Most mornings, I left our rented cottage, and walked into Southwold. The gravelled path that passed within meters of our front door wound along the edge of the Heath, until it reached the concrete platform where Walberswick station used to stand, where it turned sharp right and headed straight for the River Blyth. It was following the line of the old narrow-gauge railway that used to run from Halesworth to Southwold, and it crossed the river on a narrow metal bridge. There were boats beached on the mudflats on the sea-ward side, and inland, a single, sail-less windmill stood guard in the featureless marshes.

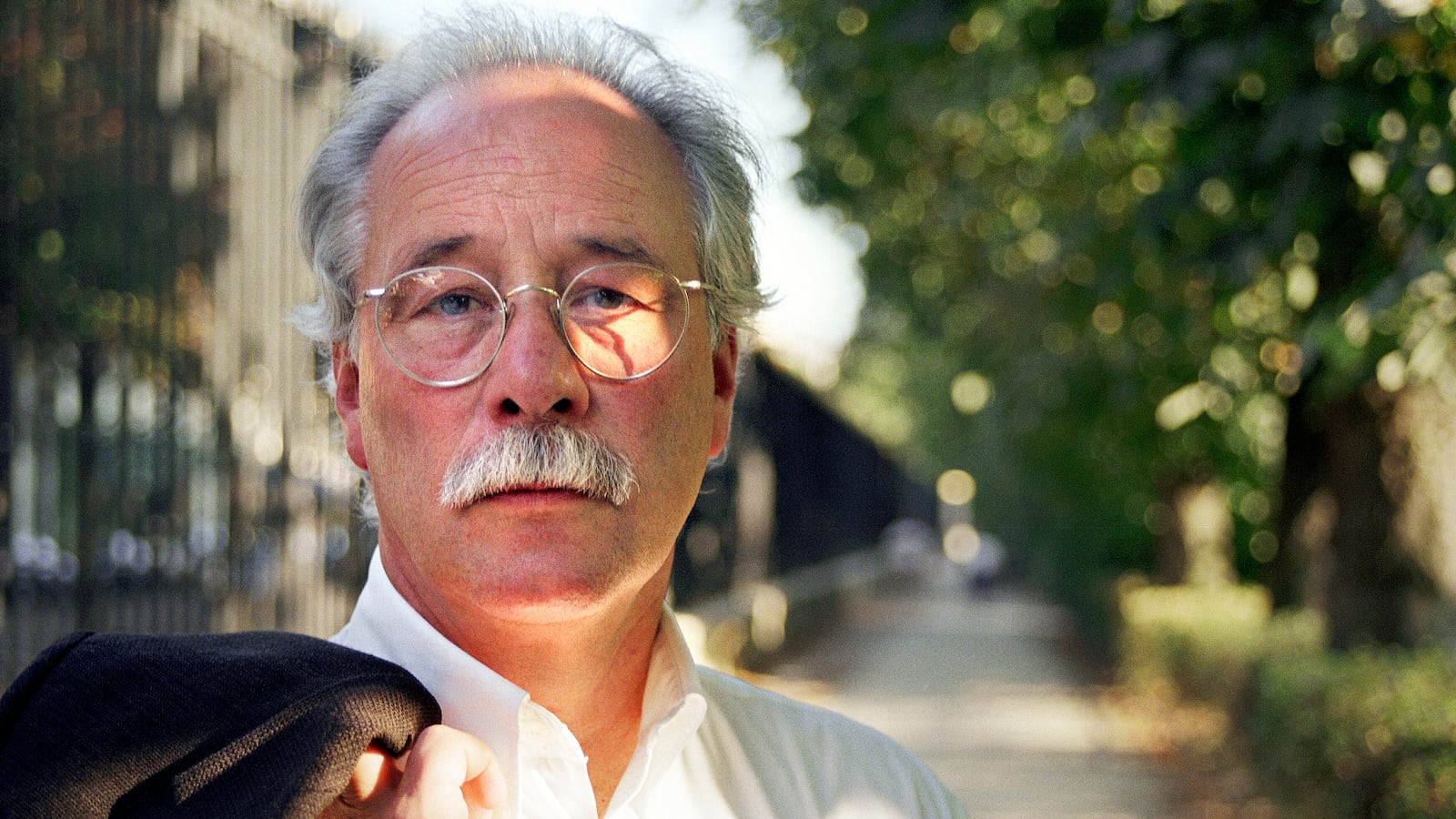

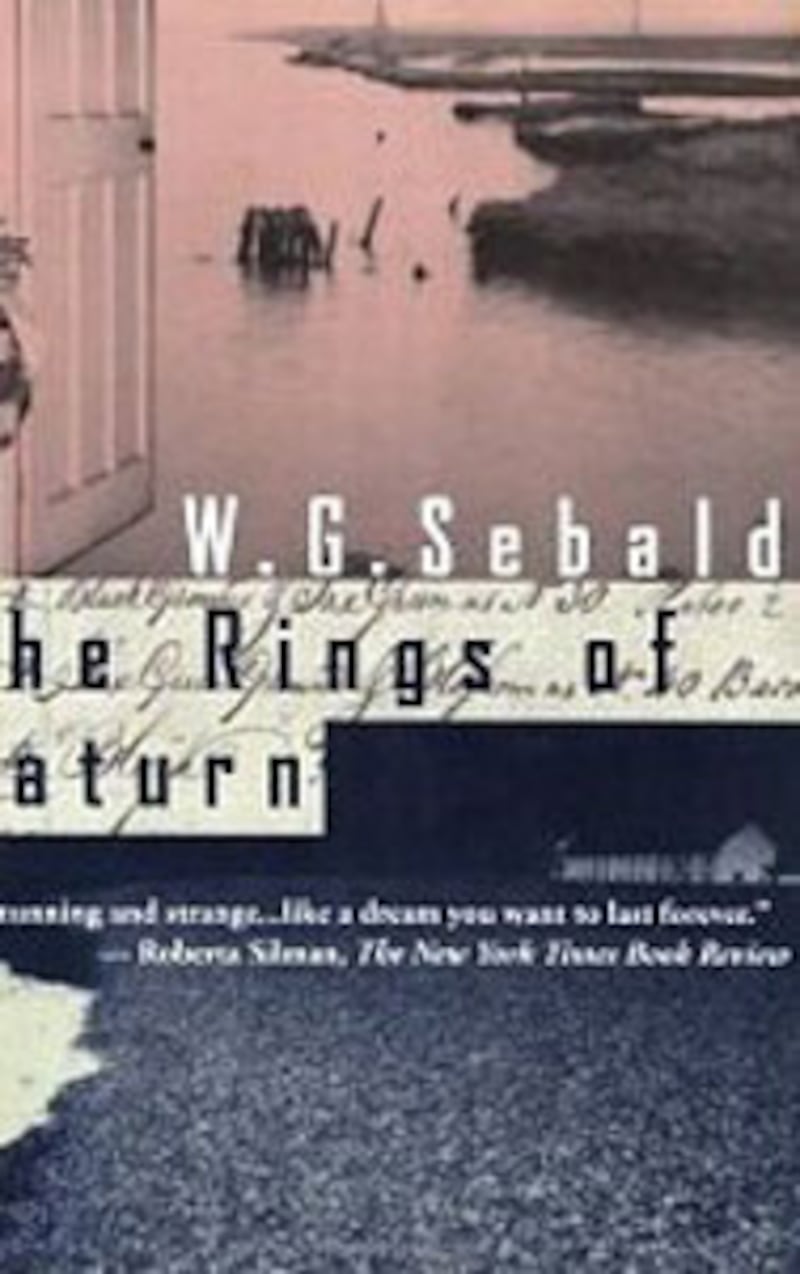

Whenever I crossed the bridge, I would think of the German writer W.G. Sebald, who had approached it from the opposite direction in the course of the walk that inspired his masterpiece, The Rings of Saturn. Sebald did not stop on the bridge for long, but it served as a point of embarkation for one of the far-ranging meditations that make up the substance of the book. He had discovered that the train that used to run on the railway had been built for a Chinese emperor, and he found himself carried back, as if by the tide that flowed beneath the bridge, to the events of the Taiping Rebellion and the tyrannical rule of the Dowager Empress Tz’u-hi in 19th-century China.

It is one of many moments when the narrative escapes the constraints of the Suffolk landscape, and plunges vertiginiously through time and space. It incorporates a vast range of subjects, such as the life and work of other writers, the inevitability of death and decay, and the human instinct for violence and destruction.

The Rings of Saturn appeared in English in 1998, only three years before Sebald’s death at the age of 57, and it confirmed a literary reputation that has continued to grow with the posthumous publication of four other books. The latest, A Place in the Country, is a collection of essays about writers and artists that inspired him: Whether or not it will be his last book remains to be seen, but according to one of his former colleagues at the University of East Anglia where he taught for 31 years, it is a conclusion of a sort. Jo Catling, who wrote the Introduction to A Place in the Country, says that its “loose structuring” around “an Alemannic region comprising south-west Germany and north-west Switzerland and Alsace” makes it “a kind of literary homecoming, after the ‘English pilgrimage’ of The Rings of Saturn.” I wanted to mark its publication by returning to the landscape that had inspired the earlier book, and recently I rented a house in Walberswick and set out to retrace Sebald’s progress through the Suffolk countryside.

His journey began in a grand house in north Suffolk called Somerleyton. He visited the fishing port of Lowestoft, and then walked down the coast to Southwold. The Sailors Reading Room, which he said was “better than anywhere else for reading, writing letters … or … simply looking out on the stormy sea as it crashes on the promenade,” inspired another of his meditations. The Reading Room is a shrine to Southwold’s maritime past: ships’ figureheads and framed photographs of trawlermen with names like Workie Upcraft hang on the walls, and copies of local and national papers lie beside “treatises on sailing” and nautical journals on the tables. Having picked up and put aside the log-book of the Southwold, a patrol ship anchored off the pier from autumn of 1914, Sebald noticed a “thick, tattered tome” that “turned out to be a photographic history of the First World War.”

He was drawn to photographs of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, which marked the start of the “chronicle of disaster,” and the next day, he was sitting in the bar of the Crown Hotel, when he came across an article in the day’s paper that “related to the Balkan pictures.” It was about the “so-called cleansing operations” carried out by the Ustasha, a Croatian miliatia, during World War II, and it described a photograph “taken as a souvenir … in which fellow militiamen in the best of spirits … are sawing off the head of a Serb named Branco Jugic.” The atrocity took place at Jasenova camp on the Sava, where the Ustasha killed 700,000 people “in ways that made even the hair of some of the Reich’s experts stand on end.” Sebald is transfixed by the details: “the preferred instruments of execution were saws and sabres, axes and hammers, and leather cuff-bands with fixed blades that were fastened on the lower arm … for the purpose of cutting throats.”

Yet it is not just the acts of brutality that compel his attention: it is the ways in which they are licenced by authority. One of the German intelligence officers who documented the Ustashas’s crimes was a young Viennese lawyer who later became secretary general of the United Nations: “And reportedly it was in this last capacity that he spoke onto tape, for the benefit of any extra-terrestrials that may happen to share our universe, words of greeting that are now … approaching the outer limits of our solar system aboard the space probe Voyager II.”

Sebald has moved from the peace of the Reading Room via the horrors of World War II to the revelation that we are broadcasting evidence of our corruption through the universe with such rapidity and subtlety that you barely notice the transitions: I have read The Rings of Saturn several times, but I often find myself retracing its long, dense paragraphs, looking for the moments when it makes the startling changes of direction that seem, in hindsight, so natural and inevitable.

The next morning, he leaves the town, and crosses the bridge above the Blyth, on his way to Dunwich, a vanished town that exemplifies “the immense power of emptiness.” At first, he thinks he will never reach it: “It was as if I had been walking for hours before the tiled roofs of houses and the crest of a wooded hill gradually became defined.” Dunwich used to be one of the largest ports in England, but it was destroyed by a storm on New Year’s Eve 1285, and another on 14 January 1328. Since then, the sea has continued the steady process of scouring away the land on which it stands: 12 parish churches have disappeared beneath the bay, and today Dunwich consists of a single row of houses, a pub and museum.

Sebald left at midday, and walked “through an overgrown scrubland” before Dunwich Heath opened out in front of him, “shading from pale lilac to deepest purple … with a white track curving gently through its midst.” Yet this was no bucolic idyll: “Lost in the thoughts that went round in my head incessantly, and numbed by this crazed flowering, I stuck to this sandy path, until to my astonishment, not to say horror, I found myself back at the same tangled thicket from which I had emerged about an hour before, or, as it now seemed to me, in some distant past.” The only discernible landmark—“a most peculiar villa with a glass-domed observation tower”—kept appearing and re-appearing “now close to, now further off,” and the signposts gave no directions. Forced to retrace his steps several times, he found himself overcome by panic: “The low, leaden sky; the sickly, violet hue of the heath clouding the eye; the silence which rushed in the ears like the sound of the sea in a shell; the flies buzzing about me—all this became oppressive and unnerving.”

When he finally emerged in “a country lane,” he felt as if he had “jumped off a merry-go-round.” Yet he had still not escaped: months later, he found himself back on Dunwich Heath in a dream that culminated in a vision of Lear, a “solitary old man with a wild mane of hair … kneeling beside his dead daughter.”

Still, at least he could say he got there. When I set out for Dunwich Heath one afternoon, I walked through the marshes south of Walberswick on my own, but I met my wife and children on Dunwich beach, and found myself encumbered in a way that Sebald never was. We followed the footpath that runs along the edge of the eroding cliffs, past the 14th-century friary that is the only surviving relic of medieval Dunwich, but we didn’t get far along the road to Dunwich Heath: the kids were so tired they kept threatening to stray into the path of the cars that careered down the narrow lanes like bowling balls, and after half a mile, we turned back.

Of course, the failure of our family outing hardly mattered, for The Rings of Saturn can be relived by reading and re-reading. After he completed his walk, Sebald, or his unnamed narrator, “became preoccupied not only with the unaccustomed sense of freedom” he had discovered in Suffolk but also with “the paralysing horror that had come over [him] at various times when confronted with the traces of destruction, reaching far back into the past, that were evident even in that remote place.” A “year to the day” after he began his “tour,” he was “taken into hospital in Norwich in a state of almost total immobility.” He was “overwhelmed by the feeling” that “the Suffolk expanses” had “shrunk once and for all to a single, blind, insensate spot.” The Rings of Saturn was his response: “It was then that I began in my thoughts to write these pages” His act of generosity in re-animating his memories makes the Suffolk countryside—and the many worlds he discerned beyond it—available to us all.