It was March 17, 1982—St. Patrick’s Day—and James Powers was in the middle of his shift at the Purolator armored truck terminal in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he worked as a security guard.

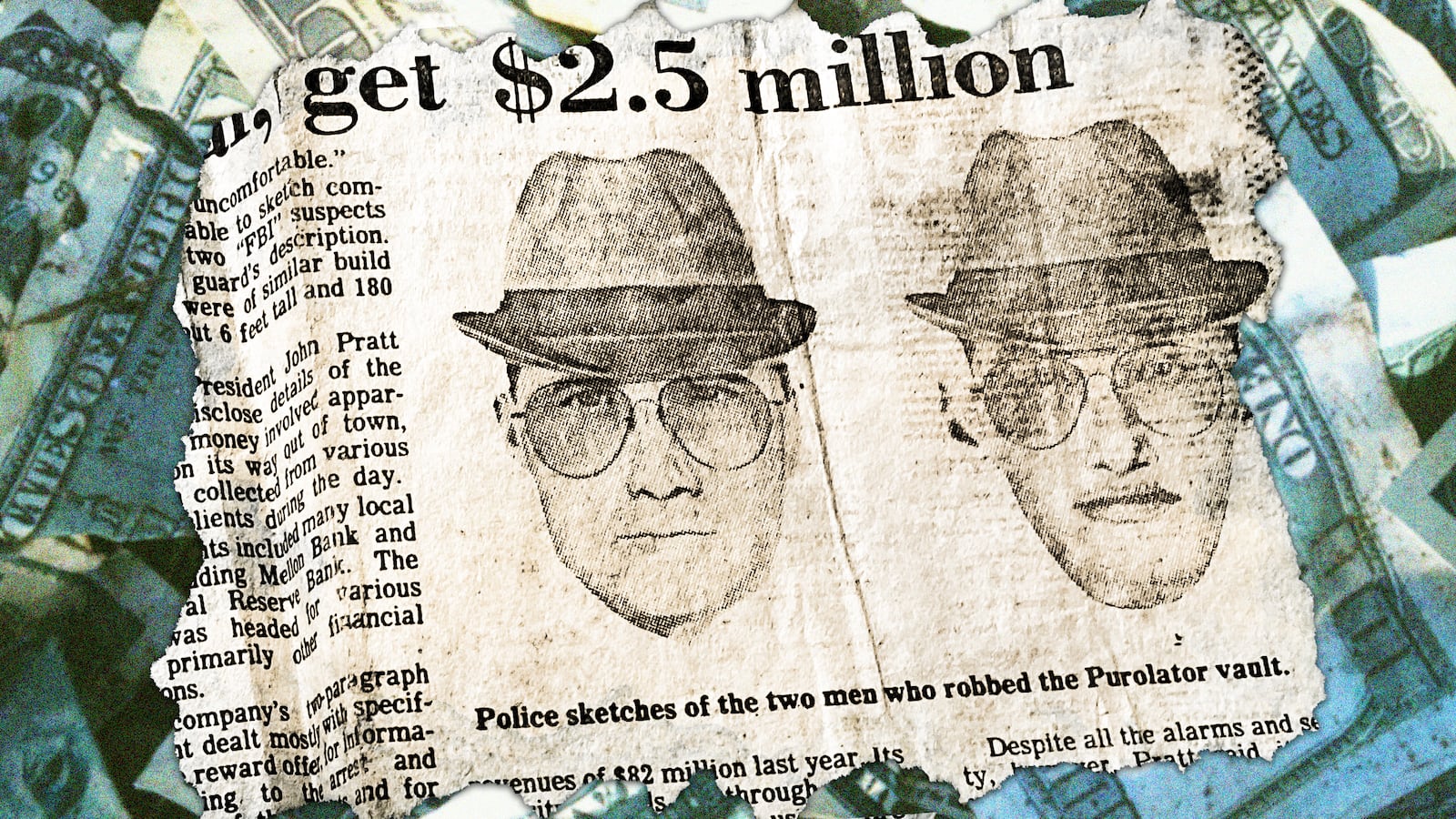

At about 11:30 p.m., two men wearing trench coats, dark felt hats, and aviator sunglasses ducked under a garage door as a truck left the depot to make a delivery. The men, one white and one Black, were roughly 6 feet tall and each carried a walkie-talkie. Once inside, they approached Powers, who was the only guard on-site that night, and introduced themselves as FBI agents while flashing their credentials.

The pair told Powers, 54, that the FBI had received a tip warning that the facility was going to be robbed. And that’s when they did exactly that.

After overwhelming Powers and grabbing a shotgun from his hands as well as a pistol from a holster on his hip, the intruders handcuffed him, tied his legs together, taped his mouth and eyes shut, and forced him to lie on the floor in an employee lounge. The men then used Powers’ keys to access a vault area, taking some 26 bags of cash waiting to be delivered to banks across western Pennsylvania.

Although he couldn’t see them, Powers could hear the men wheeling the loot out of the vault on metal carts. Once they were done, they summoned a getaway driver waiting outside, who drove into the loading bay. When the money was loaded into the vehicle, the fake FBI agents drove off into the night. They got away with approximately 500 pounds of cash, worth $2.5 million in all. Adjusted for inflation, that’s more than $7.2 million in today’s dollars.

With his hands still cuffed and his legs bound, Powers worked the tape from his mouth and managed to get to a telephone. Feeling his way around the rotary dial, Powers twice tried to dial ‘0’ for the operator but couldn’t get through. He then tried to call his supervisor, but dialed the wrong number. When he asked the woman on the other end of the line if Larry was there, she said no. “Don’t hang up!” Powers pleaded, and asked the person who answered to call the police. A swarm of cops arrived around 1 a.m., and Purolator soon put up a $100,000 reward.

In capers like this, someone on the inside is often involved. The FBI quickly zeroed in on Powers, but he was eventually cleared of any wrongdoing. Still, Purolator fired him a month after the depot was hit; he died in 1996.

“All I remember from the time is that he was extremely upset over the whole situation,” Powers’ son Edward told The Daily Beast this week. “He was questioned, nothing came out of that.”

Now 66, Ed Powers was in his twenties at the time. He said he was “never called in for anything” by investigators, and that he has thought little about the incident in the four decades since.

“After it happened it slowly just ventured into quietness,” said Powers. “I guess I could say it that way.”

To this day, the Purolator heist remains one of the biggest robberies ever in the Pittsburgh area.

In the aftermath of the holdup, FBI agents were stumped.

Investigators methodically eliminated a handful of possible suspects, including a Pittsburgh police officer who quit the force a few days after the heist.

At one point, the bureau reportedly attempted to hypnotize a witness who said they had seen the getaway car, to find out if they could conjure up a license plate number.

It didn’t work, and the case went cold.

“We’ve had lots of calls and we’re sorting them out,” Pittsburgh FBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge Tony Daniels said at the time. “But we've basically got nothing.”

A little less than two years after the Pittsburgh holdup, Purolator sold its armored car subsidiary to Mayne Nickless Ltd., an Australian company that already owned the Loomis Armored Car Service, for $33 million in cash.

“Nothing has ever been found out about the case, [and] whoever did the burglary was never caught, as far as I know of,” Ed Powers told The Daily Beast. “They believe it was carried out by a local mobster here.”

The one person who raised multiple eyebrows within the FBI was Eugene “Geno” Chiarelli, a ranking member of the Pittsburgh La Cosa Nostra. Chiarelli was born in the Calabria region of southern Italy and raised in the Pittsburgh suburb of New Kensington. He served as a military policeman in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1961 to 1965, spending part of his hitch stationed in Okinawa.

A carpenter by trade, Chiarelli was an earner for the LaRocca Family, making his bones in large-scale cocaine trafficking, extortion, and robbery.

Chiarelli, who died in 2012, had been involved in running the Showboat Club, a mob-connected Pittsburgh nightspot that in 1972 went out of business under suspicious financial circumstances. At the time, Chiarelli was living in a Hilton in downtown Pittsburgh after his house—a $35,000 split-level that was insured for twice that—burned down in a fire authorities believed was arson.

“He was quite the colorful individual,” Chiarelli’s son Robert told The Daily Beast.

Robert Chiarelli, now 50, still lives in the Pittsburgh area, where he runs a general contracting business. The only child of Geno and Charlotte Chiarelli, he remembers his dad as a lovable raconteur who told endless real-life tales.

“When you sit around the table hearing these stories firsthand, it was pretty entertaining,” Chiarelli said, declining to confirm or deny his father’s alleged role in the Purolator robbery.

But he added, “I could tell you enough for you to write 50 pages on this Purolator thing. And it’s not just Purolator. There’s a whole bunch of things that would make a book or a movie, that would sell tons of copies or tons of tickets.”

In 1987, Lawrence Likar, a young FBI agent working violent crime out of the bureau’s Pittsburgh Field Office, decided to take his own look at the Purolator robbery as a cold case. Five years had passed, and investigators had gotten nowhere.

“Most of the time in armored car cases, generally you have really strong, tough guys who do those,” Likar told The Daily Beast. “Money weighs a lot, and sometimes you’d have to muscle people around.”

The “only person” Likar recalls even looking into was Geno Chiarelli, he said, explaining that Chiarelli was an imposing figure who was also “good with tools,” an important skill when dealing with safes and vaults.

Chiarelli was already the prime suspect in the 1985 disappearance of Pittsburgh mob associate Joseph Bertone, a 49-year-old restaurant owner and cocaine dealer locked in a feud with Chiarelli and a local mob associate, Joey Rosa, over drug proceeds. Bertone had an extensive criminal history, and his eatery, Joey’s, was firebombed in 1978, rebuilt, then finally leveled completely in a 1982 explosion. When he went missing, Bertone was wearing two gold rope chains and a wedding ring with the name “JOEY” spelled out by 15 individual diamonds circling the band. Bertone’s Cadillac Seville was found 10 days later in the parking lot of a nearby Holiday Inn. His body has never been found.

Chiarelli was also under the microscope for his role in a 1986 bank heist in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, in which burglars disconnected the alarm system, sawed through the roof, and drilled their way into the bank’s vault, making off with 16 Renaissance-era wheellock pistols and an antique Augsburg hunting sword worth a combined $2 million.

“He was a tough guy and he kept his mouth shut,” said Likar. “I never had anything on him.”

Likar described Chiarelli as a “long-term member of the mob,” and said he “never turned on anybody.”

Thus, few people were willing to turn on him. Until one did.

In December 1987, Chiarelli and three others were busted in Florida after trying to sell the weapons from the Greensburg bank back to the insurance company for $385,000. But Chiarelli escaped during a high-speed car chase through the streets of Tampa, and made his way back to Pittsburgh, where he surrendered to police a few days later. All four members of the crew were indicted by a federal grand jury in January 1988 on charges of possession and transportation of stolen property. No one was ever charged for the burglary itself.

“My dad went to court and ended up [being found] guilty,” Robert Chiarelli told The Daily Beast. “I have the firsthand account on all of this from my dad.”

Sentenced to 40 months in federal prison, Chiarelli’s luck would soon take another turn for the worse.

In April 1990, he was indicted as part of an expansive prosecution under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act that would essentially put the Pittsburgh mob out of business.

One of nine defendants, Chiarelli was accused of supplying the gun used to kill Joseph Bertone, along with racketeering, conspiracy, and possession with intent to distribute cocaine. Joey Rosa had already been convicted on federal drug charges and came back to haunt his old pal Chiarelli.

“He was the star witness in the case, and he was the guy that turned state’s evidence against the group,” Robert Chiarelli told The Daily Beast. “Rosa was nothing. He was a guy who got caught selling drugs, and then tried to use [his testimony] as a way to reduce his sentence.”

In September 1990, Rosa testified that, among other things, Geno Chiarelli told him that he had been the one behind the Purolator heist.

Chiarelli was convicted of racketeering and drug trafficking, and sentenced to 22 years.

But no charges would ever come out of the Purolator case. In 1987, the statute of limitations expired—and it seemed clear that whoever had done it would get away with it.

On June 2, 2008, with time off for good behavior, Chiarelli was released from federal prison. He served the longest sentence of all his co-defendants, and never cooperated with the feds.

After he got back to Pittsburgh, he was diagnosed with lung cancer. Chiarelli died at Robert’s house on June 14, 2012, at the age of 69.

Not long before his death, Chiarelli began writing his memoirs in hopes of one day publishing a book, according to his son. The manuscript, along with hundreds of pages of handwritten notes, have been sitting in a shoebox inside a closet at Robert Chiarelli’s home, where Geno died. Among them were old newspaper clippings about the Purolator heist that Chiarelli had saved his entire life.

“There was some talk about possibly publishing some of that at some point, that maybe helps his grandkids or something—my kids—but I haven't decided if it’s something I want to pursue or not,” Chiarelli said. “I just don’t know if I’m ready to get into all that. I have relatives and friends of his that are still alive, and it’s in the past but I don’t know if I feel like dredging all of that back up again. There’s all kinds of things in there.”

Chiarelli’s obituary in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette called him “one of the few remaining members of the once-powerful Pittsburgh La Cosa Nostra.”

The obit summed up Chiarelli’s criminal career, quoting police and FBI officials who “still marvel at the professionalism on display” in the Purolator heist.

“He was believed to have committed one of the region’s most infamous unsolved crimes,” it said of Chiarelli’s long-alleged link to the daring St. Patrick’s Day score, identifying his partner in the 1982 crime as “fellow carpenter Anthony Durish.”

Joey Rosa and Anthony Durish were unable to be reached.

Armored car heists have fascinated the public since the very first one was pulled off in 1927 in Pittsburgh.

More recently, a 1993 armored car heist in Las Vegas was turned into a Netflix documentary earlier this year. The film, Heist, is based on a robbery carried out by Roberto Ignacio Solis and Heather Catherine Tallchief, which netted the duo $3 million. In 2006, after 12 years on the run overseas, Tallchief returned to the U.S. and turned herself in. She was sentenced to 63 months in federal prison and ordered to pay $2,994,083.83 in restitution. Solis remains a fugitive.

Tallchief, who took a job as an armored car driver at Solis’ behest in order to position themselves for the caper, has declined interview requests for years, and did not allow her voice to be heard or her face to be seen in Heist. When reached by The Daily Beast, Tallchief, who now works in the health-care industry and lives in an undisclosed location somewhere in the continental United States, asked that her new name and whereabouts be kept confidential.

When asked what it was like to live as a fugitive, Tallchief told The Daily Beast, “It sucks. End quote.”

The armored car industry—which prefers the term “cash-in-transit”—is even more tight-lipped about its operations.

“It’s very hard to get people to talk about armored car security, they don’t believe it’s in their interest to do so,” Robert McCrie, a professor of security management at New York City’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, told The Daily Beast. “They almost are sworn to secrecy.”

Each year, somewhere between 25 and 35 armored car robberies are reported. They are generally more violent and involve more cash than traditional bank robberies, of which about 4,000 are reported annually. Houston recently attained the dubious distinction of being the armored car heist capital of America, primarily because its network of freeways allows getaway drivers multiple escape routes, according to one FBI agent.

Nowadays, banks don’t like storing vast amounts of cash on the premises, and have largely outsourced this aspect of the business, said McCrie, who has consulted extensively for armored car companies. Regulation is thin, and standards are largely set by insurers, McCrie said. But margins are also razor-thin in the cash transport game, and wages are comparatively low. This naturally enhances the so-called insider threat, retired FBI agent Dennis Franks told The Daily Beast.

At a cash storage depot, such as the one hit in the Purolator robbery, there can be tens, even hundreds, of millions of dollars at hand. And usually, the only ones who know the precise security procedures in play are those who work there. A successful robbery is practically “impossible… without that insight,” said McCrie.

Although armored cars continue to be targeted in relatively small numbers, the kind of heist like the one at the Purolator depot simply “doesn’t occur anymore, which is good news,” according to McCrie.

To begin with, there are no more simple garage doors allowing easy access in and out, he explained. Modern cash storage and counting facilities feature “truck traps,” which act like vehicular sally ports in which one door must close before the next one opens, said McCrie.

“Organizations are [now] very paranoid about who they let inside,” McCrie continued, describing a facility he recently visited near Baltimore. “The people counting the money were in hermetic cubicles, and there were several TV cameras on them from different angles.”

What was once done by hand is now largely done by machine, from counting to sorting to wrapping the currency, which has also contributed to a decrease in what McCrie termed “internal losses.” Random bundles of money also contain GPS trackers, so if stolen, police can follow the path in real time. Access control is paramount, and nobody—even a pair of FBI agents with genuine-looking badges—is allowed in without a form of two-factor authentication: approval from a supervisor.

It’s something that McCrie says started after Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was robbed in 1990 of 13 masterpieces worth some $500 million by two thieves dressed in police uniforms who were let in to investigate a disturbance they said had been reported.

“That procedural difference has made security greater than it has been in the past,” said McCrie.

Combine that with the increased deployment by cities and law enforcement of high-resolution surveillance cameras, automated license plate readers, and cellphone location data, the chances of pulling off an armored car heist fall dramatically, he said.

“So, it’s kind of risky to try to rob these places but it’s always profitable if you carry it off, as in the case of Purolator,” said McCrie. “They know that there’s cash, and they know that if their modus operandi is right, they’ll probably be able to walk away with some cash and nobody will get hurt.”

To many, the Purolator heist became the stuff of legend.

“It’s the kind of stuff you read about in novels or see in the movies, created by writers,” late Pittsburgh Police Commander Ron Freeman said prior to Geno Chiarelli's death. “This is a crime we rarely ever see.”