In 2006, The Economist advocated a draft parliamentary law that would restrain the power of a single man, whose “twin roles as politician and media mogul” allowed him both to set public policy and to influence public opinion. The magazine was editorializing against its longtime enemy, former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, who then controlled the country’s most formidable political party and its most powerful media outlets, which, naturally, tended to approve of his leadership.

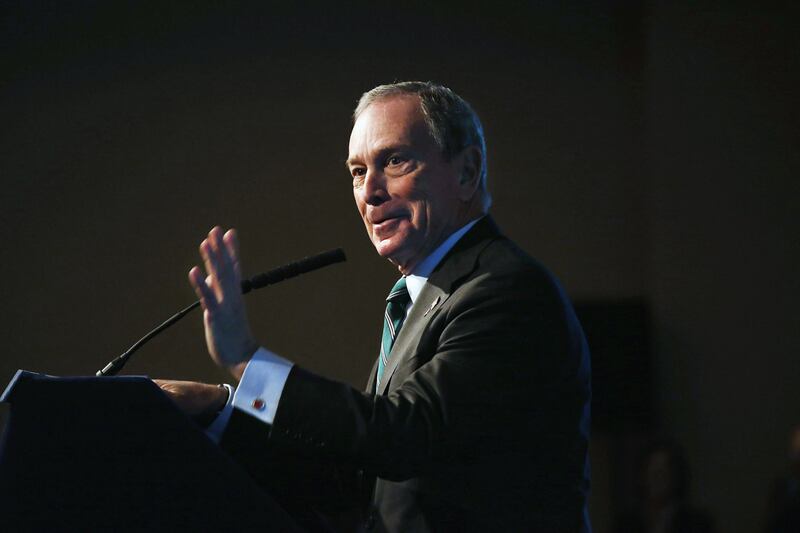

The Economist soon might have to contend with its own media mogul and politician, albeit a far different one from the disgraced Berlusconi. According to a report in The New York Times on Monday, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has repeatedly expressed interest in purchasing the Financial Times, the well-respected financial broadsheet. The deal also would secure a 50 percent stake in The Economist, though the magazine is editorially independent and contractually protected from the political whims of the FT’s current owners. That arrangement doesn’t seem like it would sit well with the billionaire media mogul, who moonlights as New York’s mayor and who reportedly “sneers” at newspapers as a business model.

“You don’t have control,” he said of The Economist, according to the Times. “Why would you want that?”

As The Atlantic pointed out, in many respects Bloomberg’s “stranglehold on financial news makes him more powerful than Rupert Murdoch.” The Australian mogul is the éminence grise of the media world, widely criticized for his properties’ undue influence on the political process. Yet Bloomberg, who controls his own vast media empire—and has openly disregarded his vow to step away from it while in office—has rarely been taken to task for his myriad conflicts of interest, despite having his own super PAC and flirting with presidential runs.

In Trump-ian fashion, Bloomberg has named each of his enterprises after himself, to reinforce the power of the brand that is Bloomberg. As he wrote in his 1997 business auto-hagiography, Bloomberg on Bloomberg: “it would be me and my name at risk. I would become the Colonel Sanders of financial information services … I was Bloomberg—Bloomberg was money—and money talked.”

He owns a business magazine (Bloomberg Businessweek), an “information service for professionals who interact with or are impacted by the Federal Government” (Bloomberg Government), a television network (Bloomberg Television), and now an opinion page (Bloomberg View). All of them pay journalists generous salaries subsidized by the hugely profitable Bloomberg terminal, which, for a hefty subscription fee, provides financial analysts with real-time market-data analysis.

While all of this has made Bloomberg obscenely wealthy, landing him at No. 10 on the annual Forbes list of richest Americans, it hasn’t satiated his desire for greater control of the news industry. The Times reports that Bloomberg had previously “commissioned a study to assess whether The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times or The Financial Times would potentially become available” for purchase. At the least, the endless rounds of stories about Bloomberg’s ambitions are a reason for reporters elsewhere not to go out of their way to bite the hand that could one day feed them.

And Bloomberg has a long history of commingling his interests as a businessman with his public role and ambitions. The year before he first ran for mayor, his charity doubled its giving and began redirecting it to New York institutions. His eponymous news company also opened a new division to cover the city. New Bloomberg News columnist Jonathan Capeheart, poached from the Daily News editorial board, moonlighted as Bloomberg’s “policy advisor and tutor, drilling him with flashcards, and introducing him to other journalists, and black and gay New Yorkers,” former New York Times City Hall bureau chief Joyce Purnick dryly noted in Mike Bloomberg: Money, Power, Politics.

Today, alongside his City Hall bully pulpit, Bloomberg also has the recently launched opinion website Bloomberg View. “In an age of celebrity, when everybody is marketing his or her own brand,” Bloomberg View opined with no evident irony in its inaugural editorial, “an unsigned opinion article seems old-fashioned.” The piece went on to note that the editors didn’t yet know their “general philosophy,” but they were surely “committed to transparency and tolerance, to nonpartisanship and intellectual honesty, to free markets and data-driven solutions to national and international problems—values embodied by Mike Bloomberg, the founder of Bloomberg LP.”

The editorial page, explained one of its founding editors, would offer “ideology-free, empirically-based editorial positions about the pressing issues of our time.” That just-the-facts-ma’am approach to opinion, however ridiculous, matches perfectly with Bloomberg’s personal brand as a political leader who’s bigger than politics. He’s a lifelong Democrat who became a Republican to run for mayor, and then an independent in hopes of launching a presidential run, and this tactical party-jumping is even painted as a mark of virtue.

While Bloomberg View offers a broad range of mainstream editorial voices, when addressing Bloomberg’s pet issues—like public health, immigration, gun control, and post-partisanship—it acts as a tribune of his views, in both its editorials and its signed columns. As one person who works for a Bloomberg news organization told The Daily Beast, Bloomberg’s “desires cast a very wide shadow on the Bloomberg empire,” especially with regard to opinion journalism.

In a Bloomberg View piece broadly supportive of the Bloomberg plan to ban large sodas in the city, Michael Kinsley cracked that “Bloomberg is the founder and majority owner of Bloomberg News’ parent, Bloomberg LP, and therefore my boss. In all likelihood, therefore, he is right about soft drinks and sugar, just as he is right about almost everything.” A grain of truth in every joke.

On Nov. 1, as New York City began its slow recovery from Hurricane Sandy’s devastation and just days before the presidential election, the mayor, who’d withheld his endorsement even as he’d teased the press with it, announced that he was backing President Obama, citing his more aggressive policies on climate change. “While the increase in extreme weather we have experienced in New York City and around the world may or may not be the result of it,” Bloomberg wrote (at Bloomberg View, of course), “the risk that it may be—given the devastation it is wreaking—should be enough to compel all elected leaders to take immediate action.” The endorsement’s byline attributed the column to “the editors.”

The same day, conveniently enough, Bloomberg Businessweek released its provocative cover story on Sandy, with a picture of flooded Manhattan and the stern headline “It’s Global Warming, Stupid.”

But Bloomberg pledged as a candidate in 2001 to step away from his business interests if elected, and signed a comprehensive 16-page decision from the Conflict of Interest Board after taking office in 2002. For years after that, he claimed to have ceded control of his company, even as it hired his deputy mayors and political allies. It was only after three plaintiffs in a federal lawsuit alleging gender discrimination at Bloomberg LP claimed in court filings that the mayor had discussed their case with employees at his company in 2007 that he changed his tune.

“I am the majority owner, and I’m absolutely entitled to talk to the senior people and am entitled to know what’s going on,” he said, contradicting earlier statements about his lack of involvement. “And I will continue to do that. I’ve been doing that since I became mayor.” Earlier the same week, he’d insisted that “I haven’t had anything to do with running it, or any discussions about their employment policies for a long time.”

While it’s doubtful that Bloomberg micromanages political messaging from his opinion website, it is nevertheless clear that its editors rarely cross wires with the boss—and that they don’t mind writing pieces that seem likely to please him. In one notable instance, columnist Jonathan Alter penned an attack on one of the mayor’s most prominent critics, New York University professor Diane Ravitch, who helped puncture Bloomberg’s claims of “historical” public-education progress. Alter called her “the leader” of “the forces of the status quo ... [o]bstructionists with a talent for caricature,” before the coup de grace: “[T]he education world’s very own Whittaker Chambers.” Nowhere did Alter mention that Ravitch had clashed, repeatedly and prominently, with the man who signed his checks, and under whose name the attack ran.

Last year, a source within Bloomberg told Forbes’ Jeff Bercovici that Bloomberg View had put some of its staffers at the offices of the Bloomberg Family Foundation, the mayor’s well-endowed charity run by Patti Harris, “enabl[ing] Mike to meet with them, talk to them, have influence over what they write.”

One Bloomberg employee told The Daily Beast that the mayor has “a desk” at the office but added that it might be related to his work with the foundation, which is across the street from his townhouse on the Upper East Side.

Harris, the powerful first deputy mayor, came to City Hall from Bloomberg LP and now also “volunteers” as the head of the Bloomberg Family Foundation, deciding who will and won’t receive hundreds of millions of the mayor’s private largesse. As one source put it to Purnick, Harris is “really deputy mayor for Mike. She would look after everything that touched on him, his life and his philanthropy.” The mayor’s super PAC Independence USA, run by Deputy Mayor Howard Wolfson, who took a leave from City Hall through the election to run it, also operates out of the building. The president of Bloomberg LP is former deputy mayor Dan Doctoroff—who was interviewed for the position by Bloomberg. “I’m thrilled to remain part of the Bloomberg family,” he said on taking the new job. And the list of deputy mayors and other employees crossing over, as well as operatives and politicians finding safe haven in the “Bloomberg family,” goes on.

Shortly after 9/11, New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani floated the idea of extending his mayoral term for three months, arguing that the state of emergency created by the World Trade Center would be compounded by a political transition. (Eleven years later, with Ground Zero still a construction site, it’s worth considering if the extension might have paid off.) The suggestion was met with furious denunciations that he was overturning the term limits voters had approved in 1993—and again in 1996. The city and state legislature shot the idea down.

By contrast, Bloomberg—at a loss for what to do after his ambitions for a 2008 presidential run petered out and faced with internal polling that showed New Yorkers would overwhelmingly oppose any bid to change the term-limit law—lined up the backing of the Times, Post, and Daily News by meeting privately with the owner of each paper to ensure they’d back his bid to avoid the public by having the City Council change the law. Only after his fellow press barons pledged that their editorial pages would back his play did he inform the public of his plan, claiming the financial crisis had made his leadership indispensable.

This Saturday, if Bloomberg goes off the grid for one of his regular weekends in Bermuda, perhaps he could discuss the frustrations of being both a mogul and a politician with his neighbor there—Silvio Berlusconi.