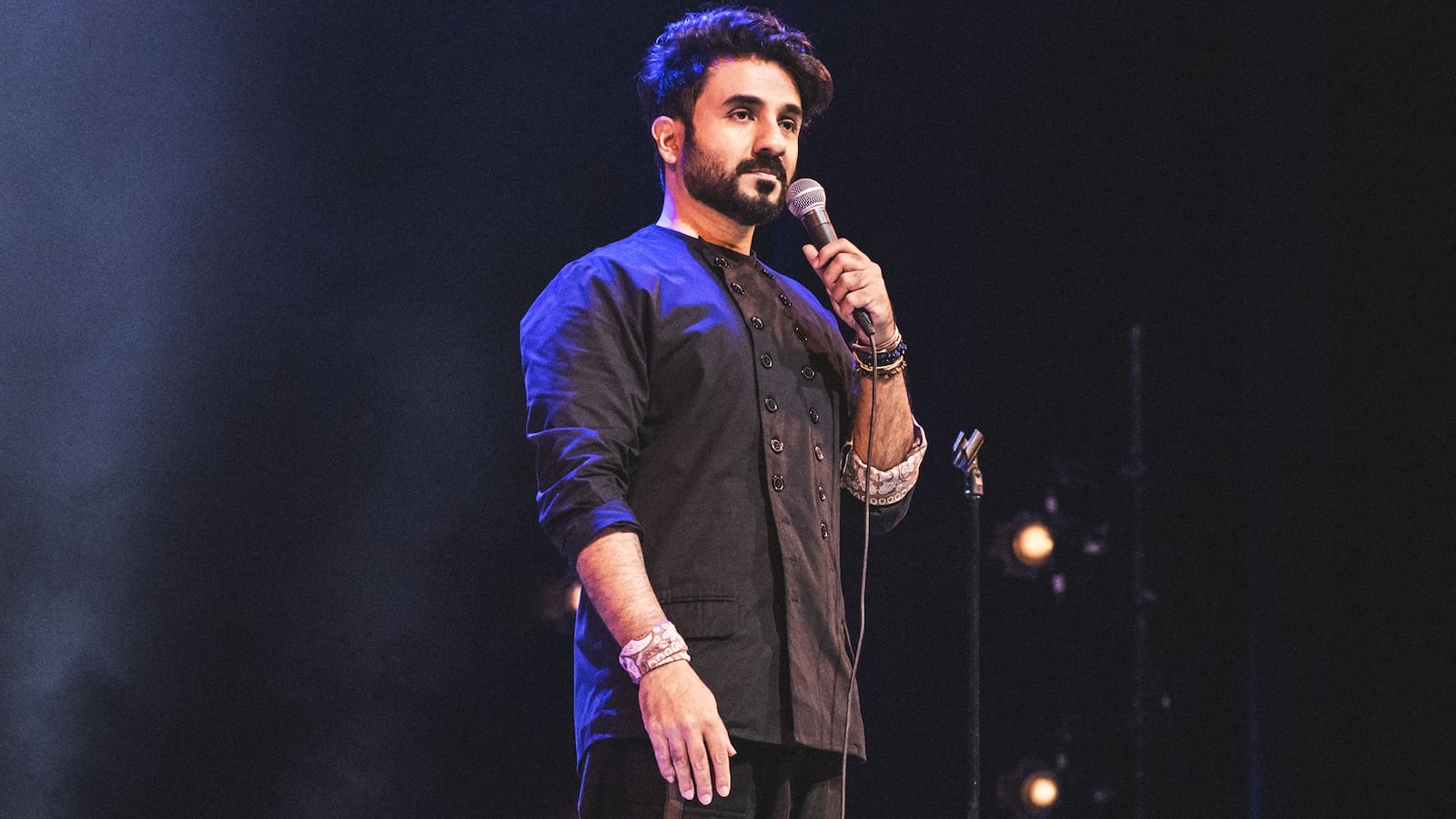

With five specials on Netflix and millions of followers on social media, Vir Das is an international comedy superstar who can sell out stadiums around the world. But his career nearly came crashing down after he put out his “Two Indias” video in 2021 and had charges brought against him for defaming his home country on foreign soil.

In this episode of The Last Laugh podcast, Das breaks down how he managed to turn one of the most painful experiences of his life into his strongest hour of stand-up yet in Landing, which premiered on Netflix this past December. He opens up about what it felt like to be labeled a “terrorist” for speaking out against injustice, shares how he pulled off the “magic trick” at the center of his special, and responds to American comedians who complain about getting “canceled” but have never been threatened with imprisonment for telling jokes.

On a November night in 2021, Das performed his full stand-up set at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and then returned to the stage to share a new piece he had written called “I Come From Two Indias.”

The five-and-a-half minute speech included lines that explicitly criticized his home country, such as, “I come from an India where children in masks hold hands with each other, and yet I come from an India where leaders hug each other without masks,” and even more pointedly, “I come from an India where we worship women during the day and gang-rape them at night.”

At one point, he even acknowledged the lack of jokes in his largely sincere speech by saying, “I come from an India that is going to watch this and say, ‘This isn’t stand-up comedy, where is the goddamn joke?’ And yet I come from an India that will watch this and know there is a gigantic joke—it just isn’t funny.”

“There’s a reason that you don’t see it in the special,” Das tells me of the video, “which is because the special is very much about the aftermath of dealing with outrage. And I think we live in a world where it’s reasonably unpredictable what’s going to and what’s not going to resonate with people or cause outrage.”

Das says he still doesn’t “quite understand” why the video “ended up getting a sea of love” and then “a sea of outrage as well.” It wasn’t until that outrage started to die down that he began to think about how he could “dig deep and turn the drama into something that brings people joy, which I think is essentially the job of a comedian.”

During that process, he asked himself, “Can I write a show that makes both the people who love and the people who are outraged laugh at the end of the day? And really, that’s what my show is about.”

It started, like most stand-up hours do, with one joke. “For two months, I agonized over that first joke,” Das says, explaining that he wanted it to achieve three things: make people laugh, make him the butt of the joke, and address the elephant in the room.

That first joke comes early in the new hour, when Das tells the audience what it was like to find himself on the homepage of the BBC website. “Big headline that said ‘Comedian Polarizes the Nation,’” he says in the bit. “Do you know how badly you have to fuck up before the British say that you divided India?”

“I think that encapsulates the whole thing, that there was polarization, I had messed up, and I was the butt of that joke,” he adds now. “I think I had to be the fool in it, and never in a way that victimizes you or lionizes you, but just sort of maintains you as an idiot throughout the entire process. I think that’s what people will relate to more than anything else, because they’ve been the idiot of their stories.”

Below is an edited excerpt from our conversation. You can listen to the whole thing by subscribing to The Last Laugh on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Stitcher, Amazon Music, or wherever you get your podcasts, and be the first to hear new episodes when they are released every Tuesday.

There’s a really beautiful thing that you do visually in this special with the divided stage that represents these two sides of yourself. How did you arrive at that idea and why did you want to execute it that way?

Because I have this sort of perpetual outsider perspective. I grew up in India, and then I was raised in Africa, and then I went to private school in India, and then I went to University in Delhi and public school in Delhi. Then I went to America. Then I went to Bollywood. Now I’m kind of all over the place. So I’ve always felt like this person who never belongs and is on the outside looking in. And then when I was writing this special, I’d seen a clip from The Prestige which is one of my favorite movies, and in The Prestige, Michael Caine says that there’s three parts to every magic trick: The Pledge, The Turn, and The Prestige. And it had been in my head that it would be really cool to structure a special around that, if there was a central magic trick at the center of the special. So what happens here is I “pledge,” I show you some sand. I pour some sand [on the stage] and I think you’re wondering what that is.

I had no idea why you were doing that in that moment.

We don’t talk about it until the end of the special. And then I keep cutting to random shots of shoes that, again, you don’t understand what they are. They’re very out of context and very jarring in the edit. And then, about 49 minutes into the special, we “turn” it. We reveal that half the stage is Indian soil and half the stage is American soil. And I’ve timed my footwork the entire time, where literally, in the entire special, every time I’ve done a joke about America I’m standing on “American soil” and every time I’ve done a joke about India, I’m standing on “Indian soil.” And then the “prestige,” which is that there’s a tagline to the special that is “the floor is home,” and you find me on the floor at the end.

It’s very clever as well, because it compels the viewer to go back and watch it again to track your footsteps—

And to see if they can catch me! Yeah, absolutely.

The narrative of the special leads up to the landing of your plane in India after your speech went viral. What did happen when you returned to India for the first time after all of this went down?

There was a ton of paparazzi. We turned our phones off. The theme of the special is you turn your phone on after two months and you discover that that hate is yelled and love is felt. And you find love. You’re thankful that the people around you gave you the stamina to stick around and wait for the love. If you ever find yourself at the receiving end of outrage or anger, hang in there, love is on the way. So I think that’s really what happened: We came back home, we went underground, we turned our phones off, turned them on two months later, and a sea of love found us. I swore to myself that if I ever was able to gig publicly again, I would make everybody laugh and really treat it as a privilege. And so then we announced a tour and I wrote that one joke. I was like, OK, I need more than one joke, and then we were able to tour the entire world with it. So I’m happy to say that something that begins with a little bit of drama is then pivoted to making millions of people laugh. I'm proud of that.

Was there a moment, though, that you felt like it might all be over or that you wouldn’t be able to do that anymore? And how did you deal with that?

Of course, yeah. I felt like I had let people down. I felt guilty. I never want to hurt anyone, and so I just felt guilty. External factors aside, all you can do is internalize it and say, what can I do personally? So I was just like, I hope personally, I can bring people to the table again.

What were the more lasting ramifications, if any, on your career and how you think about what you say on stage? Has it changed you at all, this experience?

No, I think that the audience will tell me where the line is. I still have to write the joke. That’s my policy. And the audience will let you know. They’ll slap you around if they need to slap you around, and they will cheer you on if they need to cheer you on. But don’t think about the line. Let them show you where the line is. And also, I had never really put myself out there in a special before, like really put myself out there, because I’m a little bit early in comedy to be comfortable with the silence and I don’t feel like I have the gravitas yet to really hold an uncomfortable moment. So on this special I had a rule for myself, which is that an uncomfortable silence will never cross more than 11 seconds. And there had better be a big goddamn laugh around the corner. But I’m glad I did because there’s more of a connection with the audience. I feel like the next time they see me or I see them, maybe we can take some more liberties with each other. And now we know each other a little bit. So I’m looking forward to seeing what that is. I had never put myself out there emotionally in a special before.

I feel like all of this relates to the broader conversation about free speech in comedy, cancel culture, and these issues that American comedians have been speaking a lot about over the last several years. You have a great line in the special where you say, “Please don’t cancel me, it will interfere with my incarceration.” It really highlights the stakes of what you are dealing with, speaking out about issues in India—there are much bigger stakes and consequences to that than the idea of getting “canceled” in the States.

Any day that you get to talk about your problems to a group of strangers on a stage or on Netflix is a pretty good day. Let’s be honest about that. I don’t think of myself as a comedian relative to American comedians or relative to anyone else. I don’t think comedians do ourselves any favors by talking about what’s fair and what’s unfair. If it’s fair, is it funny? And if it’s unfair, is it funny? And is it a story you want to tell? I think those are the questions that a comedian should ask themselves, if you’re looking to up your game, which I am.

And when you hear American comedians complain that they “can’t say anything anymore,” or they’re going to get in trouble, how do you react to that? Because it is just so different from what you have dealt with.

That’s something you feel, but I’d rather hear a joke about that than hear you say that. So if you feel like you can’t say anything, I’d love to hear a witty joke about how you feel like you can’t say anything, rather than you just vocalizing that. That’s my honest feedback.

Listen to the episode now and subscribe to The Last Laugh on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Stitcher, Amazon Music, or wherever you get your podcasts, and be the first to hear new episodes when they are released every Tuesday.