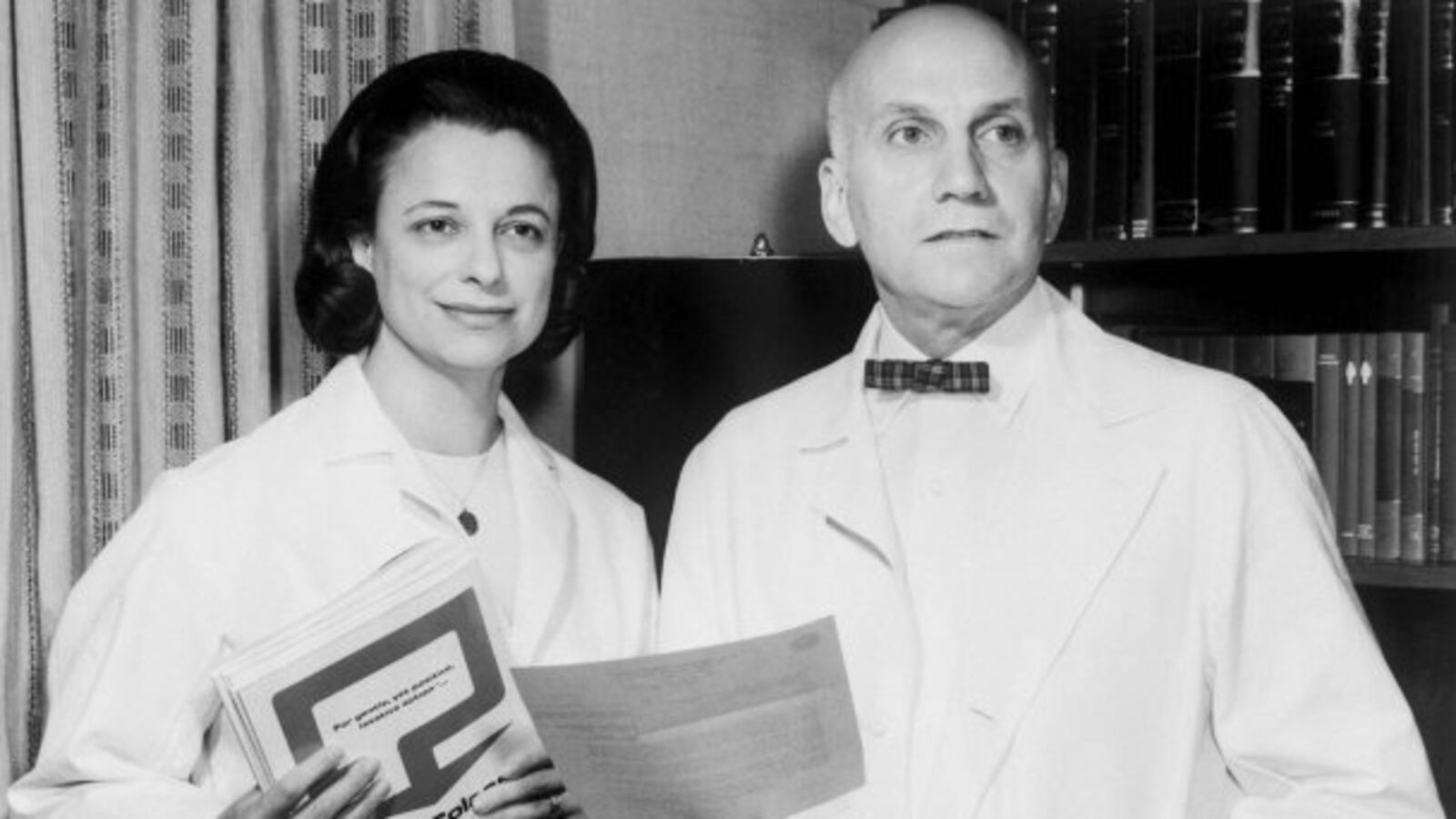

Who knew Virginia Johnson, a Missouri farm girl born during the Great Depression, would find her calling as a trailblazing sex researcher in the 1960s, watching couples fornicate and women pleasure themselves with vibrating dildos in lab rooms? As the clever partner of St. Louis gynecologist William H. Masters, she helped revolutionize the treatment of sexual dysfunction; debunk Freud’s theories that vaginal orgasms were superior to clitoral ones; and, perhaps most explosively, prove that women were capable of multiple orgasms.

Johnson died earlier this week at age 88, more than 50 years after she became the female half of the famed Masters and Johnson team whose groundbreaking research forever changed our understanding of human sexuality.

In 1957, Masters—a church-going doctor on staff at the Washington University School of Medicine—was seeking a female assistant to help with his surreptitious studies of the human body during sex. He settled on his newly hired secretary, 32-year-old Virginia (known as “Gini”), who was twice-divorced with two kids and ambitions to study sociology. Since Masters was particularly interested in female sexuality—and, like many men, “knew nothing at all about it,” as he later admitted—he sought her perspective as a sexually active, intelligent woman. (Johnson was experimental and upwardly mobile from an early age. She lost her virginity to a farm boy at 16; married a much older lawyer at 22; divorced him three years later to marry George Johnson, a musician; and finally divorced him, too.)

She had no proven aptitude for lab studies, but she was intuitive—something Masters needed in a female partner more than a degree. “Women in medicine at that time had enough traumas; I couldn't do that to them," Masters said in a 1994 interview with The New York Times, acknowledging that female MDs in the ‘50s were hardly respected in a male-dominated medical field. Sex research was out of the question for a woman with a professional or social reputation to uphold. Johnson had neither.

But she was an ardent apprentice with a natural bedside manner when it came to taking down patient histories or persuading people to literally drop their pants in the name of Masters’ seemingly dubious experiments. “Gini would go to every cafeteria at the University of Washington [sic] convincing all of the nurses and graduate students and faculty wives to be part of their study,” says Thomas Maier, author of Masters of Sex, an exhaustive biography on the duo. Female volunteers would come late at night to Washington University’s Maternity Hospital, where they were hooked up to machines that tracked electrical impulses in their brains and received an optical, dildo-shaped device to monitor different stages of arousal in the vagina. Masters and Johnson witnessed an estimated 14,000 orgasms over nearly a decade of research, the results of which were published in their landmark 1966 book, Human Sexual Response.

Meanwhile, the pioneering duo had been going at it themselves since the early days of working together. Their clandestine sexual relationship and sparks between the sheets further informed their studies. Love ostensibly took a backseat to chemistry, though other couples struggling with intimacy issues sought out their avant-garde sex therapy, which they detailed in their 1970 book, Human Sexual Inadequacy. They married a year after its release, but both would maintain that their partnership was fundamentally professional, not romantic. "We kind of belonged to other people, not ourselves," Johnson later told the Times. "We thought in terms of our work and what we hoped to accomplish, not a private or social life.”

By the time their pairing was sealed in marriage, they had already been established as equals, their names synonymous with the biggest brand of postwar sex research. The fact that Masters gave Johnson equal billing on his life’s work—something most male doctors at the time would never dream of doing—was a reflection of how much he admired and adored her. Masters had the degree, but it was Gini who, by sheer dint of her energy, intellect and charisma, was largely responsible for the success of their work. It was she who developed the formula for their therapy, which had an 80 percent success rate and became their primary moneymaker. Celebrities and public figures from actress Barbara Eden to Alabama Governor George Wallace went with their spouses to Masters and Johnson’s Institution seeking treatment for all kinds of sexual dysfunction, and the Institute’s program was later adopted by most sex-therapy clinics in the country. As Maier puts it, “Until Viagra came along with a solution in a bottle, they were the fastest cure to what ailed America’s bedroom.”

The country was shocked to learn of their divorce after 22 years of marriage. (Masters swiftly remarried a woman he had met 55 years earlier when he was a medical student.) But the split was amicable enough that they continued working together until the mid-90’s. "In two things we have common ground—the drive to do something extraordinary and an appreciation of the subject matter," Johnson told the Times. Indeed, their contributions to the science of sex over five decades of working together were invaluable, particularly their clinical discoveries of female anatomy and women’s untapped sexual power. More important, their findings are still relevant.

“They pinpointed that the biggest problems couples had with sex often stemmed from lack of information or education about it, and that remains true today,” says Debby Herbenick, a sex educator at The Kinsey Institute.

Masters may be remembered as the driving force behind their work, but his early scientific theories would never have been realized were it not for Johnson. In September, the two will be immortalized in Showtime’s Masters of Sex, based on Maier’s biography. Both the show and Johnson’s character, played by 31-year-old Lizzy Caplan, will likely resonate with female contemporaries. “Gini's view of sexuality is a lot like modern, younger women today who look at love and sex on their own terms—as equals with men,” says Maier.

Johnson once credited Masters with "creating" her, but it was she who brought a much-needed female touch to the field of sex research. Today, as Daniel Bergner detailed in his recent best-seller on female sexuality, What Do Women Want?, impassioned women like Johnson are once again leading their field to elucidate new truths about women's carnal desires, which—like the woman who brought them out from under the covers—are as beguiling as ever.