There are cult books, and then there are cult books. An example of the former might be John Williams’s novel Stoner, or John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. Books with a niche following that sometimes—like in the case of Catcher in the Rye or On the Road—explode to become part of the canon. The latter are books about cults, real or fictional. There is Lawrence Wright’s recent Scientology exposé, Going Clear. Charles Portis, the reclusive author of True Grit and The Dog of the South, has achieved the rare cult double; he’s a cult author who has written about a cult. His 1985 novel Masters of Atlantis concerns the plight of the Gnomons, a group dedicated to sharing the mysteries of Atlantis.

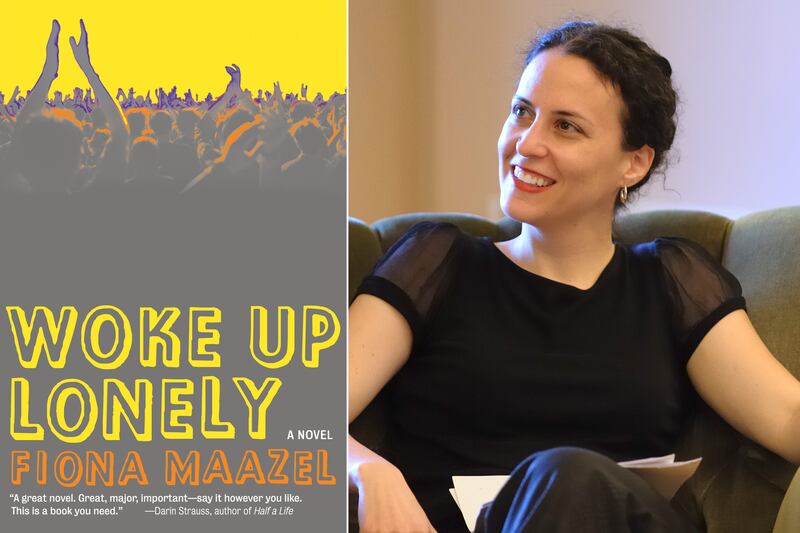

Fiona Maazel’s latest novel, Woke Up Lonely, might very well put her in Portis’s rarefied company. At the center of the book is the elusive Thurlow Dan, a charismatic L. Ron Hubbard type who runs the Helix, “a therapeutic community he’d banked to stardom,” with some 160,000 members. Dan also may or may not be conspiring with the North Korean government for the violent overthrow of the United States. Helix’s mission statement, though, is something less incendiary: it aims to cure modern society’s inherent loneliness by any means necessary.

In many ways, Dan is as simple as a child. Helix isn’t a Ponzi scheme, and Dan is not a writer of bad science fiction turned flim-flam artist. His video message to the world, filmed from inside his Cincinnati compound, isn’t exactly the stuff of a revolutionary firebrand. “This place is a clink,” Dan says.

Three stories, fifteen rooms, stone façade, lintels. A Renaissance revival in a corner of Ohio. See those windows? My head of security—his name is Dean—says they’re bulletproof, UV resistant, and self-tinting. I think my Murphy bed is some kind of escape vehicle. And at night, when I’m scrubbing my teeth with the electric toothbrush he gave me last month, I think it checks my vitals.

Still, Helix’s wild popularity and alleged ties with nuclear-powered rogue regimes has bumped it up to No. 1 on the American government’s shit list. Fortunately for Dan, the task force in charge of bringing him down is headed up by his estranged ex-wife, a master of disguise named Esme. Even though the pair hasn’t seen each other in years, they both still carry a torch, and Dan orchestrates a hostage crisis to win her back. “He thought about the hostages. The troops in the market. His wife and daughter and the life they had together, pillaged by a lonely guy who screwed up every chance he got.” Fortunately for him, the whole reason Esme has set herself up to lead the ongoing Helix investigation is so she can keep Dan from getting extradited to a CIA black site or worse.

Maazel’s previous novel, Last Last Chance, concerned itself with the challenges of kicking drug addiction amid the apocalypse. Even as the world crumbled around them, the addicts were only concerned about how the end of the world would upstage them and their efforts to get clean. The main actors in Woke Up Lonely, meanwhile, are fighting an even more desperate battle—to be together in a world where everyone is together at all times.

The idea that people are growing more alienated from one another, despite ever greater means of “connectivity,” is not a new one. Maazel, though, has a real talent for taking these existential millstones of modern life—fear of death, failure, being alone, everything—and filtering them into morbidly funny, troublingly familiar forms. Maazel writes about a soon-to-be Helix hostage, Anne-Janet, who was on “cancer furlough.” To make the best of her remaining time, she wanted to date “with minimal exposure to men, which explained her plans for the night. A Helix event. Speed dating.” Another of Thurlow Dan’s hostages is a failed filmmaker whose big ideas were deflated by terrible luck and a very pregnant wife. He only finds out about the baby after gambling away their savings in an effort to finance a documentary. “The day she got pregnant was etched in his mind as the most confusing of his life. The panic was incredible. The joy unbridled. The effort it took to hide the panic almost life threatening.” There are neuroses enough here aplenty, and only the seriously self-deluded would claim they don’t recognize any of them from personal experience.

These are extreme cases, but there’s a reason Helix is growing so quickly. It taps into some primal truth. The irony of Dan’s predicament is that he would destroy Helix without a second thought in order to be with his wife and daughter again. For all his prognostications instructing people to make human connections, he himself is no closer to an answer.

Critics ranging from Walter Benjamin to Roland Barthes to, most recently, Reality Hunger author David Shields, have long argued that the novel’s time has past—that it is no longer an adequate form to reflect the truths of modern life. (This conversation has been happening for nearly 100 years. It’s a slow death.) Still, these thinkers make fairly convincing arguments. But for all its madcap zaniness, Woke Up Lonely easily refutes the idea that the novel is a staid, obsolete form of writing. The stakes in Maazel’s book are at least as real as any work of nonfiction, and it’s a good deal more fun to read than any manifesto.