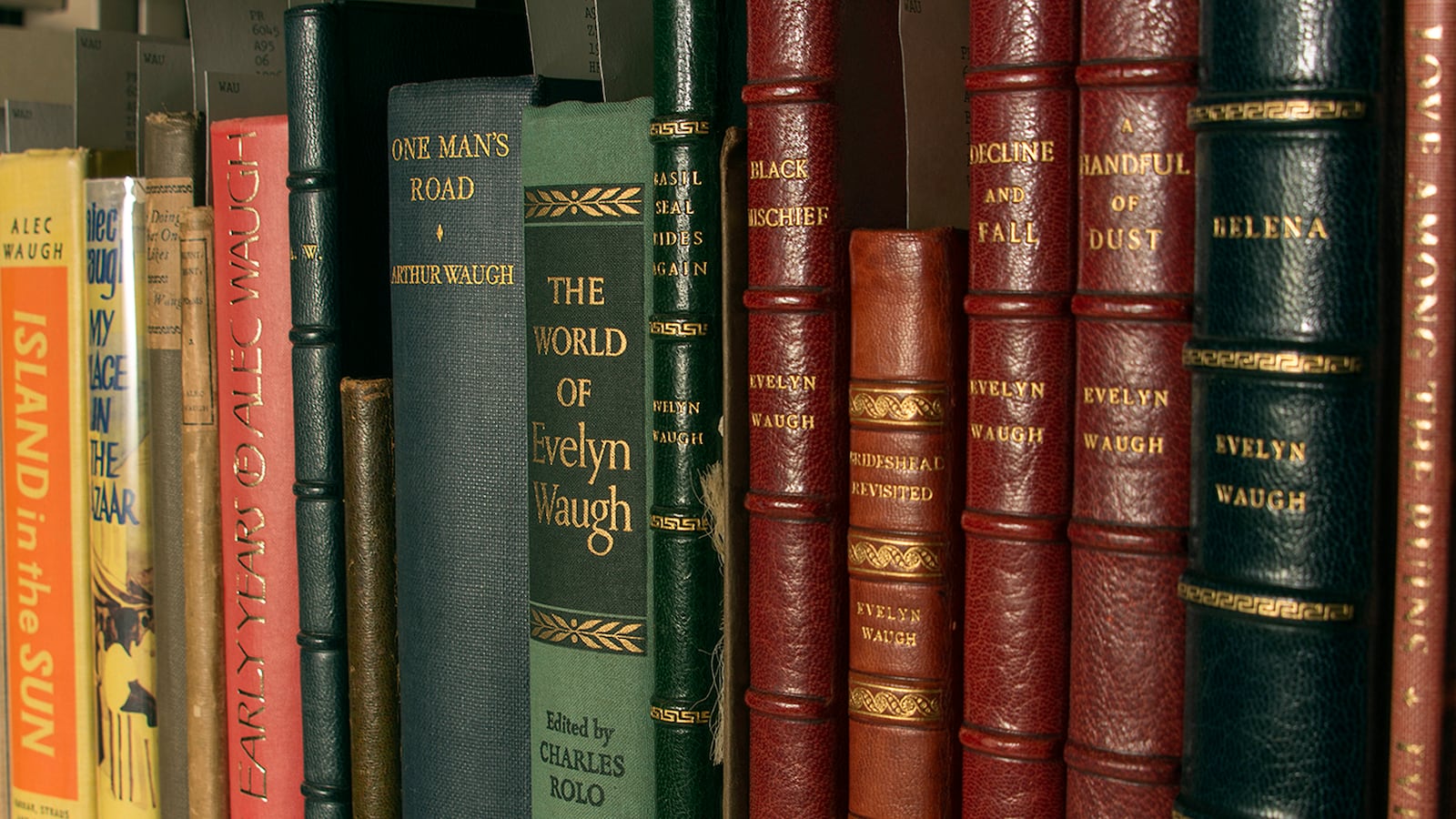

Until recently, nobody cared much about authors’ personal libraries. Not a single fully authenticated volume belonging to Shakespeare has survived, although a handful from the libraries of his contemporaries Ben Jonson and John Donne are still with us. The usual fate of a writer’s library was sale by auction, or worse, a dump on the curbside or into a bonfire by indifferent heirs. As a result, the contents of the libraries of Henry Fielding, Charles Dickens, and William Makepeace Thackeray are known only because of auction catalogs. Toward the end of the 19th century, however, collectors began to covet so-called association items, including books belonging to important personages. Later, large academic libraries began collecting literary archives, and sometimes the author’s own library in the bargain. The Harry Ransom Center, where I am associate director, owns more of these than any other institution; they include the books of Evelyn Waugh (an accomplished bibliophile), Ezra Pound, Anne Sexton, and scores of other writers. A couple of years ago, we acquired 300 annotated books that had once belonged to David Foster Wallace; these books became instantly popular, and for some of the fragile paperbacks we can now allow access only to digital copies.

Like Wallace’s curious fans, most of us are thrilled to hold a book that was once pored over, and perhaps even dog-eared or used as a filing cabinet, by a well-known writer. Scholars love to discover what writers read, and it’s even better to find written evidence, in the form of annotations, of their response. I can tell you that from the curator’s perspective, these libraries can be a mixed blessing. They typically occupy a great deal of precious space and cost a lot to catalog. Sometimes writers’ books languish in obscurity for decades before they come into their own. These days, hardly anyone is interested in investigating the reading tastes of the bestselling novelist Christopher Morley, whose archive and library are housed at the Ransom Center. But, as it happens, Morley knew everybody in literary New York in the early years of the 20th century, and so his library turned out to be a nearly inexhaustible mine for our exhibition on the Greenwich Village literati of his day.

A few years ago, a Yale graduate student lamented in the pages of The Boston Globe that books belonging to the experimental writer David Markson had been relegated to the shelves of the Strand Bookstore in New York. The unpleasant reality of bibliographic life is that dispersal is still the default fate for most writers’ libraries. The late novelist John Fowles, for example, accumulated a household full of books, many of them on the history and ecology of his beloved village, Lyme Regis, in Dorset. The library was so enormous that it was too large for any repository to digest and was therefore sold off over several years. If you are an admirer of Fowles’s work you can purchase one of the author’s signed, annotated books for less than the price of dinner.

On occasion a writer’s books are sent out into the world and somehow manage to cheat oblivion. Thirty years ago, a scholar tracked down some boxes of Mark Twain’s books, a few hours before they were sent to the landfill. The Ransom Center, which owns the bulk of Nancy Cunard’s papers, gained access this fall to a previously unknown cache of her books. The poet, publisher, and crusader for progressive causes died in 1965, leaving behind a boarded-up house in the south of France. Some of her books were purchased from her solicitor before the property was sold. The buyer was a professor and must have recognized their importance; nearly a half century later they arrived at their final home.

The 130 or so books are representative of her wide range of interests in social and political causes, as well as avant-garde literature and fine arts. Today, Cunard is best known as the compiler and publisher of Negro: An Anthology (1934). Negro had a stellar list of contributors, and its importance as a seminal document in the fight for racial equality is now widely recognized. Among the most significant books in the current acquisition are five from one contributor, the Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes, who earned her gratitude by allowing Cunard to publish several of his poems in the anthology without fee. In all, about 15 books are by contributors to Negro or relate to her work on it in some way.

Cunard’s other great cause of the 1930s was Spain; she worked tirelessly on behalf of the anti-Franco Republican forces and fell in love with Spanish culture. Later, she made numerous trips to Latin America. More than a few of the recently acquired books are by Spanish writers, members of the so-called Generation of 36. Warmly inscribed volumes, including one by Concha Mendez, poet and sometime mistress of Luis Buñuel, and the dramatist and poet Antonio Aparicio testify that her affection for Spain was reciprocated.

It is always particularly satisfying to discover books by a writer’s closest friends. In this case, there are two books inscribed by Janet Flanner, who, as “Genêt,” chronicled Parisian life for The New Yorker. Flanner has inscribed a couple of books, one of them to “darling Nancy, 1/3 of our tender trio” (the third member being Flanner’s lover Solita Solano).

Writers’ libraries are nearly always ancillary to their papers, although the books are capable of providing additional and sometimes unexpected insights into these figures’ lives and creative process. Items that belonged to writers have their own tale to tell.