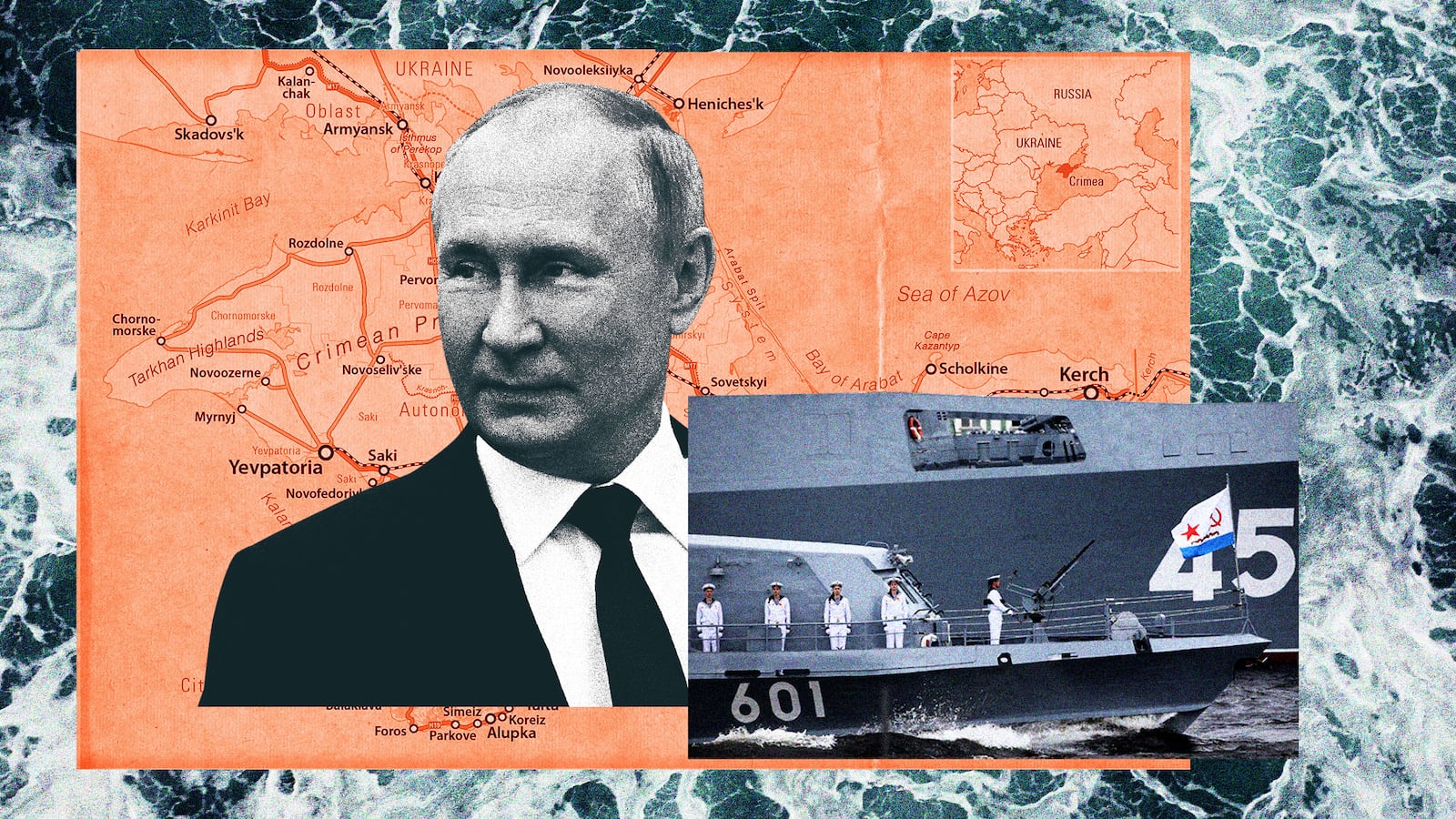

The Russian Navy is still sheltering in its base in Crimea after a sweeping Ukrainian drone attack last week.

On Oct. 29, Ukraine launched 16 air and naval drones at Russian ships in the bay of Sevastopol, causing damage to at least one ship and leading Russia to temporarily pull out of the lauded grain export deal in retaliation. According to a recent analysis by the U.S. Naval Institute, Russia’s fleet in the Black Sea has been timid since the attack, which is the latest in a series of setbacks since the invasion in February.

Russia’s Black Sea Fleet dwarfs the remnants of the Ukrainian Navy and should by all accounts be able to launch missiles and amphibious landings off Ukrainian shores with relative impunity. But for all their strength on paper, the Russian navy has gone from disaster to disaster since the start of the war.

In March, Ukraine hit a Russian landing ship in the port of Berdyansk with a ballistic missile, forcing the crew to scuttle the vessel. Ukrainian forces also sank the Russian flagship Moskva with two anti-ship missiles in mid-April. While not as spectacular as sinking a flagship, Ukrainian missiles and drones destroyed smaller Russian naval vessels throughout the conflict.

Russia has a large navy, but its losses in the Black Sea are difficult to replace.

Moscow cannot simply send more ships to the Black Sea, since Turkey controls the straits leading from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean and has the legal right to restrict access during wartime. Turkey’s refusal to let naval vessels through means that the vessels currently there are all Russia has in the short term, and is why the Oct. 29 drone attack was so detrimental. Ukraine was able to put a large number of explosive drones near Russia’s prized vessels, including one Kilo-class submarine. While it isn’t clear how much damage was inflicted, that any of the drones were able to penetrate Russian defenses makes it uncertain if Russia’s ships are truly safe when not in port.

That drone attack was the first time air and sea drones attacked simultaneously in this conflict, but both had been used in the area separately. Ukraine’s one-way attack drones, which have seen infrequent use since June against Russian military and oil facilities, targeted the Russian Black Sea Fleet headquarters in mid-August. In September, a previously unseen Ukrainian Unmanned Surface Vessel (USV) washed up on a Crimean beach. Using both at once was an attempt to overwhelm Russian defenses and complicate future efforts to defend Crimea.

USVs, even if they don’t end up doing much damage, are a tricky problem for navies to deal with. In the Red Sea, Saudi Arabia has struggled to prevent USVs operated by Houthi rebels from reaching their ports. The need to defend ships and ports from cheap USVs and other fast-attack craft is part of the reason the U.S. Navy has invested so heavily in directed energy weapons and why the U.K. procured Martlet missiles for its ships and helicopters.

To make matters worse for Russia, Ukraine’s Navy is slowly starting to grow again. Ukraine is receiving patrol boats from the United States and the Royal Navy is training Ukrainian sailors. The patrol boats are small and lightly armed, but they can still help Ukrainian naval and Special Operations forces along Ukraine’s rivers and coastline. Given Ukraine’s unexpected successes at sea, its partners are likely to continue and increase their support. And considering Russia’s struggles to adjust to new threats on land and sea, Moscow will struggle to cope with the growing threat of Ukraine’s missiles, drones, and new vessels.

Ukraine’s innovative use of missiles and drones to fight the Russian Navy has made it challenging for Russia to operate at sea. The strategy has helped Ukrainian soldiers and civilians on land while keeping the grain export deal alive. Without good options for preventing future attacks and an eroding grip on the Black Sea, the Russian Navy will likely stay cautious.

The U.S. Naval Institute analysis notes that Russia’s smaller patrol boats have recently been replaced by larger vessels more capable of stopping attacks, and some vessels have been moved from Sevastopol to Novorossiysk, which is further from the fighting.

The naval war is nowhere near won. Russia still has a much larger navy and can still launch missiles such as the Kalibr at Ukrainian cities from its vessels. Ukrainian missiles and drones might be able to seriously damage Russian ships, but sinking Russian ships will be difficult if Moscow decides to keep them out of range of Ukraine’s missiles at sea, and defended from drones when in port.

Still, for all Russia’s advantages, it’s unlikely that Putin and his admirals will find an easy answer to Ukraine’s strikes any time soon.