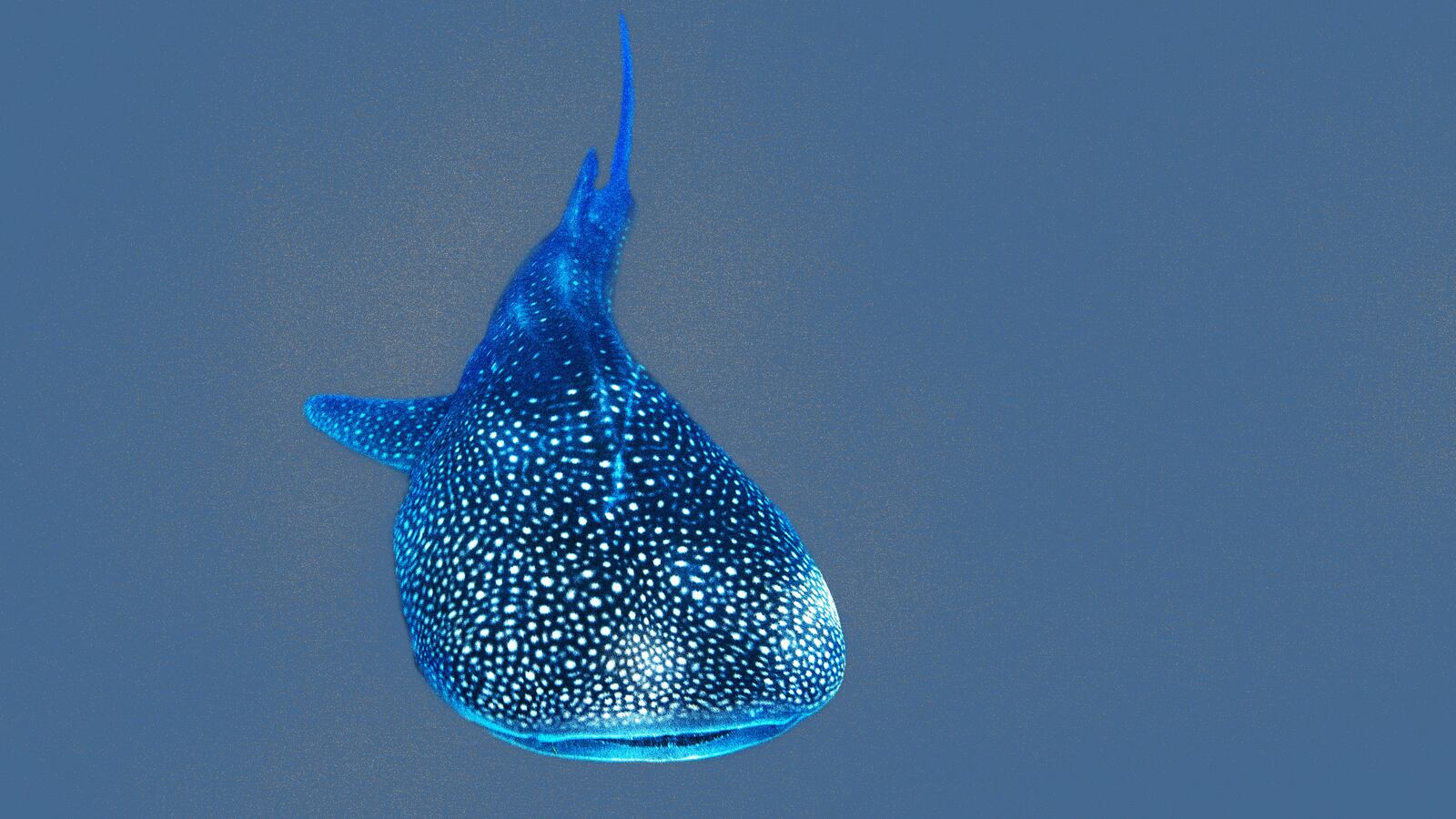

The small (compared to the rest of it), beady eye of the largest living fish in the ocean is just a few meters away from my face as it swims past, barely noticing my presence—I’m dwarfed by this mammoth juvenile’s five meters. That’s right, this mega shark isn’t even fully grown. As an adult, it could reach up to 20 meters.

I keep my distance, although not for the reasons you might think. This endangered whale shark (Rhincodon typus) might have hundreds of tiny teeth, but it definitely doesn’t use them to bite snorkelers like me. This placid plankton-eater is harmless to humans and actually pretty endearing (think clumsy Destiny the whale shark in Finding Dory).

As I swim alongside the gigantic shark, I’m trying to take a photo identification of the unique, stellar dot patterns scattered across its back. Like a human fingerprint, these patterns can help researchers tell which individual they’ve seen in the water. This information is crucial to learning more about the movements and populations of these enigmatic creatures, so we can better protect their habitats. Getting too close could disturb or frighten the shark, so I’m careful to stay around four meters away, giving it plenty of space.

We haven’t been back in the boat for long before another huge shadow passes below us—this time a giant manta ray (Mobula birostris), the largest type of ray in the world. I slide into the water quietly and watch as the manta performs an elegant ballet: tumbling and rolling below me. The ID photo (for the manta it’s the distinctive pattern on its belly) is going to be hard to take with it moving so fast.

But how did I get here, in the Indian Ocean with graceful manta rays dancing beside me? For the past eight months I’ve been volunteering with the Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF), helping them in their mission to protect our ocean. While I’m not a trained scientist, I’ve always been passionate about ocean conservation and when the opportunity to came up to help MMF with their work in Mozambique, I jumped at the chance. While largely based in the office looking after communications and social media, I was lucky enough to be able to join scuba diving and snorkeling boats on weekends for incredible encounters like this.

Mozambique has one of Africa’s longest, most biodiverse coastlines. Tofo Beach in the Inhambane province is a particularly special place for marine biodiversity. It’s one of the few places on the planet where whale sharks and manta rays can be found year round. It’s home to turtles, bottlenose dolphins, humpback dolphins, and the rare smalleye stingray. During the winter months (June to October), humpback whales travel north to breed before returning with their calves to rest and teach their calves to breach in the protection of Tofo bay and continue south to feed in colder waters.

But why is Tofo such an irresistible magnet for these ocean giants? It’s all down to its unique location. The Mozambique Channel, which lies between mainland Africa and Madagascar, is heavily influenced by cyclonic and anti-cyclonic current eddies that draw cold, nutrient-rich water up from the deep, creating upwellings close to shore. This enables lots of zooplankton (aka “fish food” for our filter-feeding ocean giants) to bloom.

During these plankton blooms, the ocean serves up a veritable buffet of delicacies to attract hungry whale sharks and manta rays. Because their food is so small, mantas and whale sharks have to feed in areas where there’s an abundance of zooplankton, so these blooms are really important. In most other locations where these megafauna are found, the blooms only occur for a couple of months of the year. But the current eddies in Tofo ensure that plankton is is always plentiful for these enormous animals to hoover up whenever they’re hungry, no matter what time of year. What’s more, the fact that this phenomenon takes place so close to shore makes it easy for divers and snorkelers to hop into the water and swim with them.

The brutal Mozambican civil war, which ravaged the country from 1977 to 1992, also helped protect this precious piece of coastline by keeping this ocean paradise out of reach of the rest of the world. When marine biologist Dr. Andrea Marshall arrived in the country in 2003 to do some exploratory diving, what she saw under the waves blew her away—so much so that 15 years later, she’s still based in Mozambique and has dedicated her life to studying the beguiling manta ray so abundant in the region.

When Marshall arrived, there was so little information available about manta rays that she and a team of experts led an assessment that ultimately earned the rays a “data deficient” rating on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species. A desire to solve this puzzle led her to further investigate this yet unexplored coastline and to become a leading authority on these graceful and enigmatic animals. In just eight years, Marshall and a group of scientists have been able to collect enough evidence to determine that manta rays are vulnerable to extinction. This move was instrumental to their protection because it resulted in manta rays being listed on two of the world’s most important conservation treaties: the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). Once Marshall fell for mantas, it became a lifelong love and she’s now so well known for her work into manta ray conservation that she’s affectionately called the “Queen of Mantas.”.

In 2005 her friend and colleague, Dr. Simon Pierce, joined her In Mozambique, hoping to learn more about the large populations of whale sharks being seen in the same area. Captivated by these gentle giants, he stayed on to conduct further research into the conservation of these gentle sharks and has become one of the leading experts on the species.

Together, Marshall and Pierce founded the MMF in 2009 to try to protect these ocean giants from threats such as fisheries, boat strikes, ocean pollution and being accidentally caught in fishing nets. A sevenfold increase in gill net fishing along the Mozambican coastline has coincided with sharp declines in whale shark and manta ray sightings.

So, what can be done to protect these endangered (whale sharks) and vulnerable (manta rays) animals from becoming extinct? The charity is working hard to find out more about these mysterious creatures and use that knowledge to inform global conservation strategies. On a local level, they’re working with Mozambican communities, trying to inspire them to fall in love with and learn to protect the ocean.

Tourism to the country could be a blessing or a curse, depending on how it’s managed. The country’s proximity to ocean giants and the possibilities of world-class diving experience is beginning to attract tourists to the region to see these majestic animals. Too many people flooding in could become unsustainable, particularly if codes of conduct for animal encounters aren’t upheld. However, if managed properly, tourism can be hugely beneficial to the conservation of these threatened species: raising awareness of important conservation issues and contributing to citizen science projects—where non-scientists can help contribute to the charity’s research, for example by submitting their own ID photos of marine animals they see while snorkelling or scuba diving—not to mention contributing to the estimated global annual value of whale shark ($100 million) and manta ray ($149 million) tourism. And once governments begin to calculate how much money they might lose if they lost the mantas and whale sharks, this could trigger more conservation legislation.

Until that time, the MMF team will be in the water trying to find out more about these amazing animals in the hope we can learn more about how best to protect them.