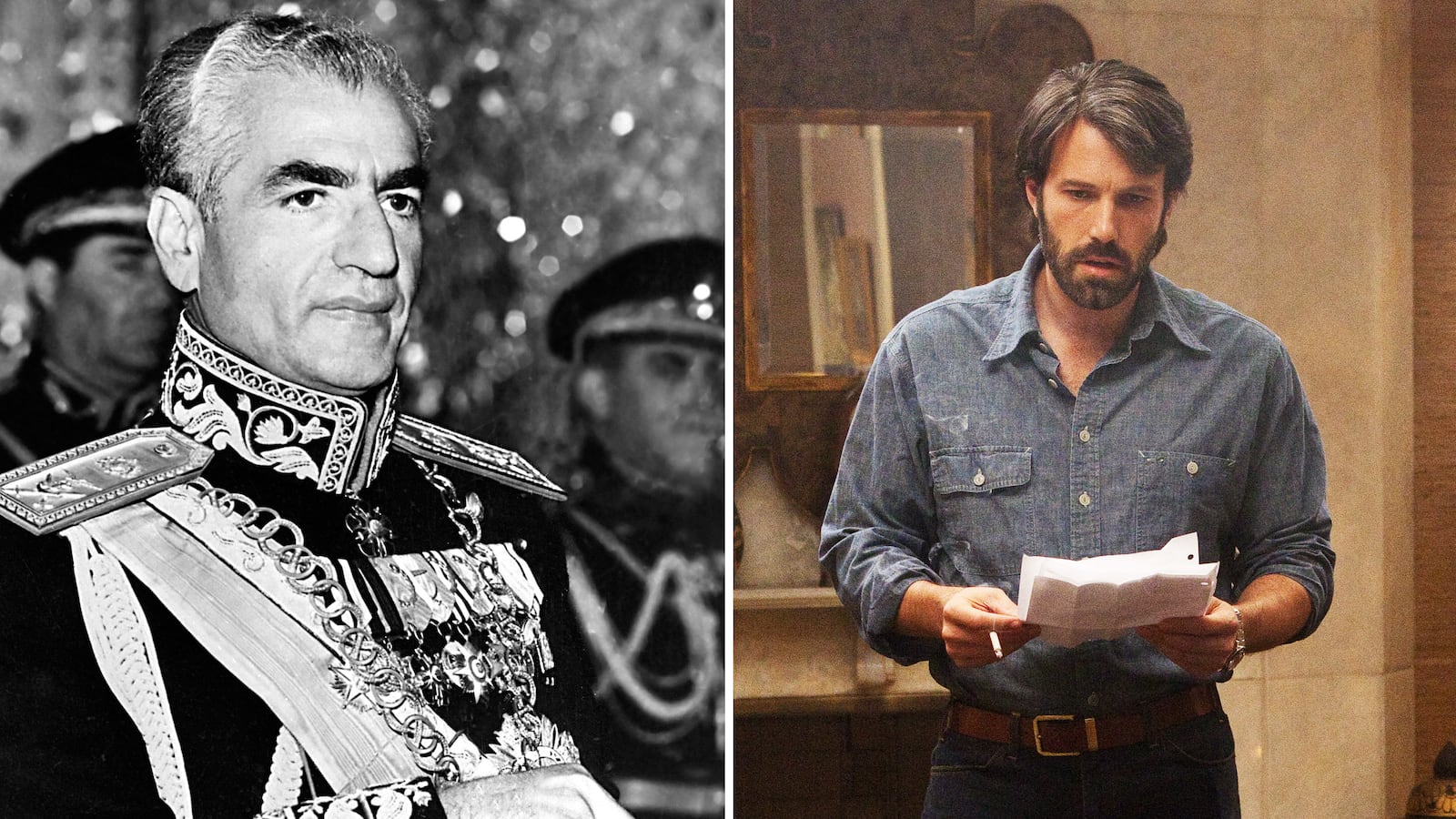

As we approach the 34th anniversary of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the commercial success of Ben Affleck’s film Argo is a timely reminder of the great tragedy that severed relations between Iran and the United States. During most of the 20th century these two great countries enjoyed generally cordial and constructive relations.

It is baffling that after 33 years of the Islamic Republic, with its dreadful record on human rights, abuses, and excesses, the director found it necessary to open Argo with a distorted and one-dimensional picture of life in Iran before the revolution. Understandably, Argo is not a documentary. But it is a motion picture which purports to re-enact true events about recent Iranian history. Affleck told Interview magazine that he went to special lengths to achieve historical accuracy, to the point where he considered traveling to Iran (he said he was dissuaded from making the trip by his studio and by the U.S. State Department). “I wanted to go—just for research—very badly,” he said. “I really wanted to be accurate.”

Yet very little about the first few minutes of Argo can be described as accurate. Over the years, the Pahlavi era has been hailed for its successes and criticized for its failings. Some criticisms are fair, others are not, just as some are truthful and others have no bearing whatsoever on reality. This is part of the natural process of trying to understand our collective experiences. All societies examine and reexamine their histories. We also understand that life on the public stage invites scrutiny. Nonetheless, Argo pushes the boundaries of fairness and truthfulness beyond what some would regard as acceptable norms even for a Hollywood movie.

The history of the Pahlavi era and pre-revolutionary Iran is presented in Argo from the vantage point of a series of cartoonish vignettes. The vignettes contain some surprising (and surprisingly basic) factual errors and inaccuracies:

• The film claims that in 1953 a democratically elected prime minister, Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh, was overthrown in a plot that installed the Shah on the Peacock Throne. In pre-revolutionary Iran, the prime minister was always appointed after receiving a vote of confidence from the Parliament. Dr. Mossadegh was appointed to his post by the Shah in 1951 and then again in 1952.

• The Shah did not become king in 1953—he had already been on the throne since 1941 (following the ouster of his father at the hands of the British and Russians).

• The accusation that the Shah was a “puppet” of the West and particularly the Americans is an old canard disproven by the most recent scholarship. To the contrary, the Shah was a strong nationalist whose ambitions led to protracted and intense disagreements between Tehran and Washington over the direction of Iran’s foreign and domestic policies.

• The Shah’s consort and widow, Queen Farah, did not bathe in milk. Moreover, the absurd statement that the Shah’s personal meals were flown to Iran by Concorde from Paris is pure fabrication. Does anyone seriously believe that the Shah of Iran was so bereft of a decent meal in a country renowned for its splendid cuisine that he actually imported his personal meals? The reality was very different. The Shah’s dietary habits—he was allergic to certain foodstuffs including caviar—and his natural modesty meant that he preferred simple local dishes.

Quite aside from Argo’s factual errors, there is the issue of how Affleck depicts the Iranian people. The Iranians who stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979 and held American diplomats hostage committed criminal acts. We, as Iranians, were then and will always be ashamed of what they did. We do not wish to be associated with these acts. Nor will we allow ourselves to be defined by what the Islamic Republic did in the years following the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty. Thirty-three million Iranians (Iran’s population in 1979) did not commit acts of murder and terrorism. Thirty-three million Iranians did not chant “Death to America!” or take Americans hostage.

The record shows that from a very early date many millions of Iranians were appalled at the excesses of the Khomeini regime and horrified by its violations of international and domestic law. The tragic reality is that many of the same Iranians who initially marched against the Shah and cheered when he left the country later bitterly regretted their earlier opposition. If they could turn the clock back, believe me they would. They understand that Iran during the Shah’s 37-year reign, whatever its blemishes, made enormous strides that today can barely be comprehended. They lament the massacre of innocents, the stoning of women, the blatant economic mismanagement and widespread corruption, the cruel fate of children ordered to walk through minefields to clear them of explosives during the Iran-Iraq war, and so many other abuses and excesses. They remember that their king refused to turn the army’s guns against his own people and that he left for exile rather than instigate a bloodbath.

Whatever the intentions of Argo’s director—and I do believe Affleck’s intentions were and are sincere—his film perpetuates the unfortunate contemporary stereotype that Iranians somehow “hate” Americans. Nothing could be further from the truth. American visitors to Iran bear witness to the fact that the Iranians they meet go to special lengths to receive them with hospitality. It is unfortunate that young Iranians feel they have to prove to foreign visitors that they are human too, and that like their American peers they share similar dreams of a better life and aspire to build a better world. Imagine what it must be like to start life from that point at that tender age—to feel that you have to somehow prove that you are not a hatemonger or an extremist? It is a burden that too many young Iranians carry with them.

Like many Iranians, I look forward to a time when we can look at the Shah’s reign and the tragic events of the revolution in a calmer, more reflective way. I think most fair-minded Iranians will appreciate that the director’s brief and absurd portrayal of the queen as some sort of Persian Cleopatra in no way diminishes her passionate advocacy in support of women’s and children’s rights, nor does it trivialize her ongoing efforts to champion Persian culture and the arts. Her life now, as then, remains dedicated to serving the welfare and wellbeing of the Iranian nation.

Affleck is certainly entitled to his viewpoint and artistic license. He presumably understands that there are risks involved in trying to interpret another country’s history and experiences. That does not mean he should not have made the film. To the contrary, artistry and entertainment offer invaluable forms of communication between cultures. Our concern is that this particular film sends the wrong sort of message to its intended audience.