Midway through Walter Isaacson’s luminous new biography, Leonardo Da Vinci, the artist of rising reputation moves from Milan to Florence, and in 1502 agrees to meet the warlord Cesare Borgia. Leonardo at this point is fifty-three, handsome, a success, with a keen eye for elegant form, and happily coupled with a younger man.

Milan had given Leonardo his launch, stability and continuing work. He went back to Florence, where he was from, for new opportunities and commissions. Meanwhile, leaders of Florence, an artistic and commercial power, paid Borgia 36,000 florins in protection money, bribing him not to attack the city.

“Name any odious activity and Borgia was the master of it: murder, treachery, incest, debauchery, wanton cruelty, and corruption. He had a brutal tyrant’s hunger for power combined with a sociopath’s thirst for blood,” writes Isaacson. After some seasoning of gory proof, the author adds: “His only sliver of historical redemption, which is undeserved, came when Machiavelli used him as a model of cunning in The Prince and taught that his ruthlessness was a tool for power.”

Machiavelli has a brief role in the build-up to Leonardo’s encounter with Borgia. The Florentine diplomat-writer, “well-educated but poor,” goes with an influential priest to see Borgia, who had been made a cardinal at eighteen but stepped down after showing “less than zero predilection for piety.”

Simon and Schuster in the book’s press release has disclosed that Leonardo DiCaprio optioned the film rights. Picture Leo as Leonardo, nervous over Machiavelli’s negotiations. Cut to Andy Garcia as Machiavelli, fearful in his approach with the priest inside the ducal palace at Urbino, east of Florence, where the evil Borgia (Al Pacino? Robert De Niro?) sits wizened and coiled. The book continues:

“Borgia knew how to put on a power show. He was seated in a dark room, his bearded and pockmarked face lit by a single candle. He insisted that Florence show him respect and support. Once again a vague accommodation seems to have been reached, and Borgia did not attack. A few days later, probably as part of his arrangement with Florence that Machiavelli had helped to negotiate, Borgia secured the services of the city’s most famous artist and engineer, Leonardo da Vinci.”

There’s room for the great facial gesture in a movie where the pastoral Leonardo recoils in horror as Machiavelli puts the deal on the table: We don’t want him butchering people or burning our beautiful city, eh? A marvelous plot turn: the great painter of Leda and the Swan (his masterpiece Mona Lisa yet to come) eyes the calculating political writer. Machiavelli hammers home the demand: You must go to Borgia!

Real life is more prosaic. One beauty of historical narrative lies in learning of the strange accommodations people make to the unexpected, how people change, as events evoke mysteries of the self.

To this point in the book, Isaacson has guided us from Leonardo’s impoverished, if happy, out-of-wedlock boyhood with doting grandparents; unprivileged early schooling, his father’s role in securing him an apprenticeship at fourteen to the studio of the artist and engineer, Andrea del Verrochio in Florence; the early drawings, widespread interests in nature and form, the move to Milan and astonishing run of Milanese portraits, religious paintings and a shimmering chapter on the narrative properties he brought to bear in painting one masterpiece, The Last Supper.

And then comes Borgia, evil incarnate. The notebook drawings he did of Borgia, and sketches of battle scenes over the better part of a year, barely hint at Leonardo’s motivation. Apart from the prestige of having Leonardo da Vinci on payroll, Borgia gave him work as a military engineer and map-maker. Leonardo was long fascinated with how birds fly, the vast interconnectedness of nature, the way water moved, how bridges were built. In Isaacson’s account, which makes substantial use of Da Vinci’s voluminous notebooks, Leonardo was not overpowered by Machiavelli, nor forced by Florentine rulers at metaphorical sword-point to butter up the bloody warlord.

“Leonardo may have gone to work with Borgia at the behest of Machiavelli and Florence’s leaders as a gesture of goodwill,” writes Isaacson. “Or he may have been sent as a way for Florence to have an agent embedded with Borgia’s forces. Maybe it was both. But either way, Leonardo was no mere pawn or agent. He would not have gone to work for Borgia unless he wanted to.”

He had reason to take the job. Traveling with an army exposed Leonardo to hydraulic issues and logistical challenges far from the privacy of painting – challenges like bridge building that engaged his imagination. The military excursions exposed him to cruelty. Riding with Borgia’s troops on a conquest of Siena, he learned that one of his friends has been strangled during the invasion. “His notebooks suggest that he had mentally tuned out Borgia’s horrors by focusing on other matters,” writes the biographer. Leonardo enjoyed “a chance to live out his military fantasies, which he did until he realized they could become nightmares.”

Leonardo Da Vinci is an elegantly illustrated book that broadens Isaacson’s viewfinder on the psychology of major lives – Henry Kissinger, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs are the subjects of his previous biographies, best-sellers all. He began the research on Leonardo ten years ago, and spent the last three years writing, in after-hours and vacations as CEO of the Aspen Institute, an education and policy studies organization in Washington, D.C. and Aspen, Colorado. Isaacson was previously Chairman of CNN, and Editor in Chief of Time.

The Daily Beast asked him how an artist with such interest in anatomy and the human body could follow an army as it slaughtered people.

“He does it for a year and quits,” said Isaacson in the present-tense favored by scholars in fostering proximity to their topics. “Leonardo is a gentle person, a vegetarian at times, and suddenly he’s there with Machiavelli working for Borgia. They both quit after a year. It shows his fascination with the military, and the desire of the engineer, which he’d had for much of his life, conflicting with the sweetness and gentleness of his artistic nature. He does a big drawing -- the fighting he depicts is brutal, people decapitating each other up close, but he never paints the painting. Peter Paul Reubens did a mural based on Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari. But Leonardo goes back to Milan and works on the Virgin on the Rocks, one of the most peaceful works of art imaginable. You can see the conflict between his love of engineering and being a kind person. In the end, his sweetness wins out and he leaves Florence.”

What explains the biographer’s pole vault from Steve Jobs and the Apple saga, back in time to Renaissance Italy?

“I’d always written about people who were really smart but I began to realize that smart people are dime a dozen,” says Isaacson. “What matters is being creative in applying one’s imagination to a problem. The most creative people seem to be cross-disciplinary, liking arts and sciences. Leonardo is much more than a combination of Jobs, Einstein and Franklin. He left us 7,000 pages of notebooks. To study the pages of his notebooks was dancing with the most creative and curious mind in history. People have written about his art. I wanted to talk about how he was born illegitimate, couldn’t go to college, and in teaching himself, followed a relentless curiosity that saved him from accepting the received wisdom of his day.”

Isaacson’s first exposure to a Da Vinci texts came in Seattle, while attending a conference. Microsoft founder Bill Gates showed him a Da Vinci document he had purchased. “Bill Gates and his curator were kind enough to give me an early copy of the new translation they plan to publish in two years of the Codex Leicester,” he told The Daily Beast.

Isaacson had translation assistance from a scholar in Florence. “I went to see the notebooks and discuss them with experts in Milan, Florence, Venice, Paris, Madrid, Windsor Castle and Seattle. For ten years, I was fascinated whenever I could go and see a Leonardo notebook, like the codex on the flight of birds that was exhibited in New York, at the Morgan Library, a few years ago. Following his notebooks was like engaging with the most curious, observant friend in history. You look at pages on which he draws a fetus in the womb, or in his sketches for The Last Supper, or making a square inside the area of a circle, and it’s like seeing his mind as it’s moving.”

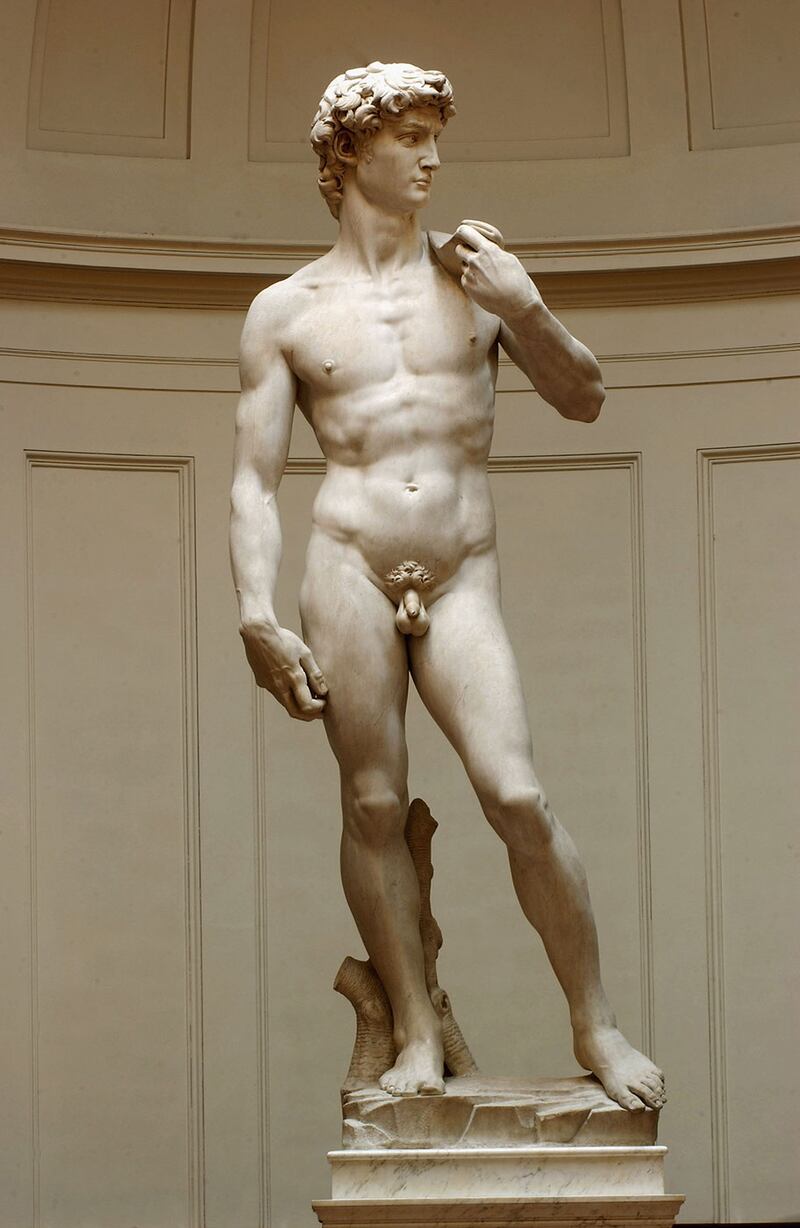

Twenty pages after Leonardo safely leaves the employ of the marauding Borgia for the familiar life in Milan, we find him back in Florence. It is 1504; he attends a meeting of notables who are trying to decide on placement of “the most famous statue ever carved,” writes Isaacson. This is the seventeen-foot high, “dazzlingly bright” figure of David by Michelangelo.

“Florence’s leaders were then faced with the question of where to place this astonishing colossus,” he writes. Inside a major building, outside in a palazzo? “The issue was so contentious that there was even an outbreak of stone-throwing by some protestors. Being a republic, Florence formed a committee. Thirty or so artists and civic leaders were convened to discuss the issue.”

Botticelli, who painted the serenely majestic Birth of Venus and was so captivated by Dante’s The Divine Comedy as to do classic illustrations of the poet’s spiritual quest, sat on the committee, too.

Here we encounter an ironic tic in Da Vinci’s personality.

“Michelangelo had sculpted David unabashedly naked, with prominent pubic hair and genitalia,” writes Isaacson. “Leonardo suggested that a decent ornament be attached ‘in such a way that it does not spoil the ceremonies of the official’ “ – in other words, cover the penis of the colossus. In a notebook drawing, Da Vinci sheathed the member of David the Goliath slayer “with what looks like a bronze leaf.”

Da Vinci’s strange response to Michelangelo’s supreme sculpture stemmed from the radically different personalities of the two Renaissance artists. Both were homosexual; Leonardo was comfortable in his skin and for all of the grandeur and delicate beauty he imbued in his religious paintings, had no interest in a Catholic spiritual life. In contrast, Michelangelo was devout, and so repulsed by his sexual orientation as to be celibate, according to Isaacson. The book continues:

“Leonardo was quite comfortable and open about having male companions. Leonardo took delight in clothes, sporting colorful short tunics and fur-lined cloaks. Michelangelo was ascetic in dress and demeanor; he slept in his dusty studio, rarely bathed or removed his dog-skin shoes, and dined on bread crusts.”

For an artist like Da Vinci, covering David with the proverbial fig leaf, albeit fabricated, seems a puritanical aberration, if not a contradiction; yet he prevailed, and for at least forty years Michelangelo’s masterpiece had “a gilded garland made of brass and twenty eight copper leaves.” writes Isaacson.

In the interview, Isaacson considered the contradiction.

“Leonardo was comfortable drawing pictures of nudes. I don’t think he was prudish. Leonardo was very much the dandy as dresser. I think he thought Michelangelo lacked a little bit of grace and style.”

Leonardo was also a generation older than Michelangelo, long-established, secure in his personality -- a confidence that Michelangelo for all of his towering talent could only hope to emulate. Financially beholden to the papacy, often vexed by the warrior-pope Julius II, Michelangelo endured physical excruciation in painting the Sistine Chapel. Leonardo “did not dance to the tune of patrons,” says Isaacson.

His rationale for that fig leaf over the majestic David tells us more about the older artist’s cold pragmatism, detecting the limits of a Florentine establishment on where to put such a bold work.

In his own career Leonardo, by then fifty-two, had achieved a plateau where he could pursue pretty much what he wanted. “The richest woman in Italy wanted him to paint her portrait and he keeps refusing,” says Isaacson, warming to his subject. “Instead he does Lisa, the wife of a middle class Florentine cloth merchant; he does it for his own satisfaction and never delivers it. He very rarely delivered finished paintings to patrons; he painted for himself.”

As Isaacson details in the chapter on Mona Lisa, Leonardo’s fascination with the human smile became an obsession in the many years he worked and reworked the famous painting, now in the Louvre. Those years coincided with his sessions in a hospital morgue near his studio in Florence, “peeling the skin off cadavers and studying the muscles and nerves underneath” to sate his curiosity over anatomical properties of the human smile. He was equally obsessed with light patterns that would, over time, enhance the mystery of the painted woman’s fabled smile.

“His genius comes not because he was touched by the heavens like an Einstein with mental powers,” says Isaacson. “It came because he willed it -- he invented himself as someone who was curious about every tiny thing in this world including how we fit into it. He was observant of how a dragon-fly’s wings move, and the flow of water when it hits pond. He was a self created genius. Today we silo things, expecting people to be engineers, or learn coding, or become specialists. Leonardo teaches us the magic and creativity that comes with dancing across different disciplines by indulging fantasy.

“He’s quite relevant as we think about how to raise children. We’re unlikely to raise an Einstein, but we can indulge our children’s curiosity with a willingness to help them enjoy fantasy. Leonardo wasn’t categorized only by his interest in music and art – he had that boundless curiosity for anatomy, engineering and human flight. We can nurture that curiosity in children, encouraging them to see that it’s fun to understand art and science, standing at that intersection is where creativity occurs.”

Isaacson is in his last year as CEO of the Aspen Institute, phasing out as he resettles in New Orleans. In 2018 he will become a university professor at Tulane. Mayor Mitch Landrieu has appointed him to the City Planning Commission. In a May 10, 2006 essay on New Orleans for Time, entitled, “How to Bring the Magic Back,” Isaacson assessed the post-Hurricane Katrina city, then a broken mud town, stalled in an aching recovery, and struck a tone of optimism that, when read today, has a ring of prescience. Landrieu’s seven years as mayor have seen a city substantially rebuilt, economically rebooted with a grassroots film industry and digital economy. Eleven years ago, Isaacson wrote:

The city needs to restore itself authentically rather than produce a theme-park re-creation. It needs shotguns, not cold condos. Its talented preservation and community-planning experts should be offered the chance to devise a land-use approach that revives charming old neighborhood patterns rather than producing alienating cul-de-sacs or artificial quaintness. It has the opportunity to rebuild itself in a way that emerges from its rich heritage while guarding against any projects that would sap its soul.

So why leave a super-charged media life in Washington, to burrow down on zoning issues at the bottom of America?

“The simplest explanation is that I love New Orleans. It’s where I grew up,” says Isaacson. “The more complex answer is that those of us from wonderful communities who have the good fortune to go off and do things like edit Time or run an institute in Washington, tend to lose touch with our roots, and we become part of the divide in America -- coastal elites as opposed to people grounded in their communities, searching for here-and-now solutions. Hurricane Katrina hit me hard. I worked on the Louisiana Recovery Authority, and got re-engaged. I learned that if you cling to Washington your whole career, you’re alienated from what really matters, your community. Some people stay away from their home towns, but at a certain point they should think about where they belong. Not everybody wants to go back. I decided I wanted to return to the place that matters most to me.”

Jason Berry, the author of Render unto Rome; The Secret Life of Money in theCatholic Church, is at work on a history of New Orleans.