Multimillionaire Dave McCormick put more than $14 million of his own money into his failed 2022 Senate campaign. But as he mounts a 2024 comeback, new disclosures this week reveal that, despite his enormous personal investment, his 2022 campaign still overspent money that his donors had contributed—in violation of federal law.

This time around—months before Donald Trump blessed him with an endorsement—McCormick was already under scrutiny for financing what legal experts said appeared to be a shadow campaign ahead of his 2024 revenge run.

That effort was peculiar because McCormick had kept his old 2022 campaign alive the whole time, even though he lost that primary to fellow non-Pennsylvanian Dr. Mehmet Oz.

But now, McCormick is raising new money from new donors not just to fund his 2024 bid, but—oddly enough—for his old 2022 campaign as well. And according to new Federal Election Commission filings, he’s also just now getting around to repaying a number of those 2022 donors, whose money his old campaign appears to have spent in the meantime, likely in violation of federal law.

This arrangement is all the more peculiar, because McCormick—a former hedge fund executive with a personal net worth well into the hundreds of millions—isn’t exactly strapped for cash. In fact, he contributed more than $14 million to his 2022 campaign and still overspent his donors’ money. (He’s self-funded about $2 million of the $11 million raised for 2024.)

Additionally, McCormick’s 2022 campaign has still not paid down hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt to a political firm run by prominent Republican consultant Jeff Roe. That debt—more than $336,000, according to filings submitted on Monday—has been on the books for nearly two years now.

Incredibly, thanks to that old debt, McCormick is currently raising money for his old campaign alongside his new campaign—and he’s even using the same joint fundraising committee to do so. (George W. Bush contributed $6,600 to that committee on March 31, listing his occupation as “former president.”)

A McCormick spokesperson did not respond to The Daily Beast’s comment request.

Jordan Libowitz, communications director for watchdog Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, told The Daily Beast that McCormick’s campaign appears to have broken one of the few clearly defined fundraising laws.

“There are very few hard rules, and this is one of them,” Libowitz said.

He explained that when candidates run in a primary, any money that they raise for the general election is segregated into a separate account. In 2022, The Daily Beast reported that the campaign for then-Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R-NC) had broken the same law while hemorrhaging cash during his doomed re-election primary.

Brendan Fischer, a campaign finance lawyer and deputy director of Documented, said that not only are general election funds off-limits, candidates must hold enough cash to refund all general contributions if they lose the primary.

“Basically, a candidate must carefully separate contributions for the primary from those for the general, and be prepared to refund the general election contributions within 60 days of losing the primary,” Fischer told The Daily Beast.

According to FEC filings submitted on Monday, on the last day of March this year McCormick’s old campaign refunded about $75,000 to donors who had contributed to his 2022 bid. Most of that money—$49,613.29—was marked as having been donated for the 2022 general, where McCormick was not a candidate. However, by the end of 2022, McCormick’s campaign only had $7,800 on hand. That math appears to mean the campaign spent more than $40,000 of donor funds that it was not allowed to touch in the first place.

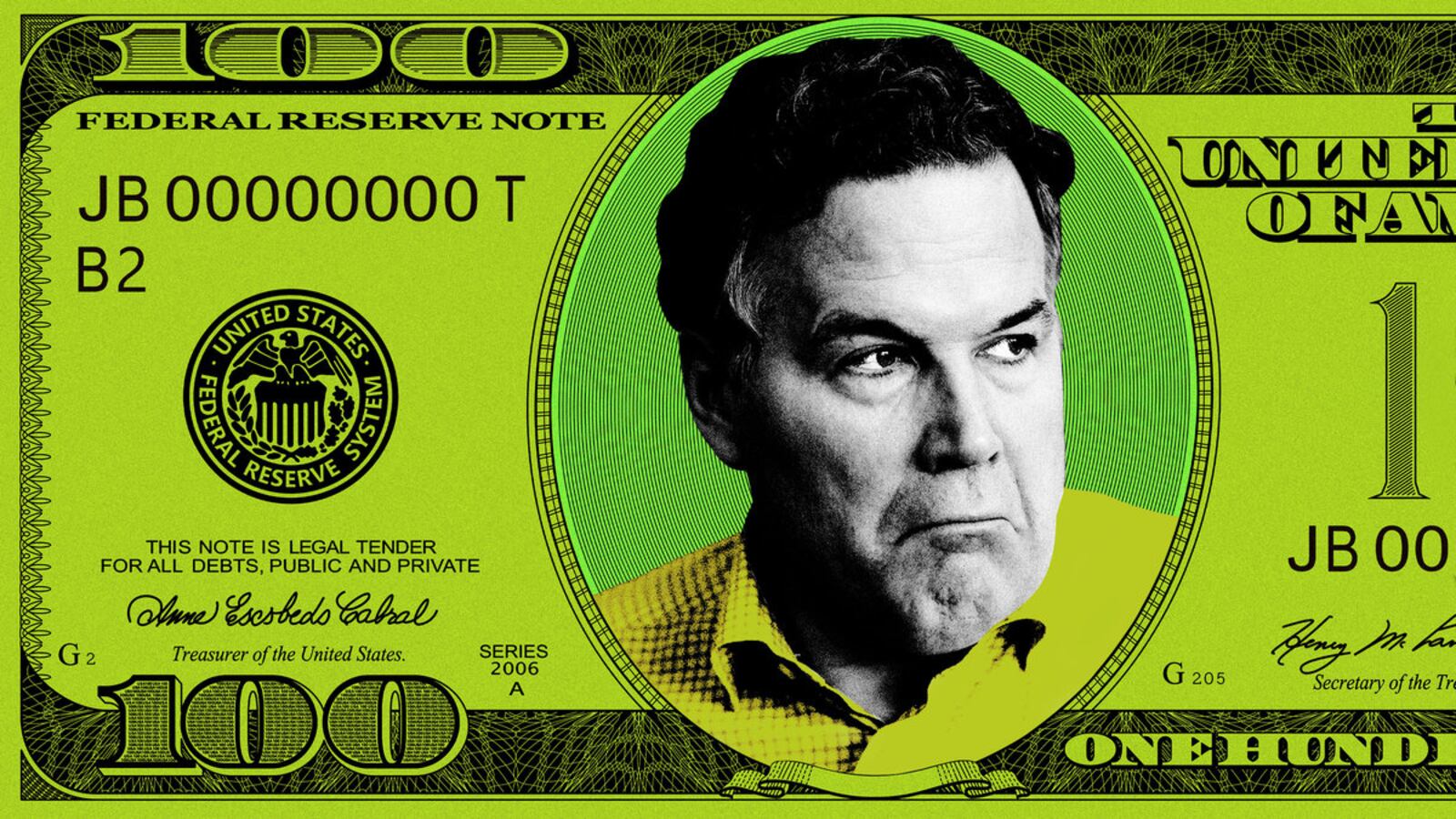

Pennsylvania Republican Senate candidate Dave McCormick greets supporters at the Indigo Hotel.

Photo by Jeff Swensen/Getty Images“I don’t understand how you can do that without having spent general funds. You can’t touch that to begin with. And it’s an easy refund—you typically pay that back right away,” Libowitz said, noting that, for more than two years, the campaign didn’t raise a dollar. “Then, you take what’s left from your primary account and pay off the vendors you owe.”

That entire time, however, the McCormick campaign was simultaneously carrying hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt owed to Axiom Strategies, Roe’s firm—debt that it still has not paid down.

Campaign committees are only allowed to raise money from donors after losing an election if they’re still carrying debt and the funds are marked for “debt retirement.” This January, more than a year after it raised its last dollar, the McCormick 2022 campaign began collecting new donations again—some of it in transfers from an affiliated joint committee that had received the donations as early as October of last year.

All those new contributions are for the maximum amount, and marked for “debt retirement,” FEC filings show. They include prominent names, like the Winklevoss twins of Social Network fame and the owner of Sheetz gas stations. They also include some less savory connections, including three magnates accused of sexual impropriety: disgraced casino magnate Steve Wynn, and not one but two of the businessmen swept up in a 2019 Florida massage parlor prostitution scandal—New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft, and investor John Childs, who both spread tens of thousands of dollars across multiple McCormick committees.

In 2022, when Trump opted for Dr. Oz in the primary, the former president called McCormick “the candidate of special interests and globalists and the Washington establishment.”

This time, however, Trump—who finally endorsed McCormick on Sunday—doesn’t have other options. McCormick is running unopposed in next week’s Republican primary, preparing to take on Democratic Sen. Bob Casey in the general. Both campaigns have already spent millions and still have plenty of cash on hand, though Casey’s war chest dwarfs McCormick’s, $11.9 million to $6.2 million.

“I suspect he’s doing this to double-dip from rich donors,” Libowitz said of McCormick’s joint fundraising arrangement with his old campaign, noting that each additional member committee allows the joint vehicle to increase its individual donor maximum.

Fischer said the donations might have another level of strategy.

“Once those 2022 donors are refunded, many will likely give another max-out donation to his 2024 campaign,” Fischer pointed out. But, like Libowitz, Fischer noted that, this entire time, McCormick “could’ve just put more of his own money into his campaign to refund those 2022 donors.”

Still, while the McCormick campaign was refunding those long-overdue 2022 donors, it did not put a dollar towards its debts to Roe. That roughly $336,000 debt is exactly the same today as it was in the campaign’s previous filing.

“I certainly haven’t seen something like this before,” Libowitz said, adding that if McCormick is just keeping Roe’s debt on the books in order to repay donors whose money he’s already spent, “that would be another major issue.”

Technically, the multimillionaire McCormick may have footed the refunds himself. Five days before the campaign refunded its old donors, McCormick personally contributed $78,713.29, exactly $3,700 more than the total refunds.

It’s not clear why McCormick didn’t do this earlier. In September 2022, for instance—four months after losing the primary—he loaned his campaign more than $670,000. But by the end of the month, the campaign still only had around $15,000 in the bank, according to filings from the time. In all, McCormick sunk nearly $14.4 million into that failed bid, and he hasn’t repaid himself a dollar.

But while McCormick’s general election donors were out of their money, he was setting up another political action committee. That committee, a state-level PAC in Pennsylvania, called “Pennsylvania Rising,” raised more than a million dollars last year—juiced by a $1 million gift from the state’s wealthiest resident, GOP megadonor Jeffrey Yass.

In October, The Daily Beast reported that Pennsylvania Rising’s spending, together with public reports documenting McCormick’s political moves at the time, bore the hallmarks of a “shadow campaign.” That fact pattern—including significant overlap with McCormick’s 2022 campaign in staff and consulting payments—led legal experts to raise questions about whether McCormick was using the state PAC to underwrite campaign activity while evading the federal ban on soft money.

But that PAC, it turns out, is still spending money—and now it’s demonstrating new overlap with McCormick’s Senate campaign. Both the state PAC and McCormick’s 2024 campaign have recently paid tens of thousands of dollars to a newly created private company. The shell company is obscuring the true recipient of travel expenses.

That new company, called “PA Travel LLC,” was registered with the Pennsylvania Department of State in December. Just two months later, Pennsylvania Rising reported paying the LLC $80,000 for travel, state filings show. However, it’s not clear exactly who the PAC could have been shuttling around the state—McCormick had already declared his federal candidacy, and the PAC did not report paying any staff over the same time period.

But that’s still a drop in the bucket compared to what McCormick’s new 2024 Senate campaign is also paying PA Travel LLC—a total $232,000, starting on Jan. 12. The state PAC paid the company two months later, on Feb. 9.

“You get into some tricky waters,” Libowitz said. “He’s already running. He shouldn’t be using the state PAC in that way.”

Libowitz added that an innocent explanation could involve McCormick simply finding a vendor he liked enough to use twice. But he added that the PA Travel LLC payments are “enough to raise some eyebrows,” noting two other details: the timing of its creation, and its direct connection to the McCormick campaign.

The LLC’s registered organizer is Zachary Wallen, an election law attorney at Chalmers, Adams, Backer & Kaufman. McCormick’s 2024 campaign has paid that firm nearly $60,000 for legal consulting, FEC records show, including more than $20,000 this year.

Those facts share parallels with another recent high-profile GOP candidate. Last year, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ doomed presidential campaign went in on a new private LLC with a powerful aligned super PAC after bruising reports about the funding behind his private jet travel, including payments to wealthy donors. The LLC, however, blocked the public from seeing who the campaign and super PAC were paying for flights.

That DeSantis super PAC, coincidentally, was also run by Jeff Roe.