When the Titanic sank in the early morning hours of April 15, 1912, survivors had to wait about two hours before the RMS Carpathia arrived in response to the doomed ship’s distress calls. During this time, they waited with just the hope that rescue would come—though while floating in the desolate and frigid waters of the North Atlantic, that was far from certain.

Rescuers did eventually arrive, taking the survivors on board and providing them with blankets, hot coffee, food, and medical aid. The crew of the Carpathia were later hailed as heroes and the captain, Arthur Rostron, was even knighted by King George V.

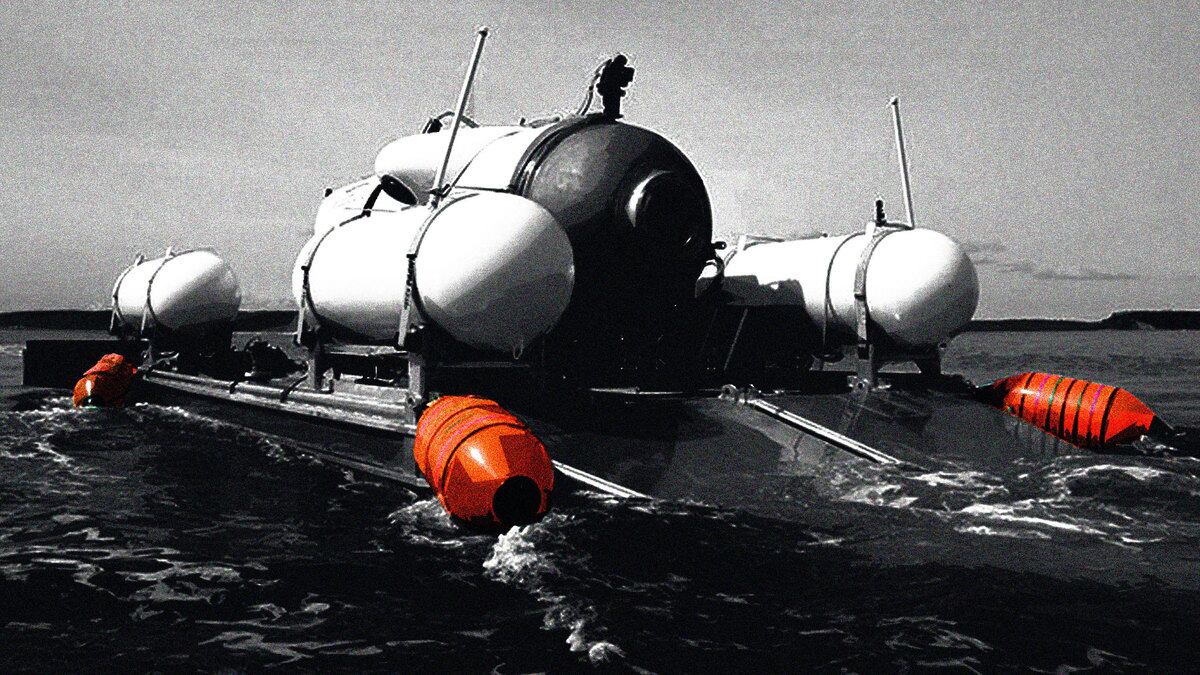

Today, the response to such a disaster would look much different—as we recently learned with the OceanGate tragedy that claimed the lives of five crew members aboard the Titan submersible. In the days following the Titan losing contact with its expedition vessel, an international effort of search and rescue teams mobilized in an attempt to find and save any of the potential survivors.

ADVERTISEMENT

The American and Canadian coast guards mobilized a fleet of ships, drones, and equipment hailing from several different countries to scour an area of the ocean roughly the size of Connecticut. This included two C-130 transport planes from the U.S. Army, two Canadian planes with sonar devices, several ships including a research vessel from the French government carrying an exploration robot, and a host of sonar probes to detect any sounds created by potential survivors.

While there have been plenty of rescues at sea since the sinking of the Titanic, there hadn’t been quite an undertaking like this one. The Titan was traveling to the depths of the wreckage 2.5 miles under the sea. The immense weight of the water pressure is 5,500 lbs per square inch. That’s roughly the equivalent of a tower of lead the size of the Empire State Building resting on your body. Not only did rescuers have to contend with an inhospitable and downright deadly environment—but they also had to leverage technology they don’t often use for sea rescues like remote-operated underwater vehicles (ROV).

“There is terrific robot technology already available for rescue but the robots are not available 24/7 in the right location,” Robin Murphy, the co-founder of the Center for Robot-Assisted Search and Rescue (CRASAR) and professor of computer science and engineering at Texas A&M, told The Daily Beast. “Disasters like this are fortunately rare, and like mine and nuclear disasters, it becomes a complex cost-benefit decision.”

Murphy explained that the rarity of such emergencies is a double-edged sword. While it’s great that responders don’t often have to save people from deep-water situations, it also means that both the systems and technology involved in saving them are unused, unpracticed, and unfamiliar.

Robotic technology undergoes frequent software and hardware updates too. That means when these situations do arrive, search and rescue teams might not have the correct equipment—and what they do have might be very out of date.

“You’d like to have the best technology, but if it never gets used, everyone gets rusty,” she said. “When they dust off the robot, it’s awkward, like trying to remember how to drive a car with a manual transmission when you’re used to automatic.”

These robotics aren’t necessarily made for the job either. Most ROVs are created for the purposes of scientific research and deep-sea mapping—not saving the lives of wayward tourists. They’re not optimized for search and rescue, so they might not have the necessary tools needed in order to best find the missing crew.

These types of robotics are also large and cumbersome. Likewise, transporting them is a slow and costly process. You can’t just airdrop them from a plane like the sonar sensors. They require an additional research vessel to transport and deploy it.

“Anytime you're operating at sea, everything sort of happens in slow motion,” David Strachan, an analyst at the naval warfare consulting firm Strikepod, told The Daily Beast. “When you're talking about having to deploy an ROV for a rescue operation like this, they're the size of a small car, or even a minivan in some cases.”

Strachan explained that the ROV requires a “fair amount of heavy-duty infrastructure in place” just to get into the water, including a winch, crane, and giant spools of cord to remain attached to the ROV as it travels downward. “That umbilical enables it to be controlled by the pilot in the ship,” he said. “So often, it’s just already fully integrated into a ship.”

Moreover, what happened in the case of the Titan is incredibly novel. Perhaps one of the closest comparisons would be the U.S. Navy’s 2022 recovery of an F-18 fighter jet that had blown off of its aircraft carrier and into the sea—where it plummeted nearly 2 miles to the ocean floor. For that, the team drew on a specially created ROV called the Cable-controlled Undersea Recovery Vehicle (CURV) in order to salvage the wreck. It still took the military a month to recover the craft.

With the Titan, it was a race against the clock for search and rescue—which meant trying to get all the resources like ROVs. “These types of disasters are rare, so rapidly diverting the best robots in the world from the ‘day jobs’ to the disaster is probably the best, most practical strategy,” Murphy said.

While this disaster does show how under-resourced most emergency operations can be with deep-sea rescues, it doesn’t necessarily mean that countries and militaries should start investing in armies of underwater rescue drones. Remember: These types of disasters are rare and practically never happen. In the more than fifty years since the first deep-sea exploration, such a catastrophe has “never happened” before the Titan, Robert Ballard, the deep-sea explorer who discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985, told ABC. “It’s safer to be in a submarine [...] than driving on I-95.”

What’s more important is having sound safety practices and regulations in place. This, above all else, should be one of the biggest lessons learned when it comes to the tragic saga of the Titan—especially after facts about how OceanGate has a controversial history with bucking safety protocol.

“An ounce of prevention equals a pound of cure,” Strachan said. “We won't know for some time, if ever, what the exact cause of implosion was, but I think it's safe to assume that faulty or unsafe construction was a contributing factor.”

Strachan added that, while it was ultimately futile, the quick and robust response from search and rescue operators was admirable and gave faster closure to a tragic event.

“The fact that they were able to find a debris field from a small submersible in such a relatively short period of time is a testament to the effectiveness of the marine technologies involved, the skill of the ROV operators, and the seamanship of ship handlers,” he said. “Had the Titan been stranded on the seabed or in the water column, with enough breathable air for the crew, there may very well have been a different outcome.”

Perhaps, if there is any bright light to the darkness of these events, it’s just that. While much has changed since the days of the Titanic, we can always rest assured that when things do go wrong at sea, people—for the most part—are more than willing to band together to help the victims in any way they can, whether it be through blankets, a hot cup of coffee, or a robot drone.