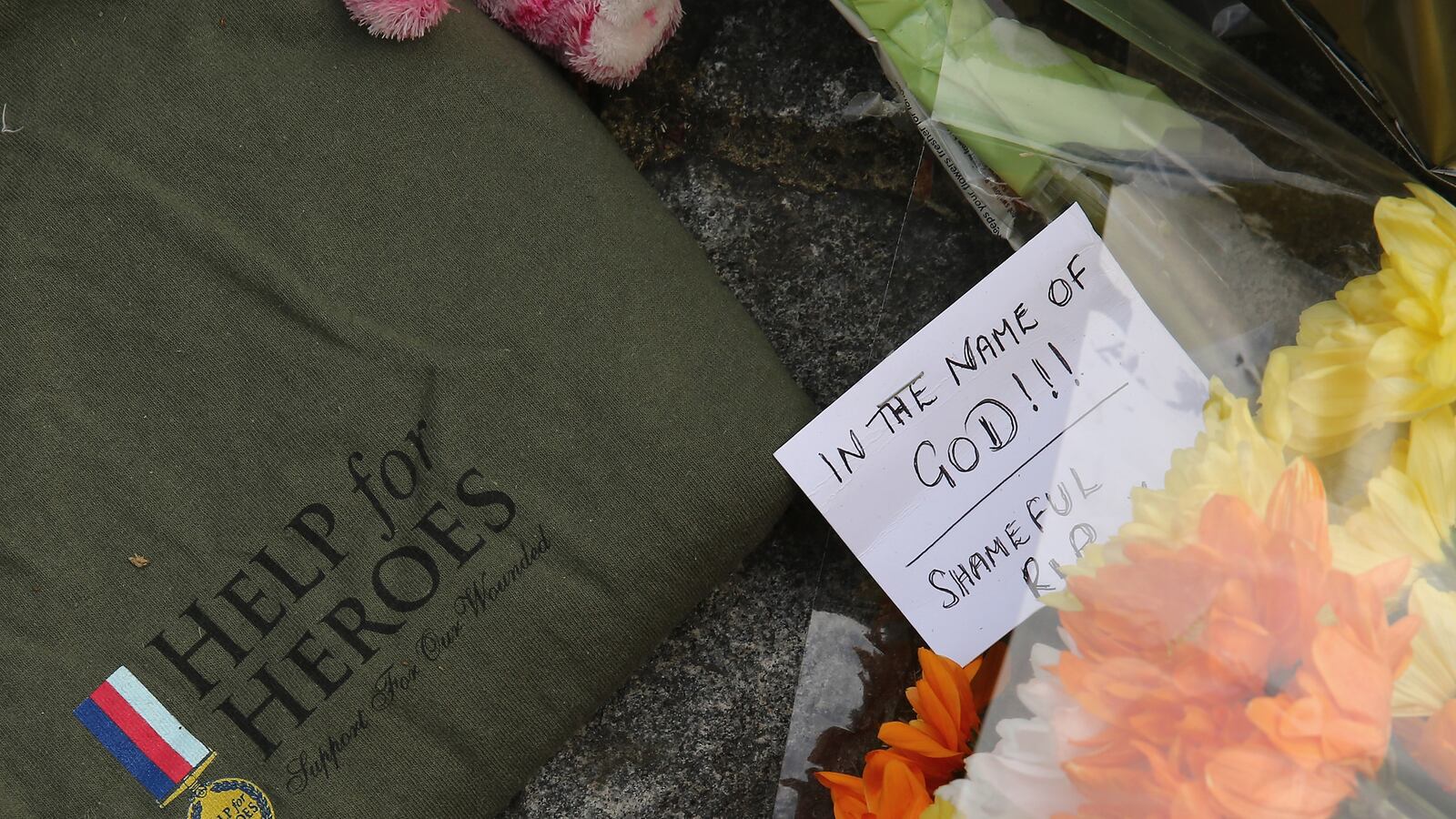

Yesterday at about 2:20 p.m., two young men armed with long knives and meat cleavers decapitated an off-duty soldier on an ordinary street in the London borough of Woolwich. The victim was wearing a “Help for Heroes” T-shirt, a charity to raise money for injured servicemen. The two attackers cried “Allahu Akhbar” as they hacked at him. Then, one of the attackers, still holding a bloodied machete and dripping knives, his hands still shining with fresh blood, still breathing hard from the work of separating a man’s head from his body, walked over to a TV camera and gave a monologue: “I apologize women had to see this, but in our country women have to see this every day.”

Our country? The British always place each other by their accents and this guy spoke pure Londonese, his body movements, intonations, even the way he said “I apologize” was so definitively English—only an English terrorist would say “sorry” while he murdered. If anything the young man sounded South London, maybe a Woolwich local. He said he wanted to start a “war.” If so, then Woolwich is the perfect place to start it.

Woolwich is a somewhat distant part of London. It’s almost impossible to get there, the last stop on the Docklands Railway. It’s traditionally a military area. When he was attacked, the victim had just exited the Royal Artillery Barracks. The barracks still look spectacular, with the longest Georgian façade in the country looking out over a square exactly modeled on the one in front of Buckingham Palace. Troops practice here before parading in front of the queen. This used to be home to the Princess of Wales regiment though most of the soldiers moved out along ago due to budgetary cutbacks.

When the supervising officer took me round the long corridors and wide stairs of the 19th-century barracks, they were empty. The burgundy carpet was faded. There were large plastic potted plants gathering dust. There was a once-grand dining room with mirrored walls and burnished chandeliers. It mainly gets rented out for corporate functions. In the gloomy drawing room were oil paintings of old generals and one of Princess Diana, painted in the 1980s. She had been portrayed in a modernist manner: her face all dabbed, violent brushstrokes, her eyes disturbed. “A lot of people don’t like that painting,” said the officer, “But we’re her regiment though there’s none of us left and she’s passed away.”

Down the hill from the barracks is the Royal Arsenal, which since the 16th century built the bombs and cannons and tanks which made Britain great. By 1914 it was the largest factory in Europe, a sprawling, secretive mini-city with tens of thousands of workers, its own railway and canal. The Arsenal was the main employer in Woolwich, but it was shut down after WWII when the Empire disappeared and the army shrunk. The Arsenal has been converted to “Manhattan style, loft apartments,” the vast majority still unsold. There’s a museum with Britain’s greatest collection of cannons and tanks—but Woolwich is so out of the way there are precious few visitors. The museum is run by volunteers with shaved heads and blazers. “We’re patriots,” they told me, “People accuse us of being members of the (neo-nationalist) English Defence League, but we just love our country.”

After the Arsenal was shut down Woolwich never recovered. This is now one of the poorest areas of London. Between the Arsenal and the Barracks is Woolwich town itself: mean Victorian dwellings and dull ‘60s blocks, betting shops (three in a row), pawn brokers, thrift stores, plucked chickens swinging in the open entrance to the H and S Halal Meat Market. Many buildings are boarded up and gutted, burnt down during the 2011 riots, which local councilors like to refer to delicately as “that unpleasantness.” Woolwich was one of the epicenters of the riots, CCTV footage broadcast across the country showed young men in hoods and balaclavas throwing missiles at retreating troops of policemen. It was the iconic image of the riots, but somehow the news got the location wrong and said the battles took place in Liverpool. Locals were upset. Woolwich is always ignored.

Last night, after the decapitation, rioters clashed with police again. This time the English Defence League marched through the center of Woolwich, called for revenge and waving Union Jacks. The police pushed them away. They were right to be nervous. The area is home to the most violent immigrant gangs in London, the Woolwich Boys, second-generation Somalis and Nigerians originally formed to defend themselves from attacks by skinheads but who have gone on to dominate the drugs trade.

The terrorist attack in Woolwich has inspired another round of hand-wringing about the breakdown of a coherent British narrative. It’s fast becoming the defining issue of the Cameron era. A maverick political party called the “United Kingdom Independence Party” has split the country and the Conservative party, threatening to bring gown the government while running on no policies apart from getting out of the E.U. and stopping immigration.

Meanwhile, the Scots are preparing for a referendum to quit Britain next year. Downing Street’s response has been to use every opportunity to wave the Union Jack (the Olympics, the Queen’s Jubilee) while studiously avoiding the more difficult question of what a 21st-century British identity might actually involve. As part of this patriotic PR, the area around Woolwich was awarded “Royal Status” last year, a symbolic but once-in-a-century event, a little like a part of town receiving a knighthood.

Union Jacks fluttered over the pawn shops and gutted houses. Schoolchildren thronged the pavement holding little flags. The highlight of the festivities was the return of a small part of the Royal Artillery to the barracks. Not the real, front-line soldiers, but the small part that does all the showy stuff during Royal parades, dressing in black 18th-century uniforms and setting off Waterloo-era cannons for the tourists. These troops are considered the finest horse riders in the country. They rode into the barracks, resplendent in their uniforms, right by the spot where the serviceman in the “Help for Heroes” T-shirt was decapitated yesterday.