On Feb. 28, 1905, Jane Stanford enjoyed a languid day in Honolulu, one that she no doubt needed.

The last decade had been a trial for Jane. There was the death of her husband and the dispute over his estate that put the couple’s passion project, Stanford University, in a precarious financial position. Once that was settled, she faced clashes with the president of the university, David Starr Jordan, over the philosophical direction of the institution.

And then, of course, there was the murder attempt against her earlier that year, one she survived thanks to her sensitive palate.

Her trip to Hawaii wasn’t so much of a reset as it was a swanky hideout. With no suspects in her attempted poisoning, and the investigation only just getting underway, Jane decided to leave California and take refuge at the Moana Hotel in Honolulu.

Feb. 28 was a mild day on the islands, a perfect day for a long picnic overlooking the ocean. Jane’s private secretary, Bertha Berner, whose accounts would prove to be untrustworthy at best and sinister at worst, claims that she was in high spirits that day, singing in the back of the buggy and talking about her plans for the rest of their trip. When Jane returned to the hotel, she took a short rest, chatted with hotel guests, partook of a light snack in lieu of dinner, and then settled into bed a little after 8 p.m, after drinking the bicarbonate of soda she requested from Berner.

Just a few short hours later, the first lady of Stanford University was dead. She did not go gently and she immortalized her excruciating end in the alleged last words, “What a horrible death to die!”

For a century, the suspicious circumstances surrounding the death of Jane Stanford have been nothing more than a footnote in the history of one of the United States’ top colleges. The university embraced the party line that its matriarch had died of natural causes (heart disease), a story that took hold after the investigations into both the first poisoning attempt and her death fizzled out, with the help of the corrupt San Francisco police department.

But at the beginning of the 21st century, that all began to change. In a reversal of the typical murder investigation storyline, the facts of the case have become even more clear 100 years after Jane’s death due to the renewed interest and work of several historians and scholars. While the case officially remains unsolved, today it is more certain than ever that Jane Stanford was most likely murdered and that the culprit was someone very near and not so dear to her.

Jane was a difficult woman, but she was a force of nature—as she had to be, living the life she did at the turn of the 20th century.

Jane married Leland Stanford at the age of 22 when both were of modest means and backgrounds. She was a dutiful wife, living up to the ideal of her times as the helpmate to a husband quickly becoming a railroad baron. She did so even as her own dream eluded her. She desperately wanted to be a mother, but was plagued by nearly two decades of infertility. Finally, at the almost unimaginable (in 1868) age of 39, she gave birth to the couple’s only child.

For 15 years, she devoted herself to her son, Leland Stanford, Jr. He was a precocious child and his every whim was indulged until the devastating day in 1884 when he caught typhoid while the family was on vacation in Europe. He died.

By this time, her husband had bribed and swindled his way into becoming one of the wealthiest and most “successful” businessmen in America. He had already served as governor of California and was gearing up to make a run for Senate.

In the wake of the unimaginable tragedy, the couple decided to add a new cause to their family resume. They announced that they would found an educational institution in San Francisco in honor of their lost son. Jane was a partner in this venture, exerting her influence in many ways including insuring that women were allowed equal entry to the university, a move that was unusual in the world of elite education.

Although sources show that Jane was beloved by many students, she wasn’t a benevolent matriarch. By all accounts, she was demanding and overbearing to those closest to her, and prone to aggressive behavior toward those who weren’t.

As Mary Ann Gwinn wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “She would savagely undercut a rival, and then, as strategic cover, she’d write an admiring letter praising her enemy to the skies. She ordered her servants around— admittedly what one does with servants, but she demanded total obedience. The servants lied in return as self-defense, about both their personal lives and the grift they had going on the side, raking off a percentage from the purchases of antiques they made on Jane’s behalf as her entourage drifted across the globe.”

Stanford University Campus.

David Butow/Corbis via Getty ImagesTowards the end of her life, her biggest adversary was the president of the university.

David Starr Jordan and Jane had worked together during six long and arduous years to keep Stanford afloat after Leland’s death when his estate was in flux. (The government wanted to recoup the outstanding loans they had made to him.) Jane filled in the gaps with her own money where she could, even going so far as trying to sell some of her jewelry, and she was intimately involved in the running and daily management of the university.

“The future of a university hung by a single thread—the love of a good woman,” Jordan later said.

But after the emergency faded away and the estate was resolved in Jane’s favor, the philosophical cracks between the two strong-willed leaders began to emerge. Jane and Jordan had very different ideas about the philosophy that should guide the university (her: liberal arts; him: the sciences), they were on different sides of personnel decisions, and they had fundamentally different belief systems.

Despite having plenty of personal tragedy in his own life, which Lulu Miller writes about beautifully in Why Fish Don’t Exit, Jordan was a man of science to the extreme. The biggest blight on his life and soul is that he was a staunch proponent of eugenics. Jane, on the other hand, had channeled her grief into the popular spiritualism movement. She held regular seances where she would converse with her dead husband and son, and seek their advice on matters including those of the school.

“Ghosts ran the university,” Richard White writes in his recently published book, Who Killed Jane Stanford?.

The clash came to a head in early 1905, when Jane began to take steps via the school’s board, which she ran, to remove Jordan from his position.

On the night of Jan. 14, 1905, Jane went to bed with a bit of a cold. Before lying down, she took a big sip of the water left out for her, and became immediately concerned. It tasted bitter. She began vomiting and then, in an act of true Gilded Age privilege, called in two of her employees to taste it. They agreed something was off. The water was sent off for testing and a few days later the verdict was in: deadly levels of strychnine.

“I am startled and even horrified that any human beings feel that they have been injured to such an extent as to desire to revenge themselves,” Jane wrote to a friend.

It was this fear that drove her to flee to Hawaii. Four days after she left, news of the attempted poisoning broke. While Jane was still in the middle of the ocean, Jordan gave a statement dismissing the incident: “The fact is that Mrs. Stanford was threatened with pneumonia and her physician advised a warmer climate than San Francisco… She did, however, tell me a month ago that she had been served with a bottle of mineral water which had a peculiar taste, but she did not drink it. She did not think for a minute that any attempt was being made to poison her, and I do not believe there was.”

Just over a week later, Jane was dead.

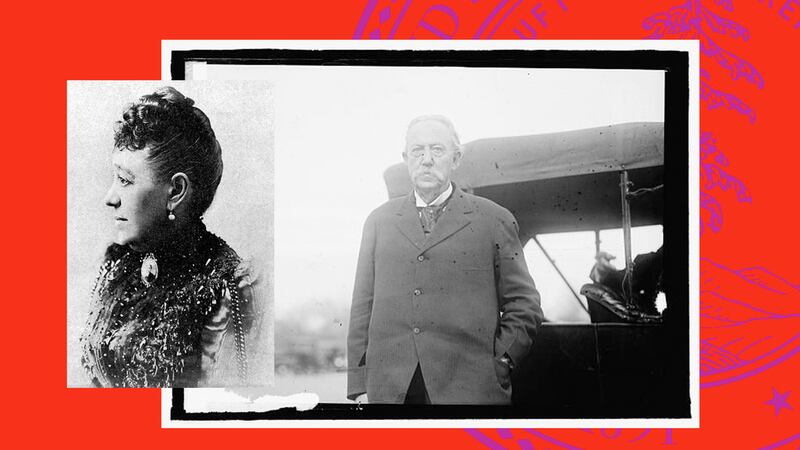

Jane Stanford, left, and David Starr Jordan.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Library of Congress/WikipediaHawaiian officials quickly got to work and an autopsy and testing of the bottle confirmed their initial suspicions—strychnine poisoning. But all involved seemed baffled by who might have a motive to kill her. Money, they correctly deduced, is usually the motivation for killing off a wealthy individual. But, in this case, the authorities believed there was no money in dispute—pretty much the entire estate was to be donated to the university. The only suspects they could come up with were some disgruntled servants.

Despite the fact that the university was Jane’s biggest beneficiary, Stanford never came under suspicion. Regardless, Jordan was quick to launch a fake news campaign to convince the world that there was nothing to see here. He quickly left for Hawaii, where he hired his own medical examiner to conduct an autopsy. Surprise surprise, this time they came to a different conclusion.

“We have established beyond a doubt that Mrs. Stanford died a natural death,” Jordan announced. Jane had pre-existing conditions, he claimed. Oh, and that lovely picnic she enjoyed? Turns out, she had gorged herself on food and sweets, exacerbating her issues and leading to her death. This claim was backed by Berner, whose account of the picnic’s menu became increasingly gluttonous over the years.

As for why other servants who witnessed Jane’s grisly death were backing the poisoning verdict, Jordan claimed they were involved in an effort to discredit one of their own—Jane’s private secretary, Berner—who had worked for their boss for over two decades and was set to receive a small but life-changing inheritance.

The affair of the mysterious death of Jane Stanford wasn’t so much resolved as disappeared. The investigation was moved to San Francisco, where the lead investigator, who had his eye on the chief of police position, was more than happy to “find” zero evidence for murder at the request of the DA who had close ties to Jordan. In the years that followed, thanks to earthquakes, fires, and some probable bad behavior, a lot of the Stanford family records and records of the investigation were destroyed.

Stanford University Campus.

David Butow/Corbis via Getty ImagesFor 100 years, that was that. While whispers may have lingered, Jane’s death was a successful cover-up with all the powers that be accepting that the issue had been resolved and no crime had occurred.

But those whispers never dimmed and in 2003, the issue was taken back up again by a retired Stanford doctor. Robert W.P. Cutler examined all of the evidence he could get his hands on, and much still remained despite the destruction, and published his conclusions in The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford. He stated almost definitively that Jane was murdered.

This was the first spark and what would be a series of investigations over the next two decades, work which has led to what will most likely be the most final conclusion that this episode will ever get.

The accusation in this game of Clue: Miss Jane Stanford was murdered in her hotel room with strychnine supplied by Jordan and administered by Berner to ensure that there were no disputes to her will and to secure her fortune for Stanford University.

As White, the latest in the Stanford historical investigators, concluded, “I was able to narrow it down to who had the motive and opportunity to poison her twice. There are plenty of legitimate suspects, but I’m pretty satisfied.”