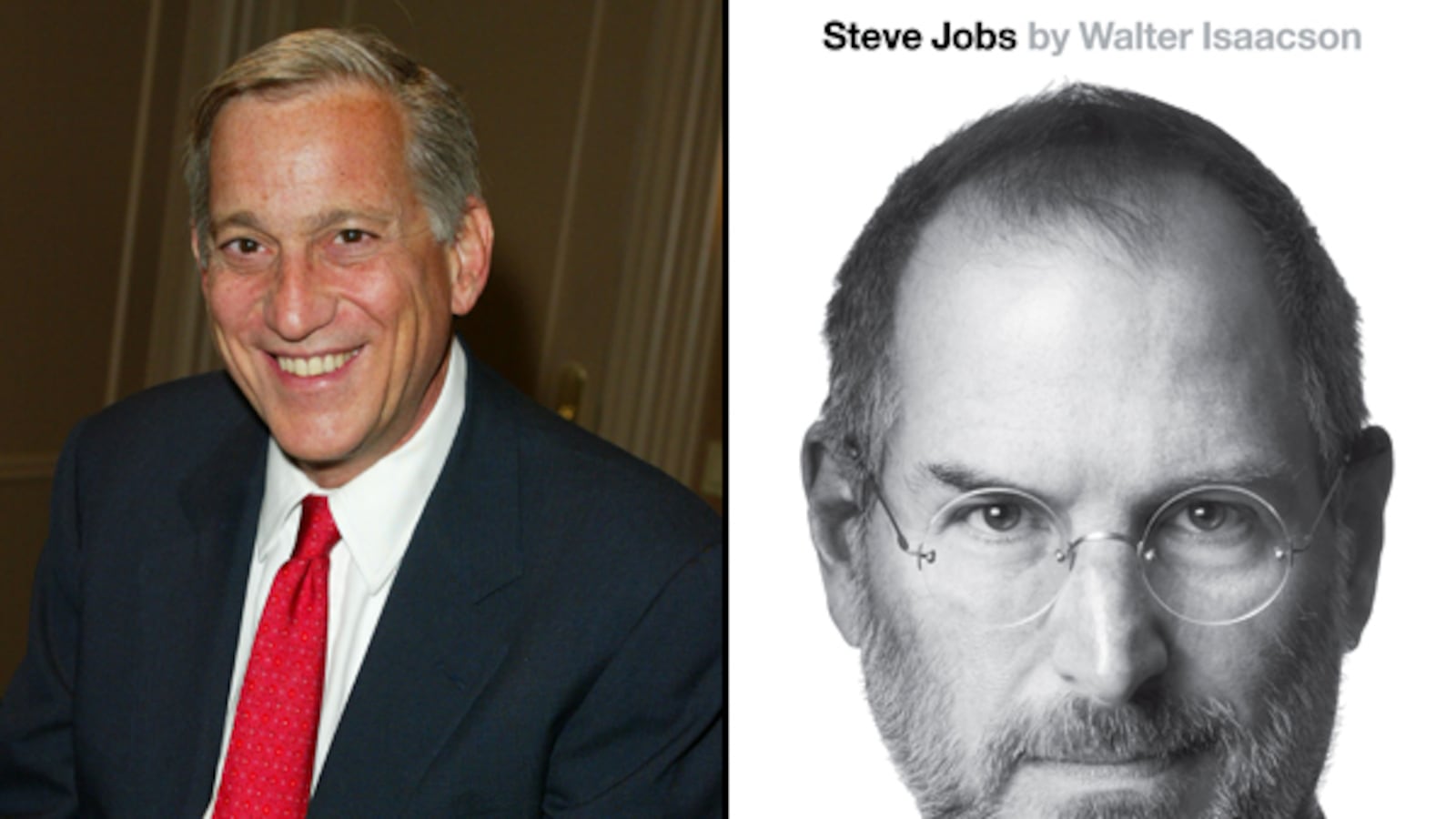

Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Steve Jobs is the smash-hit book of the year, but Isaacson is dismayed that so many journalists writing about the book (myself included) have latched onto the anecdotes about Jobs behaving like a monster to the people around him, without setting those anecdotes against the larger picture of everything that Jobs accomplished in his life.

“You have to judge people by the outcome,” says Isaacson, the former editor of Time magazine who has written bestselling biographies of Benjamin Franklin and Albert Einstein and who is also president and CEO of the Aspen Institute, a nonprofit focused on education issues.

“In the end, Steve Jobs had four loving children who were all intensely loyal to him and a wife who was his best friend for 20 years. At work he ends up with a loyal professional team of A players at Apple who swear by him and stay there, as opposed to other companies that are always losing good talent. In the end he was an inspiring person. He inspired loyalty and real love. So you judge him by that.”

Also worth noting, Isaacson says, is that when it came to tough talk, Jobs could take as well as give. Jobs respected and even rewarded people who would argue with him. “In the early days at Apple they used to give an award to whoever stood up to Steve the best,” Isaacson says. “Those people often ended up getting promoted.”

Jobs died on Oct. 5 at the age of 56 after battling cancer for many years. Isaacson, who spent two years working on the book, has fond memories of dinners with the Jobs family in their home in Palo Alto, Calif., sitting around a big wooden table in the kitchen beside a brick pizza oven. He and Jobs went for walks around the neighborhood or sat in the garden behind the house, talking. They went for long drives, with Jobs showing Isaacson the sights of Silicon Valley, including the house in Los Altos where Jobs grew up, and where Apple began as a tiny project in the garage.

Isaacson was surprised by how modestly Jobs lived—“no security, no drivers, no entourage, no live-in help,” he says. The house where Jobs lived with his wife, Laurene, and their children has no hedges or high walls, no long driveway. Out back is a vegetable and flower garden with beehives from which the family collects their own honey. “It was a house that you would not turn your head to look at as you go down the street. It was built in the 1930s and has no lavish spaces, no McMansion qualities. It’s just a normal Palo Alto neighborhood home,” Isaacson says.

The Jobs household is a calm place, Isaacson says, where dinner conversations centered around things like daughter Eve’s horseback riding but sometimes veered into loftier topics like how to improve schools in America. One evening the family questioned Isaacson about Benjamin Franklin and the American Enlightenment.

Dinners were simple affairs with vegetables from the garden, and perhaps some fish, prepared by a cook who arrived in the afternoon to prepare meals. “What’s astonishing is how normal a family life it is. Steve just never went out socially. He was home every evening,” Isaacson says.

Much credit for the normal home life goes to Laurene, whom Isaacson describes as “sensible and smart and strong,” adding that “she can stand up to him but is also secure enough not to always have to be asserting herself. She combines the romanticism in Steve with the sort of sensible businesslike side of Steve. She could connect to both parts of him.”

One poignant moment in Isaacson’s book comes toward the end, when he describes how, as he was finishing the biography, Laurene told him that Erin, the middle daughter, wanted to be interviewed. Of the three children Jobs had with Laurene (he had an older daughter, Lisa, from a previous relationship), Erin was the one to whom Jobs had paid the least attention, Isaacson writes. She had just turned 16 when Isaacson was writing the book, and he had not asked to interview her, but since she wanted to talk, he agreed. What she wanted to tell him was that she understood why her father had sometimes overlooked her, and that she did not mind. “Sometimes I wish I had more of his attention,” she tells Isaacson, “but I know the work he’s doing is very important and I think it’s really cool, so I’m fine. I don’t really need more attention.”

Jobs and Isaacson first met in 1984, when Jobs was pitching the original Macintosh to editors at Time. “We knew each other on and off,” Isaacson says. “We weren’t pals.” Jobs first approached him about writing the biography in 2004. Isaacson demurred. Jobs asked again in 2009, and this time Laurene explained to Isaacson that Jobs’s health was worse than most people realized, and that “if you’re ever going to do a book on Steve, you’d better do it now.”

Jobs’s brusque side came through sometimes in his interviews with Isaacson. “He’d tell me I was full of shit,” Isaacson recalls. But Jobs was eager to tell his story, and over time the two men grew close. “It got deeper and more intimate the more we talked,” Isaacson says. “I liked him. I understood his passion, and I appreciated the fact that he was brutally honest with people. Steve told me, 'Yes, I’ve been tough on people, but brutal honesty is the price of being in the room, and people can be brutally honest back to me.’”

Jobs reckoned that being tough was the only way to keep Apple from suffering what he called a “bozo explosion”—meaning that if he tolerated mediocre people, they would hire others like themselves, and soon there would be a company filled with employees who weren’t very good. One of Jobs’s great strengths was his ability to spot talent and to inspire gifted people to do their best work.

Thanks to Jobs, Apple today boasts the strongest lineup of executive talent of any company in the history of the tech industry. “Steve’s goal was to create a company that would still be here generations from now,” Isaacson says. “He wanted to build a company that would last. He wanted to ingrain in people this belief in making products that are both artistic and well engineered.”

In August, a few days before he resigned, Jobs invited Isaacson over for a visit and asked him whether there would be parts of the book he would not like. Isaacson told him there would be. Jobs approved, saying that “it won’t seem like an in-house book.” Then he said something strange—that he would wait a year to read the book so that he wouldn’t get angry. “I thought, great, he’s going to be around for a while,” Isaacson says. “He thought there would still be more medical therapies that would let him jump to the next lily pad and keep ahead of the cancer. I finished the book thinking and hoping that he was going to read it next year and, frankly, yell at me for parts of it.”

Instead, six weeks later, Jobs was gone. Nevertheless, he did manage to get his story down on paper before he died. Isaacson’s 656-page book will not be the final word on Jobs, but it offers by far the fullest, richest, deepest accounting of Jobs that has been written so far, offering a rare glimpse into the personal life of a reclusive genius.