If there were a contest for the photographer, alive or dead, with the greatest reputation based on the smallest amount of work, Walker Evans would win in a walk. This is not, as you might imagine, a matter of culling out bad images and then weighing his worth based on what’s left. It’s simply that Evans didn’t take many pictures, unlike most photographers. He certainly didn’t publish a lot.

So it’s not at all strange to study just one image to see what it tells us about the man, his work, and his circumstances. Jerry L. Thompson does just that in The Story of a Photograph: Walker Evans, Ellie Mae Burroughs, and the Great Depression, published as a 63-page ebook by Now & Then Reader. Thompson, a photographer himself and one of Evans’ last assistants, looks long and hard at a portrait Evans made of an Alabama farm wife in August 1936, while working with the author James Agee on a story for Fortune magazine about farmers hurt by the Great Depression. Their collaboration ultimately yielded the unclassifiable classic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

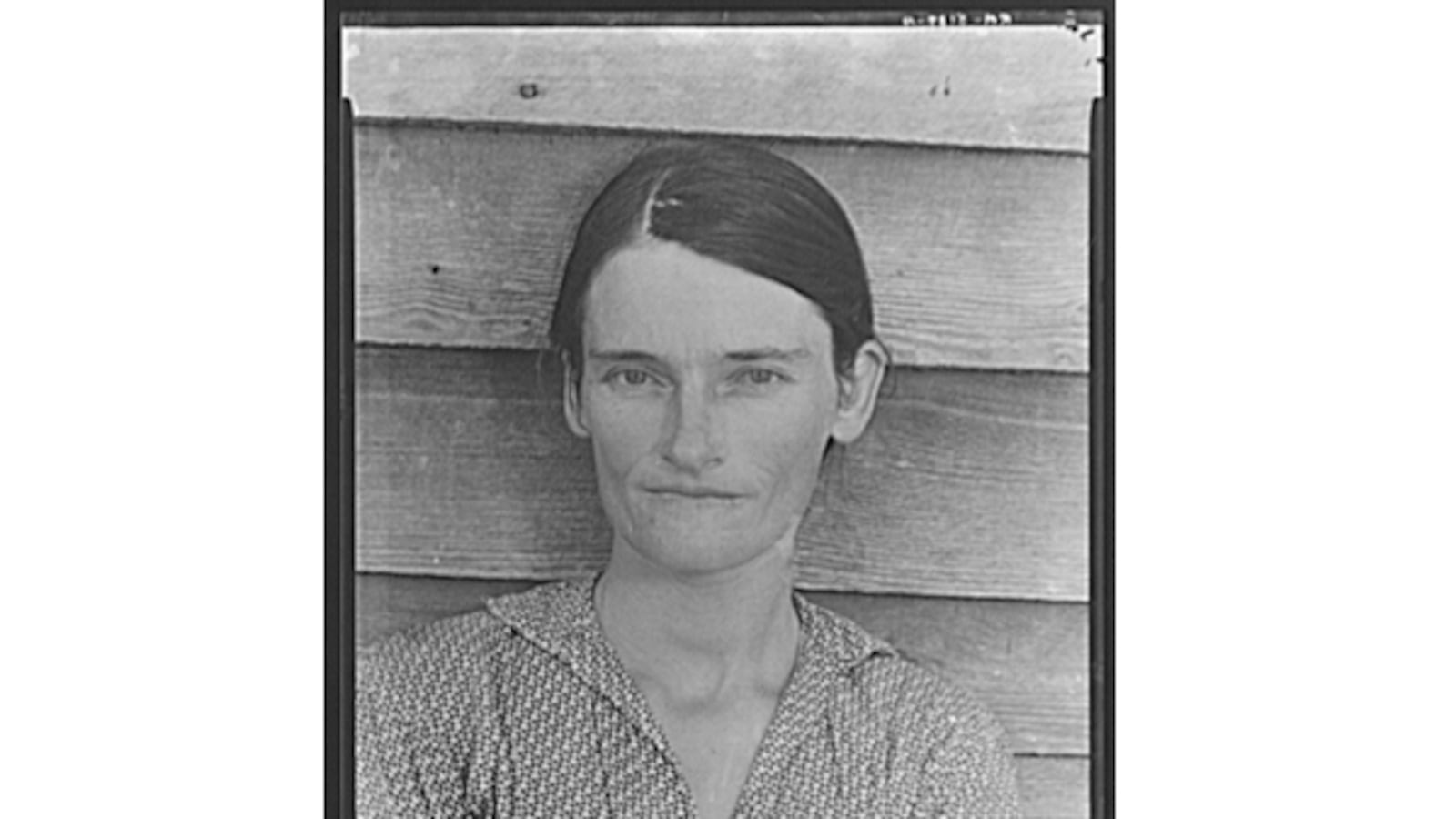

The black-and-white portrait of Mrs. Burroughs looks fairly straightforward at first glance: she stood in front of a clapboard wall, and Evans took her picture. But first glances rarely tell the whole story. After reading Thompson, you won’t ever look at this photograph—or maybe any photograph—in quite the same way.

Thompson begins with Evans’s declaration that he was not a documentary photographer but that he worked in a documentary style. It is not an empty distinction. A newspaper reporter covering a fire is a documentary photographer. Evans borrowed that just-the-fact-ma’am style in the service of art. Thompson points out that the Depression is history, and Ellie Mae Burroughs and Walker Evans are long dead. All that remains is the photograph, which can no longer influence anything or inform us about any immediate socio-economic conditions in the Deep South. Instead, it stands on its own merits as an image. “Perhaps part of what Evans meant,” Thompson says, “in making his careful distinction between documentary and documentary style, between document and art, between useful and useless was nothing more than this: art is long, but life is short.”

The best part of Thompson’s essay is his recreation of how Evans took the photograph. To do this, the author walks us through the manipulation of an 8 x 10 Deardorff camera, a big, clumsy thing on a tripod that is the very opposite of a hand-held camera that allows the user to stalk his subject with stealth and speed. An 8 x10 can yield images of astonishing depth and clarity, but a host of factors must align for things to work. By the time Evans climbed under the black cloth attached to his camera on that August day in 1936, he was a master technician. But the most interesting aspect of that encounter with Ellie Mae Burroughs, as Thompson emphasizes, are the things Evans could not control.

“He could control the darkness of the shadows collecting in Ellie Mae’s eye sockets and under her chin, but he could not control how she reacted to a large camera being placed so closely to her face. He could not control the pattern of lines beginning to etch themselves into the skin of that young face. He could not control, but only watch, the play of eye tension and mouth tension on that face as he waited for the right instant to click the shutter. And apparently he could not control the length of his close contact with her: he exposed only four sheets of film.” A few lines later, Thompson puts it more bluntly: “Evans took the pictures, but he didn’t make them by himself; he and Ellie Mae made them together, as a collaboration.”

Evans kept two subtly different images from that encounter. The photograph that found its way into the suite of pictures that opens Let Us Now Praise Famous Men shows a worried, quizzical woman. The other image, where she allows herself the ghost of a smile—paradoxically, it seems the sadder of the two pictures—Evans included in American Photographs, the seminal catalog of his 1938 one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art, the first such show ever granted a single photographer by that museum. One of the pictures is taken with flash, and one without. At the time, the technological requirements of using flash with the Deardorff would have meant that Evans had to move very quickly and surely to change strategies on the spur of the moment. The results are two photographs that are similar but different, and different enough to make both of them keepers. An artist may not know what he’s after, but he knows when he’s got it.

Evans has been criticized as a cold artist. More specifically, he has been accused of not caring about his subjects, that he objectified them with little humanity, that he would have been as happy photographing a turnip instead of a poor Alabama woman. Thompson demolishes this thesis with a quote from Lionel Trilling’s review of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: “Perhaps the most remarkable picture in this book (I think it is one of the finest objects of any art of our time) is the ... picture of Mrs. [Burroughs] … In this picture [the “sterner”] Mrs. [Burroughs], with all her misery and perhaps with a touch of pity for herself, simply refuses to be an object of your ‘social consciousness’: she refuses to an object at all—everything in the picture proclaims her to be all subject.”

Anyone interested in Evans, the art of photography or simply the act of looking closely at the things of this world and the people in it will benefit from this lucid examination of one artist and one of his greatest works.