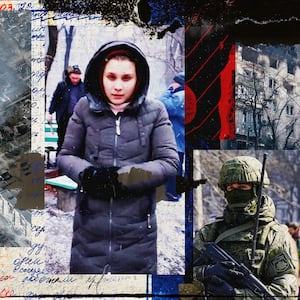

BORODYANKA, Ukraine—“I feel empty, like this photo,” Maria Litvin, a 26-year-old painter, told The Daily Beast as she held up a picture of two ruined buildings, one on each side of a pile of rubble that had been an apartment block less than six weeks ago.

She was standing in what was left of her bedroom in an apartment in Borodyanka, a small town around 40 miles from Kyiv that the Russians have razed to hell. The floor was covered in broken glass and smashed furniture. Had Litvin been in the room when bombs rained down March 1, the glass could have ripped her to shreds. Instead, when they heard the jets flying overhead, she, her mother, and grandmother hid in their cramped shower and bathroom and were spared.

But 27 people in their apartment complex were not so lucky and were killed in the blast. Many had been hiding in the basement of a building next door, which collapsed and buried them alive. Investigators believe there are still dozens of bodies underneath the rubble, and some may never be retrieved.

After Ukrainian forces pushed the Russians out of Kyiv Oblast on April 3, there was a brief period of jubilation. The Ukrainians had resisted the initial Russian offensive, and the survival of their nation and its capital seemed assured. But this relief quickly turned to horror and disgust as the full extent of the war crimes committed in the towns occupied by Russia became clear. In Bucha alone, at least 500 corpses have been found, many apparently the victims of summary execution. Local women and girls have reported repeated incidents of rape and sexual violence.

When The Daily Beast visited Bucha this week, authorities were exhuming a mass grave of nearly 60 residents in a plot of land next to a small church. A team of war crimes investigators was also present, inspecting the bodies for tell-tale markings of bindings around the neck and wrists that indicate execution-style killings.

Despite the utter horror in Bucha, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky has warned that the situation in Borodyanka could be even more dire.

Borodyanka is a classic “one-street town” of just over 10,000 people, which residents speak of without particular affection. Litvin said that like many young people, she had left as soon as she could to study in Kyiv, and now spends most of her time in Ivano-Frankivsk in western Ukraine. The buildings lining Borodyanka’s central avenue are drab gray Soviet-style high-rise apartment blocks and the only hint of art or sculpture in the town is a statue of Ukraine’s national poet, Taras Shevchenko. Even this expression of culture was too much for the occupiers, who allegedly smashed the head off the statue the day they arrived.

Now, Borodyanka is a hellscape of destruction. Dozens of orange-vested workers shovel rocks and concrete into heaps, while bulldozers patrol the streets digging for remains. In Bucha and Irpin, the main streets are already mostly cleaned up, and bridges and buildings are being assessed for reconstruction. Shortly down the road from Irpin, there is a graveyard holding dozens of burned-out wrecks of cars that have been towed and dumped in a clearing near a forest. The residents here cannot imagine the town ever being rebuilt, such is the scale of the destruction.

Borodyanka was directly on the road of the Russian advance to Kyiv, so Putin’s troops chose to flatten it with airstrikes to smooth their advance. At least a dozen residential apartment blocks were destroyed, along with dozens of smaller houses, shops and a supermarket.

One resident, a white-haired man in his sixties who did not wish to be named, showed us the remains of an apartment where his dead neighbors had recently been pulled from. They were a young couple with two children, all of whom had been killed instantly. “There was no military here, no Ukrainian army, just a few poorly armed territorial volunteers. There was no reason for this type of attack,” he said.

Tatiana, Litvin’s 50-year-old neighbor who only wanted to share her first name, said that after the initial airstrikes the humanitarian situation in the town quickly deteriorated. “My doctor—one of the last in the town—also died in that basement,” she said. After that, they packed their stuff and left for a refugee basement shelter close to the station of Borodyanka. They spent almost all their time there during the invasion.

“Russians were just shooting with tanks and guns at every building. They told us, ‘Borodyanka must be destroyed, it can no longer exist,’” Tatiana told The Daily Beast. She names them as the infamous “Kadyrovtsy,” the Chechen forces who are implicated in many of the worst atrocities in Bucha. “They even tried to make us believe that the Ukrainian army was defeated,” she added. Now that the Russians are gone, Tatiana is staying with her husband and her mother in a house nearby.

Russia, of course, dismisses all these allegations as “fake news,” claiming its soldiers have acted with the utmost restraint in the face of overwhelming evidence of their barbarity.

Ukrainians are bracing themselves for an even greater catalog of crimes to appear when they explore areas surrounding the nearby cities of Chernihiv and Sumy, which were also besieged by Russian forces who withdrew at the same time as those assaulting Kyiv. The Russian Foreign Ministry has already warned that Western intelligence has prepared further “provocations” in these regions—a sure sign that they are aware of what their troops have left behind and are prepared for more crimes to be uncovered.

For now, the residents of Borodyanka have created a makeshift memorial out of the possessions of the dead. It sits near a bomb crater left by the worst of the airstrikes, where an oversized child’s teddy bear with vacant white eyes stares out over the wreckage.