Republicans move from one culture war to the next, like Tarzan swinging through the trees. It can be hard to keep up with the nonsense, but try we must.

After last year’s all-out assault on transgender children, pregnant women, the accurate teaching of history, and books—the right has expanded its roster to include some new issues.

This includes efforts to repeal no-fault divorce laws, which are now popping up in red spots around the country. The Republican Party of Texas, for example, adopted a (disturbing) platform in 2022 that includes this plank: “214. No-Fault Divorce: We urge the Legislature to rescind unilateral no-fault divorce laws…”

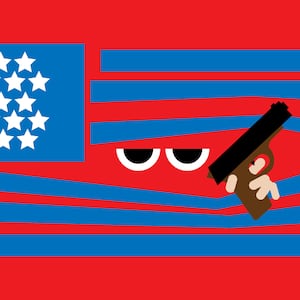

Compared with some of the other planks, which do things like declare the 2020 presidential election illegitimate, call for the elimination of any gun-free zone in Texas, and urge the prohibition of sex education in schools, this one might seem relatively harmless. Maybe even sensible. But even a rudimentary understanding of family law and its history reveals why this would be a terrible idea.

Conservative commentators are joining the calls to end no-fault divorce. Steven Crowder bemoaned the fact that Texas law permitted his wife to divorce him just because “she didn’t want to be married anymore.”

There is nothing special about Texas in this regard—every state has at least one no-fault ground for divorce. And he’s right when he says that a person can file for divorce because they no longer want to be married to their spouse. This is the product of the no-fault revolution that began in 1970, and during which every single state either eliminated fault-based divorce or added a no-fault ground.

The earliest divorce laws in this country required the party seeking divorce to prove that the other party had committed one of the enumerated types of marital “fault” that the legislature had deemed sufficient to justify allowing the marriage to be dissolved. Every divorce law included adultery as a ground, and some states also had grounds like abandonment, neglect, imprisonment, or extreme cruelty. These grounds represented the legislature’s determination about what types of marital breakdown were dealbreakers.

But the fault-based system had other features, as well. The party filing for divorce had to be “innocent” of marital fault themselves—if each party proved the other had committed marital fault, the law said that the parties had to stay married under the doctrine of recrimination.

In other words, the worse the marriage, the longer it should last.

The law also did not permit default judgments of divorce, so even if the defendant did not contest the divorce or make any appearance at all before the court, the plaintiff still had to provide proof that the fault occurred and that it met the standard set out in the statute. And if a judge suspected the parties were colluding to contrive fault, that divorce had to be denied, as well.

The fault-based system was deliberately stingy with divorce.

State legislatures by and large thought people should stay married until “death do them part.” But people did not want to be stuck in marriages against their will.

The demand for divorce began to rise in the second half of the nineteenth century and rose steadily. Though an uninformed, history-hating Texas Republican legislator may attribute this trend to the devaluing of marriage, the opposite is true. Changing social realities meant that people wanted more out of marriage—and were therefore more likely to be disappointed by its realities.

The shift from a transactional view of marriage, to a companionate one, meant that spouses placed more of a premium on the emotional and sexual aspects of marriage rather than the exchange of breadwinning for housekeeping. Marriage shifted again in the second half of the twentieth century as many people also wanted room within marriage for individual fulfillment—so-called “expressive marriage.”

The clash between the strict fault-based divorce laws and the rising demand for greater control over this essential aspect of people’s lives led to a total breakdown of the system.

Steven Crowder speaking at the 2013 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in National Harbor, Maryland.

Gage Skidmore/Gage SkidmoreIn the century preceding the no-fault revolution, divorce rates rose steadily even though the law didn’t change at all. Spouses colluded—one party would agree to be accused of fault and wouldn’t participate in the legal proceeding at all—and judges just looked the other way. So did lawyers, and bailiffs, and court reporters, who would hear identical testimony in case after case about affairs or beatings that did not really happen—or at least not in the way they were described.

The testimony curiously lined up perfectly with the language in the divorce statutes in every case. And when only one party wanted a divorce, that party fabricated evidence and perjured themselves to prove fault. The entire system was rancid and undermined faith in the rule of law. And for people who weren’t willing to lie, cheat, and steal to get out of their unsatisfying (or worse) marriages, they were just stuck.

The no-fault revolution had nothing to do with devaluing marriage or stomping on traditional family values. It had everything to do with devising a system that would be able to better distinguish between marriages that could be saved and marriages that could not—and in the latter case, to let people go.

A “no-fault” divorce law uses either a period of separation or a finding of “irreconcilable differences” to determine when a marriage should be dissolved, rather than an artificial focus on one particular incident. It also spares the parties and the court from conducting an autopsy of the marriage in open court and allows divorcing couples to focus their time, energy, and resources on sorting out finances and children.

Yes, no-fault divorce laws make it more likely that the Steven Crowders of the world might find themselves divorced against their will, but, honestly, that’s a good thing.

Maybe instead of berating his pregnant wife, he should have tried harder to be the husband she wanted and needed. And maybe instead of starting random fights about things they don’t understand, Republican legislatures should try harder to address actual problems plaguing our society and its inhabitants. No-fault divorce isn’t one of them.