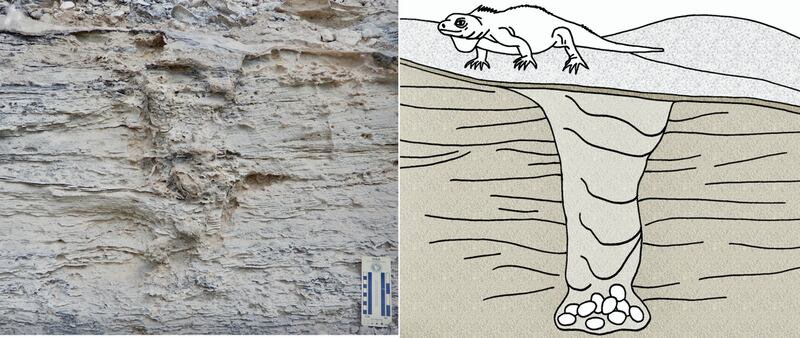

A pregnant iguana dug into a vegetated sand dune about 115,000 years ago on a small island in a chain of islands that one day would be called the Bahamas. Once she buried herself and was surrounded by loose sand, she scraped out a chamber and laid her eggs in it. On her way out of this underground nursery, she packed sand behind her, forming distinctive layers that marked her progress to the surface.

Once back in the sunshine, she tamped down the top to conceal the nest. Over many centuries, a thin layer of soil developed over the former nesting burrow, and minerals from that soil formed between the sand grains, turning the dune into limestone, which preserved the structure of the nesting burrow.

In December 2013, while exploring a roadcut on San Salvador Island in the Bahamas with 19 undergraduate geology students from Emory University, one of us (Anthony) noticed this unusual structure in the rock. It turns out the road excavators had unwittingly exposed a section of ancient sand dune, containing this iguana burrow from long ago.

An iguana from long ago carefully constructed this nest layer by layer.

Anthony J. Martin, CC BY-SAOver the next six years, with contributions from undergraduates and the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, we were able to conclude that we’d found not only the first known fossil iguana nesting burrow, but also the first trace fossil attributed to an iguana. Based on its geologic setting, we estimate the burrow is about 115,000 years old, placing it in the Late Pleistocene Epoch, which is best known for its ice ages and megafauna, like mammoths and giant ground sloths.

A trace fossil is indirect evidence of ancient life made while an organism was alive. The study of this iguana burrow and other trace fossils, such as tracks, nests, tooth impressions and feces, fall under the science of ichnology.

Trace fossils are important because they directly reflect ancient behavior. Also, unlike bones or shells, which are often moved after an animal’s death, most trace fossils are found exactly where they were created.

Trace fossils offer a unique window to the distant past. When a dinosaur sat down alongside a lake shore in modern-day Utah during the Early Jurassic Period about 200 million years ago, adjusted its stance, stood and walked away, that dinosaur’s behavior was recorded in the sediment beneath it. Similarly, when a fish swam along a lake bottom in modern-day Wyoming more than 50 million years ago, it left not only trails from its fins, but also impressions from its mouth along the lake bottom while feeding. And human footprints from about 12,000 years ago in modern-day New Mexico told of a young adult carrying a child across a foot path shared with mammoths and ground sloths.

Trace fossils, unlike shells and bones, provide snapshots—or even short documentary films—of animals living in their original environments.

Even though we found no body parts or eggs, there is ample evidence the structure we discovered in the Bahamas was an iguana burrow. The wind-blown layers in the former sand dune were clearly interrupted and mixed, showing the structure was made while the sand was still soft. It matches the width, depth and shape of modern iguana nesting burrows. And nearby, one of us (Melissa) found a fossilized land-crab burrow, insect burrows and root traces preserved in the outcrop, showing it was indeed an inland dune—exactly where an iguana would make a nest.

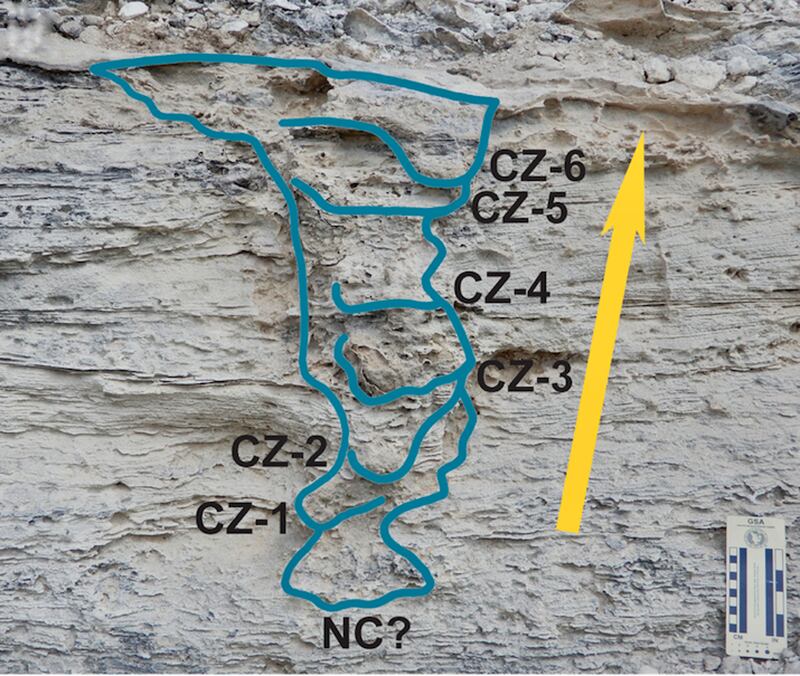

The most convincing clue, however, is the series of compacted sand layers inside the structure. These are the places where the expectant mother packed sand with her legs and head on her way out in order to conceal her eggs and hatchlings from predators.

Interestingly, we did not find any evidence that the hatchlings dug their way out, through the layers, to the surface—as iguana hatchlings do. This indicates a failed nest. Although hatching success in modern iguanas is normally high, nest failures happen, and are most likely when soil moisture is too high, such as after a heavy rain.

The burrow deconstructed into its behavioral parts. NC? is a trace of the possible nest chamber, CZ (1-6) shows the compaction zones, where the mother iguana packed sand behind her on her way out, and the arrow shows her overall direction of movement while exiting.

Anthony J. Martin, CC BY-SAThe oldest known iguana body fossils from San Salvador date from less than 12,000 years ago. The discovery of this burrow, from 115,000 years ago, greatly extends the natural history of iguanas in this location.

The iguanas that live on San Salvador Island today are among the rarest lizard species in the world—the San Salvador Island rock iguana (Cyclura riyeli riyeli). This species and others were common throughout the Bahamas before 1492, when Europeans introduced rats, pigs and other invasive species that preyed on eggs and iguanas of all ages. Now, fewer than 500 individuals persist on isolated cays offshore from the main part of San Salvador.

We hope our study generates awareness and appreciation of Bahamian iguanas and their long history in this area. We also hope it inspires their continued protection.

Anthony J. Martin is a professor of practice at Emory University and Melissa Hage is an assistant professor of environmental science at Emory.